On the western edge of Mumbai, over a landscape of marshlands and mangroves, construction on an 18-mile-long coastal road snakes its way up out of the silt. The $3 billion development is one of India’s most ambitious infrastructure projects: a proposal to create land out of water, a highway on stilts over the Arabian Sea. An eight-lane freeway connecting Nariman Point in south Mumbai to Kandivali in the northern suburbs, this project will serve approximately 3% of the city’s population during a time when the country’s existing infrastructure is insufficient to manage basic needs, says anthropology Associate Professor Nikhil Anand of the School of Arts & Sciences. The coastal road is a land reclamation project where the city is draining water and making land, adds Anand. “This is precisely the opposite of what we should be doing right now,” he says. “The city is building the conditions for flood.”

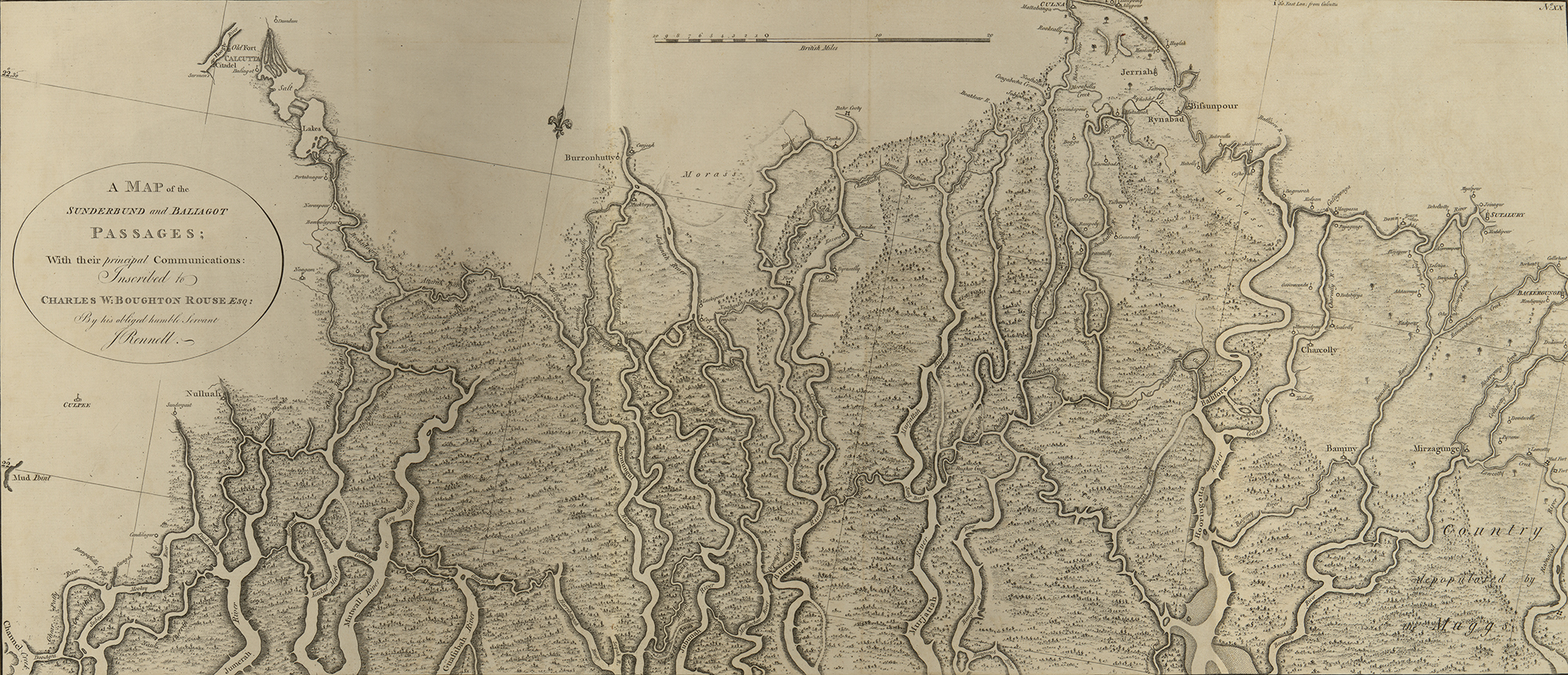

“The emergence of coastal cities built in estuaries where tide and freshwater meet is unique to a particular moment in colonial history when planners privileged land and marginalized the sea,” says Professor Anuradha Mathur of the Stuart Weitzman School of Design. “They imagined that they could control nature.”

