“This lab is bananas,” said Chantelle Smith. “Most days I need headphones just to be able to focus on my work.”

She articulated this over the sound of toys rolling across the floor, robots singing and dancing, and students chattering about their latest discoveries in the Rehabilitation Robotics Lab at the Perelman School of Medicine. Normally, when things get this out of control, the seventh and eighth grade math and science teacher raises her voice and politely asks her students to quiet down.

But this summer, Chantelle Smith was no longer the teacher. She was the student.

That’s because Smith is one of 10 local middle school teachers who took part in this summer’s Research Experiences for Teachers (RET) program run by the GRASP Lab in the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Engineering and Applied Science.

The Penn program is part of a larger National Science Foundation (NSF) effort to get students interested in science and engineering at an early age. The NSF has established RET programs at more than 60 U.S. universities and colleges, where K-12 math and science teachers receive funding to complete research and develop curricula with the support of faculty and students. Penn’s RET teachers are paired with a variety of GRASP Lab members in different parts of the University, including the Rehabilitation Robotics Lab where Smith spent most of her summer.

At the time of her interview, Smith was in the final stages of her project exploring new applications for one of the lab’s more underutilized robots. When the sounds of tumbling blocks and shrieking robots finally subsided, Smith returned to explaining her summer research. “Have you heard of Cozmo?” she asked.

Cozmo is possibly the cutest robot you’ll ever meet. Big-eyed and pint-sized, the wheeled robot raced across a lab table according to Smith’s directions, drawing out the patterns of diamonds, circles, and squares.

“I want to use him as an assistive device for children with cerebral palsy,” she said as the robot accelerated away from her. “I’m exploring ways he can be programmed with accessible languages like Scratch. Cozmo’s cute for a reason. He’s supposed to encourage motivation and engagement. And I think he can help patients interact, especially kids who are non-verbal.”

“Look at us,” Smith laughed. “We’re even talking about Cozmo as if he’s someone we know.”

But that’s exactly the goal of the Rehabilitation Robotics Lab, which studies human-robot interaction to develop the most effective therapeutic robots for neurorehabilitation. By investigating the features of robots that make them more appealing — big eyes, a firm handshake, or some great dance moves — they can build a robot that’s better at its job of healing others.

