To teach about the Holocaust is to confront human beings in their most evil form. Scholars who teach about the tragedy retell and relate accounts of ungodly cruelty and indescribable misery, agony, and pain.

Teaching the Holocaust can be distressing to one’s soul. Not some long ago, far off catastrophe solely chronicled by history, it lives with us today, present in current affairs and a part of Jewish life. There are people walking the Earth right now who lived it, breathed it, endured it, and miraculously survived. Their pain is a lived pain, their suffering a firsthand horror.

Courses concerning the Holocaust are offered across Penn, scattered throughout the University. They are taught by survivors and the children of survivors, individuals with a personal connection, and researchers with an academic interest.

The study of the Holocaust is as interdisciplinary as Penn, spanning several fields, including literature, language, the law, history, science, medicine, ethics, and film.

For 31 years, Al Filreis, the Kelly Family Professor of English in the School of Arts & Sciences and faculty director of Kelly Writers House, has taught the undergraduate course “Representations of the Holocaust.”

He was moved to teach about the Holocaust in memory of his relatives who died in Poland, and was inspired by his undergraduate mentor.

While a student at Colgate University, he took a course taught by Holocaust scholar Terrence Des Pres. De Pres died young, in his late 40s, and Filreis said he gave him the course as a legacy.

“One of his main ideas about teaching is that teaching the Holocaust is as much of an obligation as bearing witness, that teaching is a kind of bearing witness,” he says. “He always talked about how you don’t want to be the person who breaks the link in the chain of witness, so I felt an obligation to that message.”

Filreis, also director of the Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing, says during the course of its three decades, the class has evolved to include more testimony, witness, and memory, and makes great use of video testimony.

“I think video testimony is really powerful in a way that disarms people, especially young people,” he says. “I think students respond to the seeming directness of a video testimony; there is a person and this person is speaking, this person is looking at me, I am making a connection, this person could be sitting next to me on the bus.”

Filreis has his students watch Claude Lanzmann’s “Shoah,” a nine-and-a-half hour documentary filled with testimony from survivors and witnesses, which Filreis calls “the best film I have seen about the Holocaust.”

Students who sign up for the course come from all across the University. When Filreis first started teaching it, he says many students had firsthand knowledge of the trauma.

“Now, of course, those people are few and far between,” he says.

The class begins in one of two ways. Students either read a memoir of a man who escaped from the Nazis as a child and hid in the forests of Europe for three years, or watch Steven Spielberg’s film “Schindler’s List” and discuss why the beauty of the film, a multiple Academy Award-winner, may be inappropriate.

The memoir, Filreis says, is a great way to start because the students can relate to the young boy.

“They’re 19 or 20 years old and they can identify fairly recently with the feeling of dependency and the fear of a child lost,” he says.

The primary focus of the course is addressing problems of representations of the Holocaust. When describing the tragedy, Filreis says a basic dilemma emerges.

It is an event too enormous, too deep, too problematic, too painful, and too traumatic to describe, yet there is a need to describe it to those who did not see it, with knowledge that words will fail to convey the enormity of the depth and pain.

“Is it impossible to describe, but there is an obligation to describe,” Filreis say. “I want my students to understand that dilemma so that we never take for granted the struggle that anyone who has seen trauma—whether it’s the trauma of mass murder, or the trauma of the sudden loss of a parent, or the trauma of a giant catastrophe—we should never take for granted how hard it is to represent that.”

Beth S. Wenger, the Moritz and Josephine Berg Chair of the Department of History in the School of Arts & Sciences, teaches about the Holocaust in a variety of different classes and in many distinct contexts.

Her “Rereading the Holocaust” course is an undergraduate seminar devoted to the study of Holocaust memory—how the event came to be understood and remembered.

“It traces a time when the Holocaust was not yet established in popular memory as a discrete event separate from the war to a time today when Holocaust consciousness is ubiquitous and, in fact, is often used as a metaphor for describing other mass genocides,” Wenger says.

Starting in the post-war period in 1945, the first part of the course helps students grasp how the Holocaust first came to be understood as a historical event, and how the term emerged to describe the attempted extermination of European Jews during World War II.

Wenger begins the course by asking students, who come from diverse religious and ethnic backgrounds, to recall their first memory of learning about the Holocaust, and what images flash through their minds when she says the word.