That may no longer be the case. The 2020 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was one of the costliest on record, with cyclones Nisarga and Amphan making contact with the coast. This year, Cyclone Tauktae made landfall over the state of Gujarat on May 17 as it moved north after pummeling the state of Maharashta, where Mumbai is located. The storm killed at least 40 people; more are still missing. Approximately 12,500 people were evacuated from coastal areas during a time when the area is discussing lockdown measures. Maharashta currently leads India’s tally of COVID-19 infections.

Storm surges are only likely to increase as climate change progresses, says Mathur. “The Indian Ocean is the fastest-warming sea in the world,” agrees Anand. “With climate change, we ignore the sea at our own peril.”

Changing climate, static urban planning

Mumbai is one of the most vulnerable cities to climate change, Anand says. The intensifying monsoons that ensue as a result of warming seas have resulted in a 25% increase in heavy rain days in Mumbai. Yet development continues. In addition to the coastal road, the Navi Mumbai International Airport and the Mumbai Trans Harbor Sea Link are additional examples of the destruction and infill of seas and wetlands, Anand says.

India, he says, has endured a “double colonization,” that of South Asia by the British Empire, and that of humans over the environment. The second colonization has continued long after the British departed, Anand says.

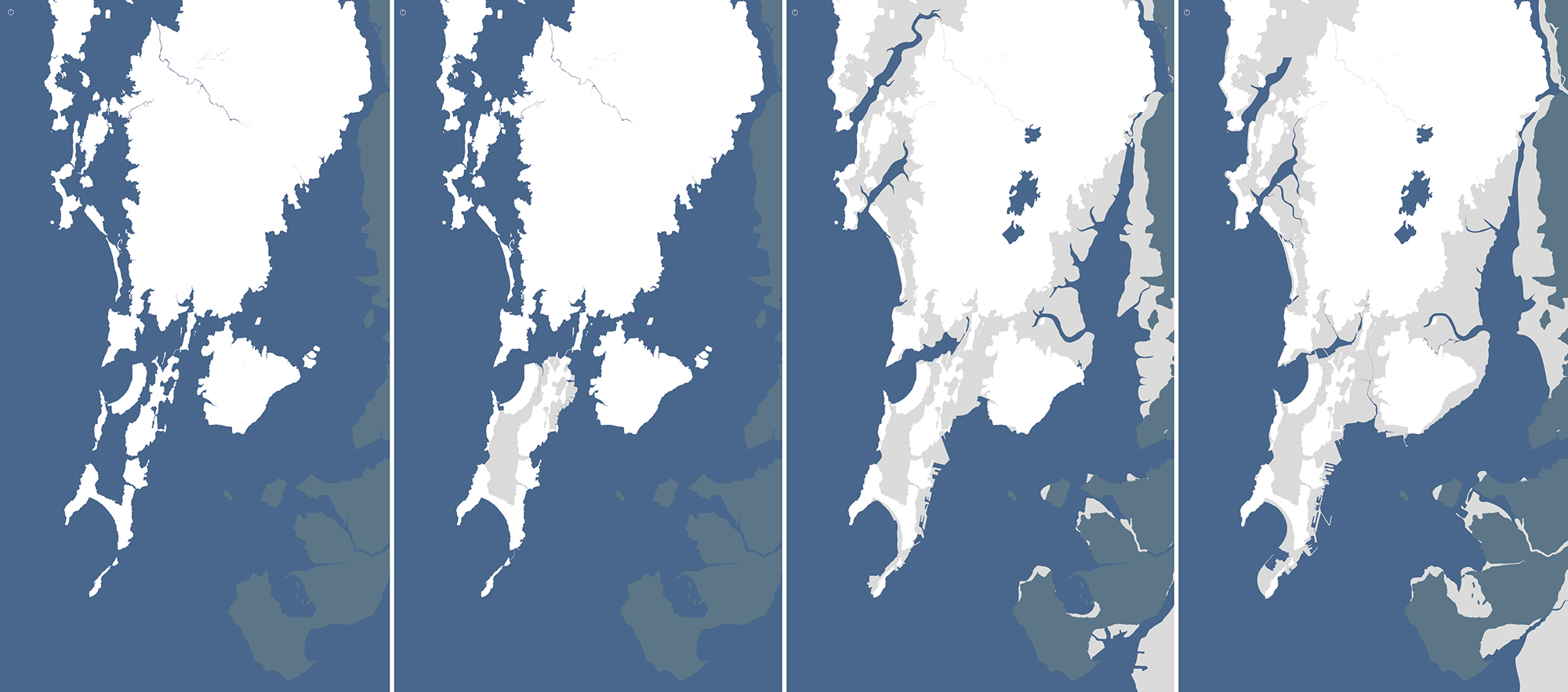

Cartography, finance, and law created the cities of Kolkata, Chennai, and Mumbai out of floodplains, wetlands, and intertidal regions, enabled by the work of surveyors and engineers, Anand says. Landfill not only makes dry land out of wetlands; it positions land against the sea. “Water is devalued real estate,” he says. “Further development doesn’t just make cities visible. It also makes the sea and water invisible.”

“The willful ignorance that is required to claim the sea as empty is not stupidity. It is not a lack of knowledge,” he says. “It is only by ignoring the existence of life in intertidal regions … that the city can tell a grand story of infrastructure and construction.”

When land is viewed as profit, marshland—which also serves as a buffer zone during storm surges—is seen as a liability, Anand says. “Ground that is sometimes dry and sometimes wet is seen as not valuable.” Capitalism builds on regimes of value, he says, so shifting towards a more environmentally friendly future is about “creating a new regime of value”—one that focuses on sustainability. “Look at solar panels,” Anand says. “There is money for things that people deem to be valuable.”

The current standard of urban planning in India does not value wetness, he says. Given the increasing toll of the cost of flood disasters and drought, “it’s only a matter of time before capitalists realize that it’s in their best interest.”

“What’s happening in India today is disaster after disaster,” Mathur says. “You look at the newspaper and you find that every city is flooding today, even places like Bengaluru that are not near any river or sea.” Typically, she says, city planners look at best practices, try to fix the problem, and then go on to confront the next flood. “Addressing the immediate problem just keeps us within that cycle,” she says. We don’t get to the foundation, the deeper questions of why we are where we are.”

