While art outlines were once limited to paper sketches and etchings in the memory banks, today’s digital technology has fundamentally changed what’s possible for creating art—both process and product.

Or, so goes the theory behind the work of the Civic Portal project.

The project team, organized to reimagine public art and examine the possibilities of digital technology, is made up curators from the Monument Lab, as well as folks from PennDesign, Penn Libraries, and The Sachs Program for Arts Innovation. This summer, the team, along with 11 others from around the country, received a $50,000 grant from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation to research and test new technologies that drive engagement in the arts.

“We’ve worked with technology throughout our body of work with Monument Lab, but decided in the past to put technology on the back end for our research process. Rather than having an app or augmented reality for collection, we used pieces of paper, and Sharpies and clipboards for gathering public proposals, and the last step is uploading and compiling them with technology,” says Paul Farber, a PennDesign lecturer and artistic director of Monument Lab, who leads the curatorial team beside Fine Arts Department Chair Ken Lum. “This is an attempt to put [technology] on the front end, and see how our process evolves.”

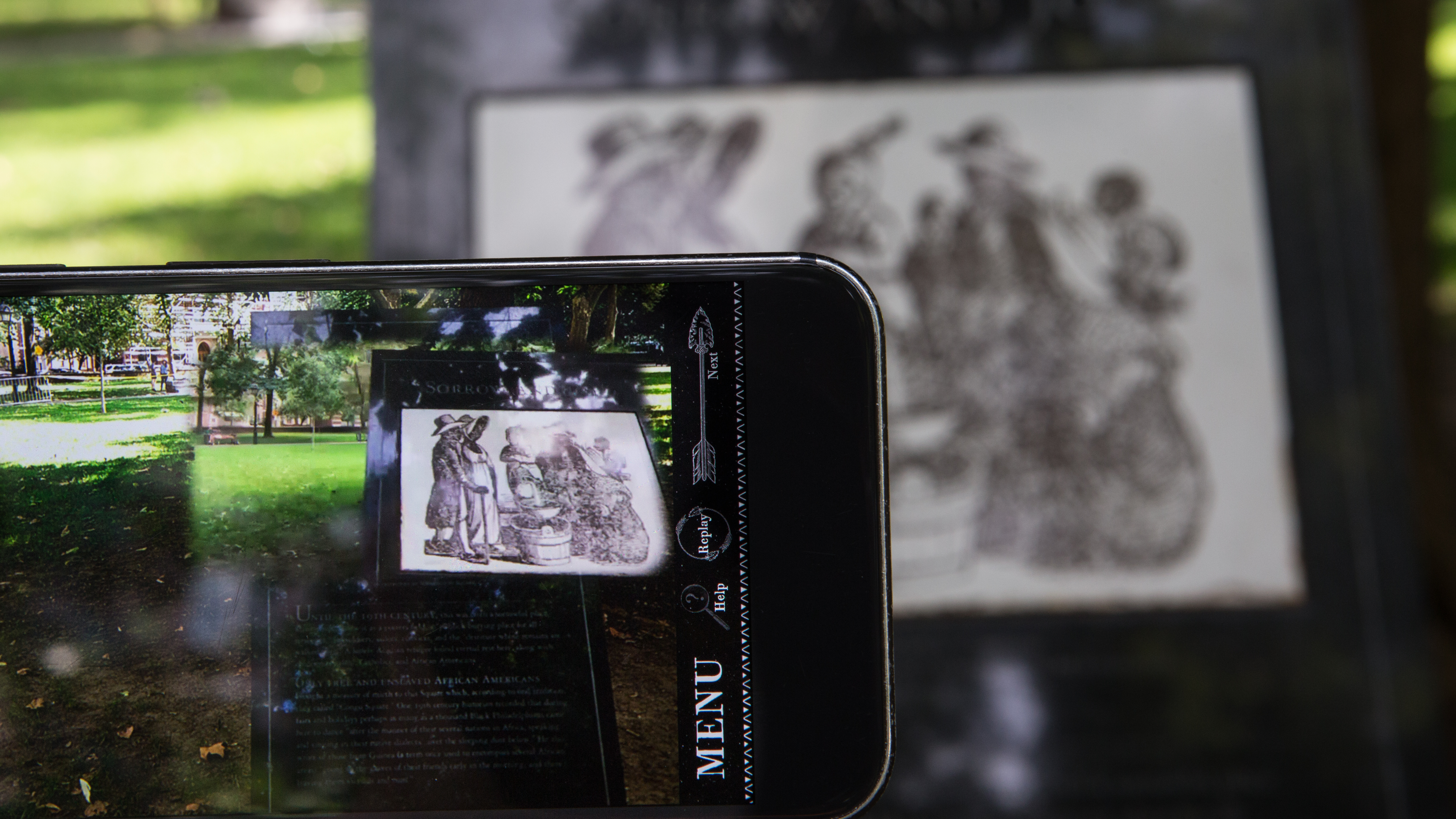

The project is in the early stages of a yearlong development process, but, in short, it is an effort to imagine and prototype an app that uses augmented reality as an accessible means to interact with conceptual designs for public monuments. The idea is to allow diverse input on how a monument might be improved or altered by offering a digital, space-triggered model that’s conducive to collecting feedback and dialogue.

“We’re imagining what goes on next, thinking about digital technology not just as a final answer, but another way to yield a conversation that is robust and inclusive,” Farber says.

The tool will be built by Venturi Labs, a Penn-affiliated, incubator-like company led by Stephen Lane, a professor of practice and director of the Computer Graphics and Game Technology Master’s Program in the School of Engineering and Applied Science.

While ideas are still flowing about what the end tool will do and look like, Lane says the general goal is to emphasize the capacity for community input.

“The idea is to have user engagement in terms of comments and feedback, and how it will affect the design of the monument,” he says.

In the past, Farber says, prototyping monuments meant literal constructions—for example, pop-up monumental installations in the courtyard of Philadelphia City Hall as part of past Monument Lab exhibitions, including 2017’s citywide project presented with Mural Arts Philadelphia. It also included the gathering method for paper proposals, that yielded over 4,500 contributions last fall from public participants, using a system designed with collaborators from Penn Libraries and the Price Lab for Digital Humanities. With digital technology, a prototype could be brought to life in a space—accessible only upon entering that site—through augmented reality, with room for community edits.

“In this case, a monument can be ripe for experimentation,” Farber says. “I think the key here is there’s a relationship between proposing monuments and public arts, and commenting and expanding the range of ideas. Even if you don’t have a deep design background, you still have something to offer and say.”

Put in context of today’s culture, Farber says the tool also has potential to invite dialogue over the growing problem of spaces left empty by controversial monuments.

“After the prototype phase, another example of how this could be used in the longer-term is for re-imagining empty pedestals in cities around the country that have deemed particular monuments as problematic, including those that have racist, sexist, and other exclusionary histories,” he says.

It’s an ambitious project with potential to reimagine the making and considerations of public art.

“Our hope,” Farber says, “is that we can help fuel not just a longer-term goal of working on existing monuments, to adapt or evolve them, but other municipal and public art processes that regularly are trying to experiment with and address issues in public spaces.”