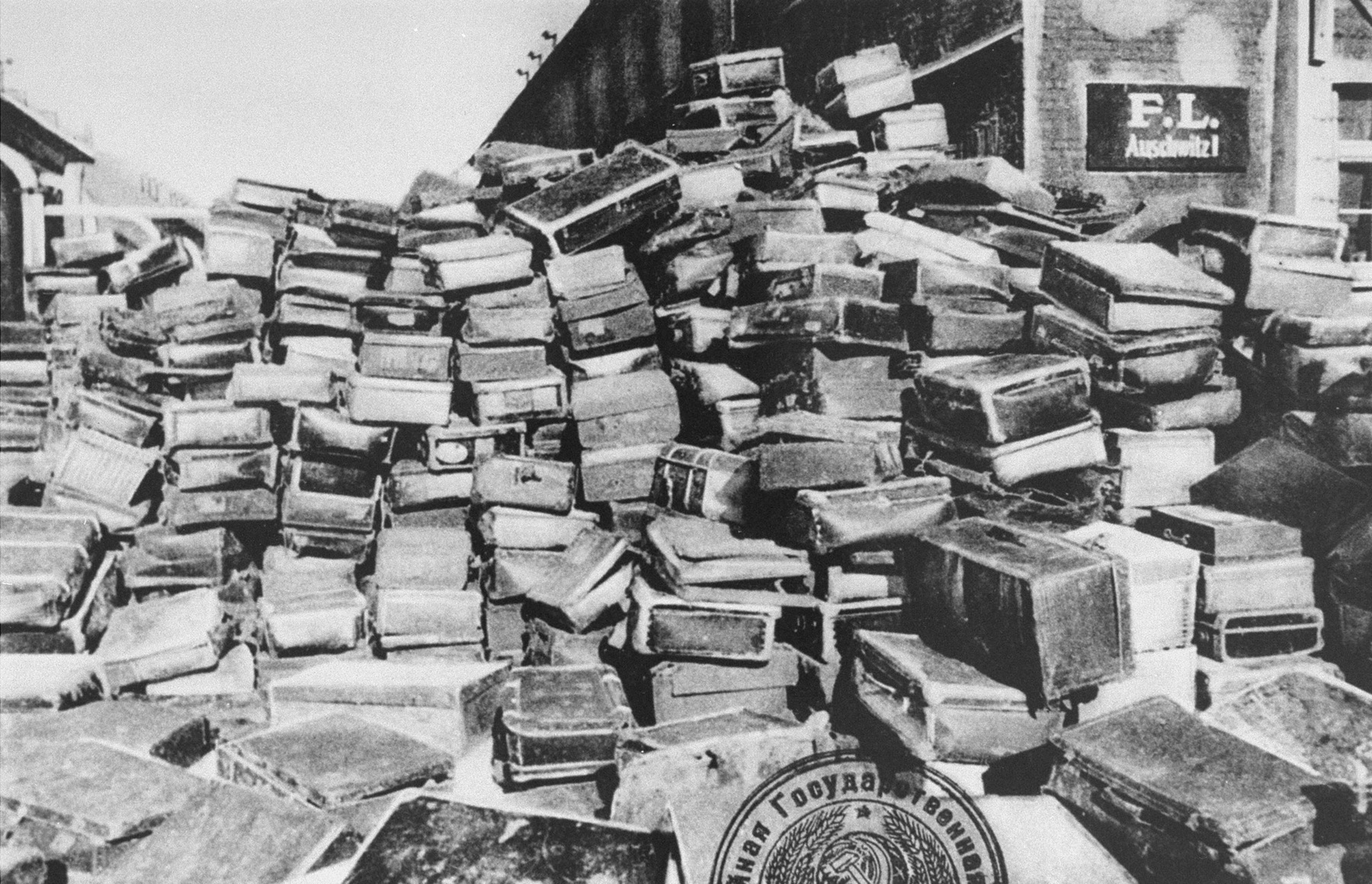

Largely, students mention books, films, images, and footage of death camp survivors and victims, visual impressions that most people in the 1940s and 1950s—the subjects of the first part of the course—had never seen.

“As I point out to them, they play a loop in their minds of all that archival film and footage that they’ve seen,” Wenger says. “I try to get students to reflect on the fact that they live in a moment where they’re saturated with Holocaust memory, but that was not always the case. We try to trace how the understanding of what eventually became the Holocaust unfolded over the course of several decades.”

The latter part of the course focuses on the ways Holocaust memory has been constructed in various national contexts, and through monuments, memorials, museums, and popular writing.

Wenger also teaches about the Holocaust in her course “Jews in the Modern World,” which traces the history of the Jewish people from 1750 to the present.

“One reason it’s important to me to treat the Holocaust in a survey of modern Jewish history is so that students can understand the event in proper historical context,” she says. “The Holocaust must be situated in the context of modern European history.

“Obviously the Holocaust is a crucial part of modern Jewish history,” she continues. “It changes the entire course of Jewish history, and the map of the Jewish world. It not only alters demographics and population centers, but influences the very shape of Jewish culture to this day.”