Mumbai is a monsoon landscape, Anand says. Instead of fighting the elements, “what if you thought about working with them?” he asks. “We would have something to show the world.”

The monsoons are winds that come each year between July and September, Mathur says, and inhabit a whole season. India’s coastal cities that receive most of the rains during this time cycle between flood and drought, she says. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

“We haven’t developed our infrastructure to embrace the monsoons and we continue to work towards a model of dryness” that involves draining the city of water and eradicating wetness, says Mathur, an architect and landscape architect. As cities are synonymous with dryness, draining land is inherent to Indian urban planning. “What would it mean if we thought about holding wetness?” she asks. “Holding wetness in everything—in plants, in the air, in building materials, in infrastructures. It is a monsoon sensibility that has been largely lost.

“More and more, the trajectory of development and infrastructure has been such that we remove wetness from our environments, whether we are cutting down forests, paving our streets, or gathering drinking water,” Mathur adds. India inherited design templates from colonial practices, she says, and walls serving as barriers to hold back the sea and rivers are only temporary solutions. Draining water might work in elsewhere but is not appropriate for a monsoon landscape that has “been forced to behave like it was temperate,” she says. “In the long-term, we need other strategies.”

‘There is no water scarcity’

Anand’s 2017 book project, “Hydraulic City,” from Duke University Press, focused on water infrastructure, engineering, and the urban poor. Access to reliable, clean water continues to be an issue, he says.

Growing up in Mumbai, and again while working in Mumbai on this project, Anand was told, “as everyone has been told in Mumbai, again and again over the last 40, 50, 60, actually 100 years, that Mumbai has a water scarcity problem, that the city cannot distribute water to its population sufficiently because there simply isn’t enough. Which indeed, as anyone who has lived in western coastal monsoons in India knows, there is no water scarcity. To the contrary.”

Historically, India has held rain in a system of reservoirs and tanks. “It’s almost as simple as that,” says Mathur. “We held rain wherever it fell.” There is enough water for everybody in Mumbai, but the city and region do not hold it, she says: “We let the water just run.” Meanwhile, in times of drought, private citizens are told to collect rainwater in their individual households. Mathur says the entire region needs a systemic change to collect and hold rain.

In addition to rainfall, Mumbai is fed three and a half billion liters of water every day, piped in from the region’s reservoirs, which should be sufficient for 15-20 million inhabitants, Anand says. Mumbai’s water department has an annual operating surplus of approximately $300 million U.S. dollars, so funding is not an issue either, he says.