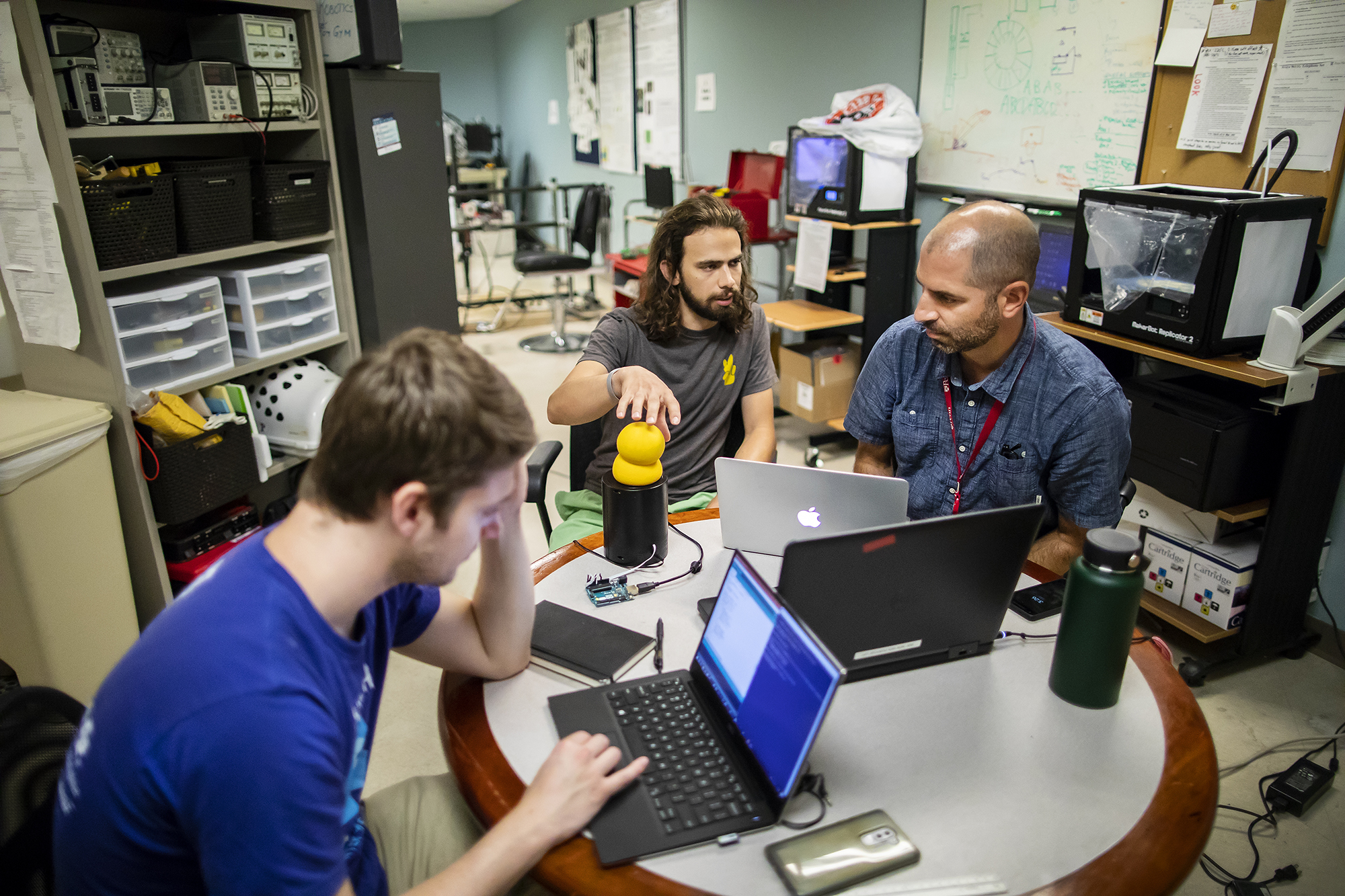

Smith’s RET colleague, sixth and seventh grade math teacher David Dimatties, was busy working on those dance moves. His project aimed to hack My Keepon, a socially assistive, dancing robot, to use as a motivational tool in physical therapy.

“I’m trying to hack this robot to get increased functionality to motivate and engage cerebral palsy patients,” he said, typing commands in Python on his laptop, “but it’s not working.”

He’d been trying to hack the bouncy yellow bot for over a week with no luck. Frustration can be a familiar feeling for the teachers in Penn’s RET program, where they’re often thrown into the deep end of Penn’s latest research.

“Nobody’s stuff ever works quite the way you expect it to,” noted Michael Sobrepera, Smith and Dimatties’ mentor and an Engineering Ph.D. student in the Rehabilitation Robotics Lab. “I think it’s really hard to understand how hard research is in the general scope until you really try to dig into it.”

“You’re doing things that by definition haven’t been done yet,” he continued. “Which means that every time you hit a roadblock, there’s not a YouTube video to watch or a book to read. You have to figure it out, because you’re going to be the one writing about it. And that’s challenging.”

The RET teachers found creative ways to navigate those roadblocks. As Smith packed up Cozmo and reviewed her work from the last few weeks, she remembered using lessons from the classroom to overcome RET’s challenges.

“The first three or four weeks were very intense,” Smith said. “I tend to freeze up when I’m under stress, and that’s what I did at first. But eventually I realized I couldn’t do that when I only had three weeks left.”

“And now that we’re coming to the end of the program, I’m realizing I won’t be able to finish all the work I wanted to do here. But I keep reminding myself to step back and experience it for what it is. When my students are struggling in class, I always remind them to try and succeed in another area. And that’s what I’m trying to do now. I’m trying to succeed where I can.”

The goal, though, isn’t to crush these teachers’ spirits, Sobrepera said. He hopes the intensity of the experience will make them better teachers.

“Most of these teachers have been teaching in their classrooms for many years,” Sobrepera said. “They’re very, very fluent in the material they teach. Then they come here, and we beat them up.”

“Suddenly they understand that being asked to execute in all these different ways without any knowledge is painful, and emotionally draining,” he continued. “That mirrors the emotionally draining experiences that their students have all been going through, and hopefully that allows them to go back and address those problems in the classroom. It shows them how to empathize with these students to make the experience better. That’s intense, right?”

It is, but Penn’s support of these local teachers will continue well after the RET program is over. Michelle Johnson, Assistant Professor of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Perelman, Assistant Professor of Bioengineering at Penn Engineering, and director of the Robotic Rehabilitation Lab, oversaw their work in her lab and plans to keep in touch.

“I feel like once the summer ends, it’s not the end,” Johnson said. “Here, they’ll have an opportunity to continue to engage with us, and for us to continue to engage with them and their students. And maybe the projects they start now will lead to significant discoveries in the future.”

This story, written by Emily Schalk, originally appeared on the Penn Engineering blog.