In her survey of American Jewish history, Wenger discusses American and Jewish American responses to the Holocaust, and what the United States did and did not do as a nation, what really could have been done, and to what extent Americans knew or grasped the nature of the Nazi plan.

Wenger says teaching about the Holocaust is always difficult, and she’ll never be unmoved by the subject.

“I would never want to arrive at a place where I feel that I teach the Holocaust the same way that I teach, for example, the establishment of a law or the history of a diplomatic treaty,” she says. “I try to do justice to the massive loss of the Holocaust by refusing to teach it as something that can be understood through slogans and trite conclusions. It must be taught in all its complexity.”

Born in Haifa, Israel, Nili Gold, an associate professor of modern Hebrew language and literature in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations, teaches “Holocaust in Hebrew and Israeli Literature and Film in Translation.”

The course concentrates on Israeli culture and how Israelis dealt with the trauma of the Holocaust as reflected in Hebrew and Israeli writings and cinema.

Around 30 students are currently enrolled; Gold says seven or eight have some connection to the Holocaust through relatives or family friends.

The class moves chronologically, beginning with writings by first generation survivors and witnesses, such as Israeli novelist Aharon Appelfeld, then slowly progresses to second generation literature, such as Amir Guttfreund’s novel “Our Holocaust,” and concluding with third generation literature.

“I teach quite a bit of poetry because I find that, especially on such a difficult topic, poetry is sometimes more powerful because it is suggestive,” Gold says, “because it doesn’t tell you everything, and it leaves much more to the imagination or interpretation.”

Several genres of Israeli documentaries and feature films are screened for the class, including “Because of That War,” a Hebrew-language documentary by the children of Holocaust survivors. Gold also shows the French film “Au Revoir Les Enfants” (“Goodbye, Children”), based on a true story of a boy who was hiding in a monastery and captured by the Nazis, and the American film “Exodus,” about the founding of Israel.

Gold says her main interest is the role of the Holocaust in the Israeli context. She says the Holocaust has a different meaning to the children or grandchildren of American survivors than it does to the descendants of survivors in Israel, where survivors and their offspring make up almost half the country.

“There’s a notion that if there were an Israel back then, the Holocaust would not have happened,” Gold says. “[Survivors and victims of the Holocaust] would have had a place to go to.”

Through lectures and literature, Gold discusses with students the mystery that surrounded the Holocaust in the post-war years, which stemmed from survivor’s silence about the terrors they endured.

“My own father was a survivor and I didn’t know about it,” she says. “He died when I was 10 and I had no idea what happened to him until I was older and my mother told me.”

When Israel was established in 1948, Gold says there was an investment by its leaders in convincing the population not to dwell on the tragedy of the Holocaust, lest they be consumed by the pain and the new country unable to survive.

“It took a while for the country, as a country, to say to itself, ‘Wait a minute, we have to remember,’” Gold says. Israelis began to open up about their suffering after the trial of Adolf Eichmann in 1961, but did not begin talking about it comprehensively until the 1980s.

Because she finds it emotionally draining, Gold does not teach “Holocaust in Hebrew and Israeli Literature and Film in Translation” very often.

“It’s very raw even though it’s an old story,” she says. “It’s a part of who I am in terms of my own family, but also, as an Israeli, I had friends whose mothers had a number on their arm. It’s very intimate. I’m not talking about strangers. I’m talking about myself in some ways.”

This semester is the third time she has taught the class, which she is teaching in English. She taught it once in Hebrew but says she will never do so again.

“In Hebrew, it was harder for me,” she says. “Because Hebrew is my native tongue, to speak about it in my native tongue—to actually talk about it and read the words in the language in which they were written, not in a translation—makes it more difficult. It some ways, the translation is like a shield. The translation defends me.”

Adolph Hitler did not murder 6 million Jews all by himself. He was aided by a barbaric military, and tens of millions of civilian bystanders who were in no way innocent.

Called to help make certain that an atrocity like the Holocaust never occurs again, Matthew Survis, a senior Philosophy, Politics, and Economics major, is promoting a society of “upstanders” armed to confront injustice in everyday life, wherever they see it.

Survis’ Upstander Initiative is an education platform for high school students designed to promote positive behavioral change. The program uses the lessons of the Holocaust as a launching pad to promote social awareness and action, and discusses how the horrific event can be relevant to the complex social issues teens face today.

Survis founded the program in 2008 when he was in eighth grade. After his bar mitzvah, he was involved with a program that paired seventh grade students with Holocaust survivors. He was paired with survivor Marsha Kruezman, who told him her story—and Survis says it was his responsibility to share it with someone else.

“I became really close with Marsha,” he says. “She gave me the charge to ensure future generations never forget the Holocaust.” He took her words to heart and researched and wrote the curriculum for the initiative, which he taught throughout high school in New Jersey.