According to Anand, “water shortage is not about water, money, or tech.” In the everyday politics of distribution, some residents are viewed as deserving sufficient water and others not, he says. Yet the consequences of neglecting water infrastructure in Indian cities has been revealed during the pandemic. “Absent water and sanitation, how might people stay healthy?,” Anand asks. “How might public health be maintained?”

In addition to insufficient drinking water, Mumbai has also been hit with “garbage tides,” where the city is inundated with a backflow of trash and sewage, Anand says. Much of Mumbai sits at or under sea level, built on landfill, “as its residents are only too aware,” he says. “And everyone has noticed increasing regularity of unusual flooding events.”

Pollution, warming seas, algal blooms, and infrastructure construction along the shorelines— “together these processes are not just transforming the field [of design], but also the future of cities that are built on, or more accurately in, the seas around the world,” Anand says.

Climate planners and urban administrators address climate change in two ways, he says. The first is through mitigation, which includes reducing the production of carbon dioxide by de-incentivizing personal transportation vehicles, for example, and moving to fossil fuel free or less carbon-intensive modes of energy consumption.

The second is through adaptation, or altering behaviors or infrastructures in response to the impacts of climate change. It’s important to examine how climate change affects rain-fed irrigation systems and how humans can better inhabit an environment that experiences both intense rainfall as well as prolonged drought, Anand says. In order to manage the dry spells, India needs to think about “making cities more spongy, more resilient, more able to hold water,” he says.

Yet despite the evidence that planners and administrators in Indian cities see and recognize, “they’re not addressing the issue, either with mitigation, nor adaptation projects,” Anand says.

One of the questions that Anand asks in his research is why planners, whose job is to think about the future of habitation, are failing to act. It’s not that they “don’t believe in climate change; it’s just that they don’t act on that knowledge of climate change,” he says.

“Land thinking is insufficient to rethink the future of Indian cities,” Anand says. It is imperative that officials plan for cities in water before they are under water, he says. “In Mumbai, they are building a road to serve people in 2035. Why aren’t they making climate plans for people in 2035?”

Land vs. water

Mathur began thinking about wetness while working in the lower Mississippi landscape with her partner, Dilip da Cunha, adjunct professor at Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation. There in the “Big Muddy,” da Cunha and Mathur found that “flood was really a consequence of design,” Mathur says. She calls this “the incarceration of water.”

“You draw a line, water crosses it, and you say it’s a flood. We’re always trying to contain water,” Mathur says. Whether in a river, a coastline, a channel, water is the negative space between two lines, Mathur says. Da Cunha’s latest book, 2019’s “The Invention of Rivers” from Penn Press, has the thesis that rivers—what we assume to be a natural phenomenon—are in fact a culturally constructed product of human design dating back to ancient Greek cartography. Says Mathur, “one of the questions that we have been probing for a long time is: Where did this imagination of the line come from?” In drawing lines between water and land, humans have created the disaster of flooding. There is nothing natural about floods, she says.

“One of the most fundamental separations on the earth’s surface is the separation between land and water,” say da Cunha and Mathur, but there is a prior condition called wetness. “When you think about wetness, it becomes a non-dualistic pursuit,” they say. “Wetness opens up a radically new sensibility and paradigm for design.”

“Urban worlds are imagined and made possible through water,” Anand says, but “much of what we know of cities is through the imagination of cities as dry land.” Urban planning in India continues to reproduce this understanding of the dry, modern city, he says. Now, it is critical to innovate by learning from the environmental conditions and social knowledges that are situated in particular places, rather than following the model of Singapore or Shanghai, Anand says.

“The monsoon is and was a gift in India,” Mathur says. “Every time the monsoon came it was a time of joy, when temperatures went down. There’s music written on the monsoon; there’s poetry and stories. But more and more, we find that the monsoon arrives and the newspapers are just filled with stories of disaster.”

“And so our question was, how did the monsoon that was a gift, become an enemy?” Mathur asks. “And what have we done with our infrastructure that has taken us there?”

Cities have been caught between the sea and the monsoon, Mathur says. “A lot of my work with Dilip da Cunha has looked at other imaginaries that don’t look at these two things as enemies.”

Inhabited Sea

Mathur and Anand collaborate on Inhabited Sea, a trans-disciplinary and cross-continental project supported by the Provost’s India Research and Engagement Fund that seeks to reimagine the human relationship to water—and in doing so, the urban landscape. The project began, says Anand, “with a shared conviction that there is an urgent need to a shift to how we think about the environment.”

“The crisis confronting Indian cities is a crisis of the imagination,” says Anand. “The answer, we say, is to completely rethink and reimagine cities in wetness.”

