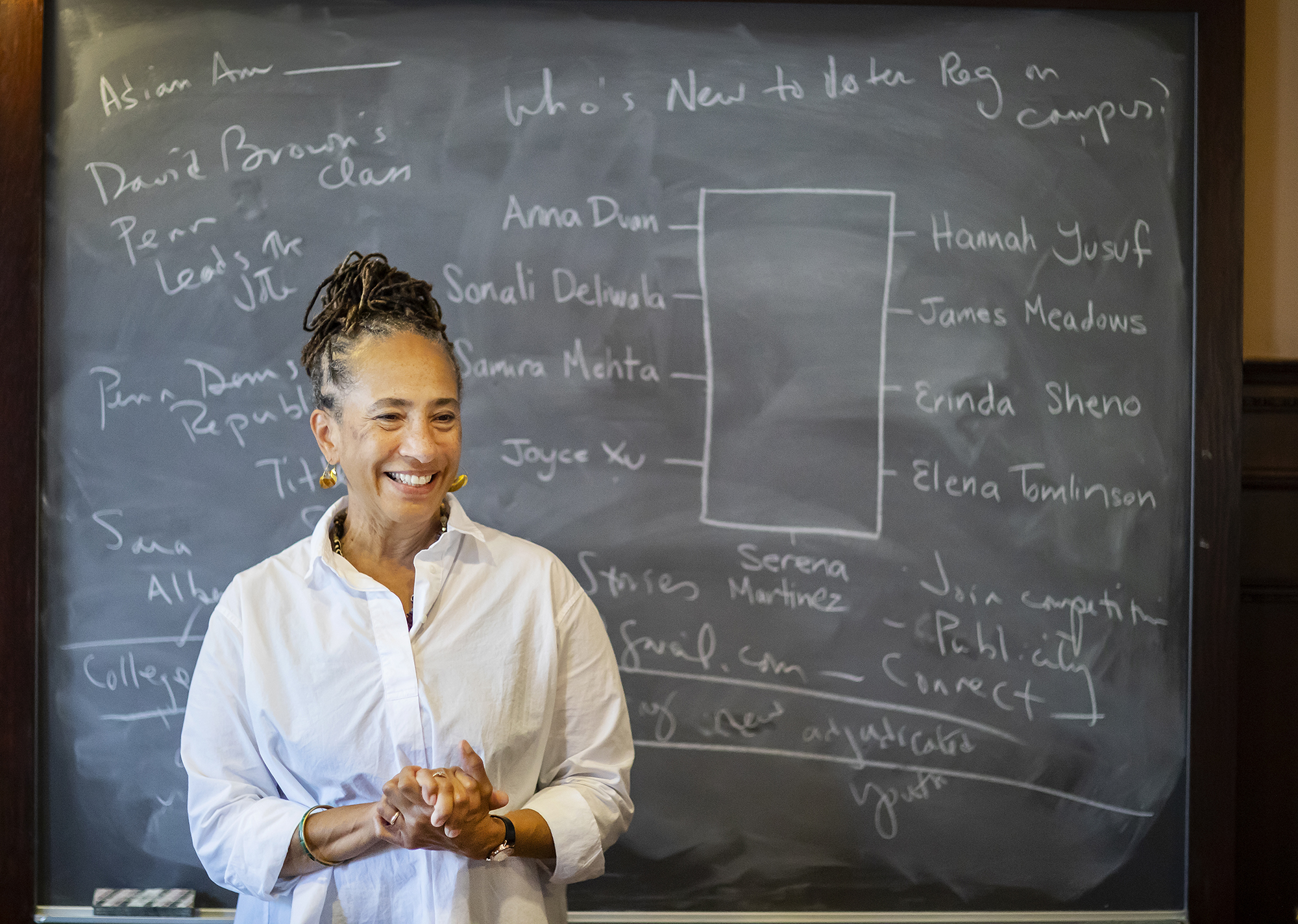

At 100 years old, Lorene Cary’s grandmother came to live with her. A senior lecturer in creative writing at Penn, Cary shifted gears overnight, from helping her grandmother manage, to being responsible for her care.

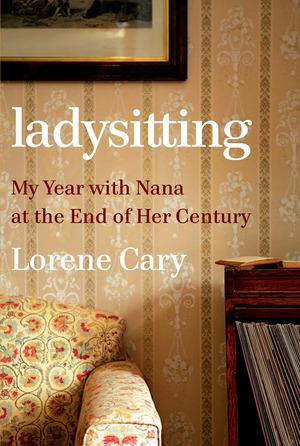

The story of their last year together is now a memoir, “Ladysitting: My Year with Nana at the End of Her Century,” that unveils an African-American family history going back five generations while at the same time describing details of daily life with Nana.