Survis brought the program with him to Philadelphia, where it currently operates in five high schools: First Philadelphia Preparatory Charter School, Constitution High School, Northeast High School, Boys Latin Charter School, and Freire Charter High School. By the end of the semester, he says it will have reached 1,000 students.

The Upstander Initiative leverages a peer-to-peer model to help students identify problems they see in their communities, and what they can do to solve them.

“What we really try to focus on is the notion of empowerment,” Survis says. “We want to give [students] not only the knowledge that they’re capable of solving these problems, but the tools to actually do so.”

The program’s core school model has Penn students trained in the curriculum branch out into the high schools. The branch school model trains student leaders at the high schools, who then teach the younger students. Survis says the initiative works in partnership with the schools, and builds its curriculum into the existing lesson plan.

The core model consists of four sessions—usually four Fridays in a row. Students are given historical background information about the Holocaust during the first session in order to give them a common base.

“We really focus on the idea of ‘How did this happen?’ because that’s the most relevant for them,” Survis says, “to be able to take these lessons and learn from them to make them relevant today.”

The second session’s individual action component requires students to read diary entries of teenage Holocaust victims, and also from a German civil servant.

“We often have them, before the second session, write about a time they were scared as a homework assignment so that they can sort of put themselves in those victims’ shoes,” Survis says.

For the third session, through a partnership with the Holocaust Awareness Museum and Education Center in Philadelphia, a Holocaust survivor visits the class. The fourth session addresses how students can catalyze behavioral change.

Survis says the third session is usually the most powerful.

“Students come up after and want to touch the survivor and takes pictures with her or him,” he says. “I always get feedback that that is the moment that really clicks.”

In 2015, the USC Shoah Foundation awarded the Rutman Teaching Fellowship to Liliane Weissberg, the Christopher H. Browne Distinguished Professor in the School of Arts & Sciences. The fellowship is presented annually by the Foundation to a Penn faculty member to teach about the Holocaust.

Last semester, Weissberg, also a professor of German and comparative literature in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, taught the course “Witnessing, Remembering, and Writing the Holocaust.” A professor at Penn since 1989, she says she had not dared to teach such a course before last spring.

The daughter of Holocaust survivors, Weissberg grew up in Frankfurt, Germany, following the Second World War and saw firsthand the suffering of its small Jewish community and the unease of living in the country of their former oppressors. Most of the population came from displaced persons camps or moved to Germany after the war, and were “marked by the war in many ways.”

“The survivors survived not intact,” she says.

Growing up, Weissberg’s parents did not allow her to be alone on the street for fear that she would be taken, and she had to call home several times a day just to report that she was alive and well. Early in her youth, it was her task to care for her parents, to act as both child and parent in one.

“This is all very natural for people in my generation,” she says.

For these reasons, she needed to work through her own family history before being able to teach a course on the Holocaust.

Weissberg says she changed her mind for two reasons: Her strong engagement with psychoanalytic theory and her experiences teaching a graduate course on trauma.

“Increasingly, there was material here and there that I just had to discuss that related to the Holocaust, so I came to a point where I thought, ‘I’m ready,’” she says. “And when I decided to teach it, I also decided that I had to teach it because in some ways I was not only conveying a topic, but I was also a secondary witness. It became for me an ethical issue. I wanted to tell students what they may not be aware of or know.”

At its core, “Witnessing, Remembering, and Writing the Holocaust” asks questions about witnessing, about how the world found out what happened, and how people revealed what transpired. Weissberg says the main emphasis was on how witness reports taken after the war were conveyed, or “how we know what we know.”

The lecture course opened by considering footage filmed by the Russian and American liberators of the concentration camps, and the differences in how they described what they saw. The class continued by having students listen to the first voices of the victims from 1946.

In addition, students read historical accounts, memoirs, and novels, and viewed a collection of documentary and fiction films, including “Schindler’s List”—during her time in Germany, Weissberg knew Oskar Schindler well—and Claude Lanzmann’s “Shoah.”

The course also included material from the David Boder Voices of the Holocaust audio archive, the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies at Yale University, and the Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive, which has been made digitally available to Penn.

Students enrolled in the course came from myriad backgrounds, ages, and experiences, including undergraduates, graduate students, exchange students, and around a dozen senior associates.

“Many of the senior associates came out of their personal experiences,” Weissberg says. “Not that they were necessarily the children of survivors or child survivors, but because their neighbors were, or they heard about it, and they lived closer to the time.”

Weissberg says teaching the course was an extraordinary experience, but also the most taxing course she has ever taught.

“I certainly want to do it again, although it is not the kind of regular course that I can teach very often,” she says. “So maybe in a couple of years or so.”

This story originally ran in the Nov. 17, 2016 edition of the Penn Current.