Through Inhabited Sea, 22 participants in both India and the United States collaborate on eight projects to explore the question of what we might learn by thinking and working with and from people already living in wetness during uncertain times.

PlastiCity looks at the plastic in the Arabian Sea bordering Mumbai. This bi-continental team, consisting of Helen White and Ellie Kerns from Haverford College, Courtney Daub and Adwaita Banerjee of Penn, Siddarth Chitalia of the School of Environment and Architecture and Zulekha Sayed of CAMP, both located in Mumbai, looks at the flow of these Anthropocene byproducts and how they produce new habitats for those living in, on, and around the sea.

“The project started with me collecting plastics on the coastline,” says White, a chemical oceanographer. “We were thinking about how humans inhabit the oceans” as human refuse takes up residence in the natural environment, she says. “We see that some marine life that lives in those coastal cities systems can actually live on or live within those plastics,” White says.

Periwinkles are able to coexist with plastic and Shell binder worms that traditionally bind shells as a means to trap and eat microbes are collecting pieces of plastic instead, she says.

As a chemist, White was initially most curious about the chemical composition of this plastic to ascertain which products end up polluting the waterways. White found herself surprised and intrigued by the social studies of her collaborators, who brought to her attention the economy around collecting and trading plastics.

“Understanding the flows of plastics and how humans interact with them is a critical part of the story in Mumbai and globally,” White says. “What types of plastics do we want to be making and using, because we do need to have a pathway for them. It continues to ask the question, could we be doing something better?”

In “The Sea and the City,” Inhabited Sea collaborators Lalitha Kamath and Gopal Dubey of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences explore the idea of living with wetness through the experiences of the Kolis, Mumbai’s indigenous fishing community.

“The Koli community has practiced a form of artisanal fishing for centuries,” says Kamath. “This has enabled a form of knowing time and space through fishing practice that is attuned to different rhythms than those that are land-bound.” Koli fishers track the moon and tides to discover water rise and fall, she says, using a sense of time more tied to ecology than to a clock.

The fishers are attuned to the monsoon landscape as well, which shapes their fishing season and cultural practices, including Naarli Purinima, Kamath says. This festival is celebrated on the full moon day of the Hindu month of Shravan, typically in August, she says. An auspicious day for the community, Naarli Purinima marks the end of the monsoons and the beginning of the fishing season, says Kamath.

The Koli fishers’ “knowledge of Mumbai is one that’s entangled with the sea, assembled by centuries of collective living amidst rising and falling water levels,” says Kamath. The sea underlies their fishing practice and “has mediated their social and sacred relations,” she says. “Today, as climate change threatens to remake our world, we suggest that we can learn from the fishers’ knowledge and practice that’s founded on this entanglement of sea and city,” say Kamath and Dubey.

Anand’s project, “Urban Sea,” also looks at traditional fishing practices. The world consists of overlapping practices of different social groups, he says. “Everyone’s bringing something to the world and learning something from the world.” As a cultural anthropologist, Anand studies these attributes, noting how fishers negotiate gradients of wetness while working with different weather conditions at different times of the year.

Mumbai’s fishers are attuned to their environment and can predict floods by attending to the direction of the winds and the phases of the moon, which indicate high tides, he says. This way of knowing could be applied in other settings as well. “Government would be much improved if we took into account how sea level rise, moons, and tides matter in the everyday life of the city,” Anand says.

This community already organizes its livelihood and social world around pollution and climate change, Anand says. He looks to these practices to inform possibilities for Mumbai’s future.

‘A new imagination’

Mathur says the coastal road is part of an outdated way of thinking that believes that India has to look elsewhere for knowledge rather than paying attention to local intelligence and the particularities of place. In creating land from landfill, planners will disregard climate change and destroy mangrove habitats along with the working environment of thousands of Koli fishers who provide the city with sustenance, Anand says.

“In some ways, the road is a construction project that seeks to materialize the modern promise of speed,” he adds. “There is something so deeply symbolic about this. The road is flattening the city’s livelihoods and ecologies. Both at a local and global scale, it is producing the very threats of flooding and rising sea levels that will inundate the city in the near future.”

Despite all evidence to the contrary, humans imagine that we can continue to control nature. “That imagination is so durable,” Anand says. “That is why we need a new imagination.”

“As designers,” Mathur says, “we are always looking at these things, not just for documentation or critique, but to actually invent new possibilities. Can we open new ways of thinking today through how we image, imagine, and visualize?”