“It’s about class. It’s about South and North. It’s about immigrant cultures. And it’s about race, for sure,” Cary says. “These are the social subjects. But it’s also about the intense family experience of loss that happens when one member dies.”

It is also about the Philadelphia where Cary has spent her life, growing up in West Philadelphia, attending Penn as a student, working at Penn as a professor, and participating as a Penn parent.

Mostly, though, the story is about Rosalie Lorene Hagans Cary Jackson, who lived 101 years. In achingly personal detail, the narrative describes Cary’s earliest memories, from “a golden time” of playing in her Nana’s living room until the last difficult days as her grandmother’s body and mind were deteriorating.

No longer able to live alone in her home in New Jersey, and with no other plan in place, Cary’s grandmother was moved into the church rectory where Cary lived with her priest husband and one of their daughters, then in middle school. Cary arranged for a village of family, friends, and hired nurses to help care for her grandmother, including another daughter, care they called “ladysitting.”

The description of a middle-of-the-night crisis that was the beginning of the end starts with Jackson calling Cary for help when her legs get tangled in the bedrails, resulting in an exhausting struggle to put the complicated situation to rights. In frustration, Jackson asks if Cary wants her to die. Cary admits to the reader how badly at that moment she wanted to end the relentless work and what she describes as “the collapse of the Nana I’d known.”

“We know it’s coming, Nana.” I said it close to her, so that she could hear me without the constant unintended emphasis of shouting. “We both know that. But, listen, hey, you’re still here. I’m still here, how about a snack.”

The tender account of their “substantial low tea” in those early hours was the kernel that started the book project for Cary, she says in an interview. “I just had that one little bit, the sitting up and the snack, the tea,” she says, cupping her hands and gently blowing as if on a glowing coal to start a fire. “Often there is a little core, that is the ember.”

Attempting a challenging new move in a yoga class about four years ago opened her mind up to “writing her way” out of her grief. “That’s what we do in yoga, we make space in the body,” she writes in the book.

And writing is what Cary is all about. She graduated from Penn in 1978 with a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in English. She wrote and edited for national magazines before publishing her first book in 1991, “Black Ice,” also a memoir, about her experience as a scholarship student at St. Paul’s boarding school in New Hampshire, among the early classes that admitted girls.

Cary has been a professor at Penn since 1995, teaching writing and literature, often for academically based community service courses. She is the founder of the online publication, SafeKidsStories.com, which publishes writing by her students and other students in Philadelphia.

She is a celebrated author and social activist, the 2003 recipient of the city’s Philadelphia Award for her leadership in the arts communities. Her historical novel about a young female slave, “The Price of a Child,” was the first selected for the Free Library’s One Book, One Philadelphia project to promote reading and literacy. She has twice won Penn’s Provost Award for Teaching Excellence.

Cary is the founder of Art Sanctuary, a nonprofit to advance black art and artists, which figures prominently in “Ladysitting,” because she was juggling the planning of a 10th-anniversary celebration while caring for her grandmother just before her death in 2008.

It took Cary more than eight years, until 2016, before she took that yoga class and started blowing on that ember of a story and writing. She signed with publisher W.W. Norton & Company in 2017, and turned in the first draft in February of 2018.

While trying to finish that draft, she used her grandmother’s story to write a libretto for a mini-opera, “The Gospel According to Nana,” part of a three-year residency with the American Lyric Theater. Cary explains in a recent blog post that the libretto imagines a grandmother’s ghost haunting the writer’s computer to try to take control of the story. A portion of the opera will be performed at Kelly Writers House on Oct. 23.

The grandmother sings:

I’ll be gone, and

You’ll be free

To write anything

Your little heart desires.

“Writing this book says now she’s gone. I’ve admitted it,” Cary says in the interview. “But, in a way, my wrestling with the story, saying her name, singing it, keeps her memory alive.”

Cary will soon be packing to go to Europe to teach in the Penn in London summer abroad program, a class on writing for children. The itinerary includes attending live theater performances at least twice a week, which, she says, will act as a tutorial for her upcoming project, “My General Tubman.” The time-travel fantasy about Harriet Tubman will premiere at the Arden Theater in January, directed by Philadelphia playwright/actor/director James Ijames.

But at the moment Cary is traveling on a 10-city book tour to launch “Ladysitting.” The book is already getting attention, including an interview with Michel Martin on National Public Radio’s “All Things Considered.” And it is No. 1 on Oprah Magazine’s “10 Titles to Pick Up Now.”

Cary’s first public reading was at the Free Library of Philadelphia this month. Penn Today had a low tea and a conversation with Cary the next day.