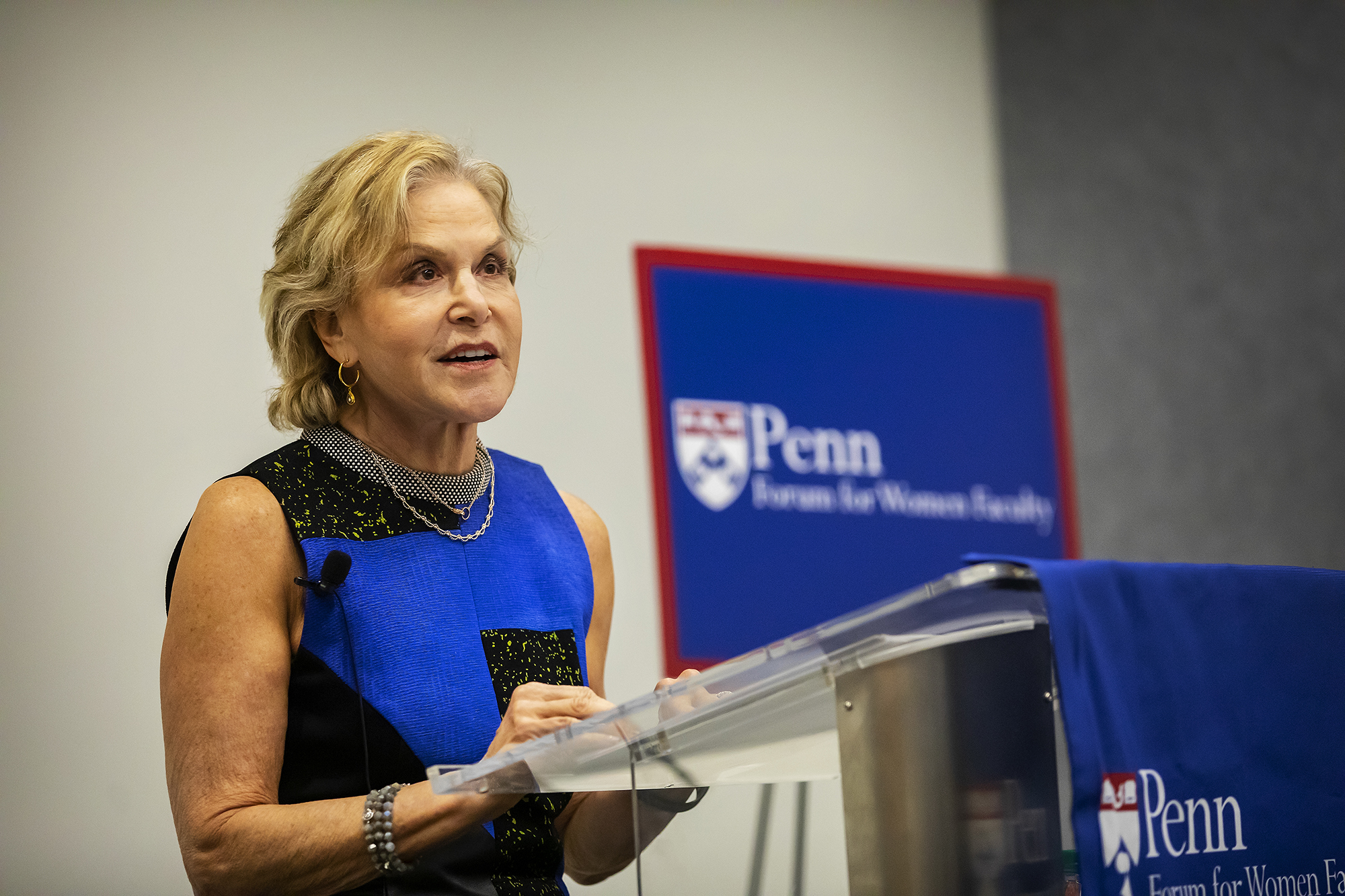

At a packed Penn Dental Cheung Auditorium last Wednesday afternoon, the University welcomed Judith Rodin, Penn’s seventh president and the first woman to be named permanent president of an Ivy League institution, back to campus.

Rodin, who was also the first woman to lead the Rockefeller Foundation, made an appearance to deliver the annual Phoebe S. Leboy Lecture, awarded annually to an outstanding scholar who catalyzes opportunities for women in academia. The lecture was created by the Penn Forum for Women Faculty (PFWF) to recognize Leboy, a professor of biochemistry in the School of Dental Medicine and an advocate for women in science.

“The Penn Forum for Women Faculty is almost 10 years old as an organization, and it’s just been a great honor to bring back Judith Rodin to share her wisdom on leadership and women advancing,” said Marsha Lester, past chair of PFWF and a professor of chemistry in the School of Arts and Sciences. “She’s clearly a phenomenal role model, and we all wish we could follow in her footsteps.

“Phoebe Leboy would be delighted.”

In Rodin’s lecture, which lasted approximately 40 minutes, she discussed her idea of resilience and the five pillars of that concept she’s conceived that every leader—but especially women—can strive toward mastering.

She opened by mulling the curiosity of women leaders being dubbed exceptional at all.

“Throughout my career, I’ve been recognized not just as a leader but as a woman leader. The first woman to permanently lead an Ivy League institution, the first female president of Rockefeller, and to be honest, it makes me just a little crazy,” Rodin said. “At best, I think the distinction is unnecessary, and at worst, the implication is that when it comes to leadership, being a woman may somehow be a liability. Perhaps the reason women leaders are still considered exceptional is that so many women have been actively discouraged from cultivating the qualities needed for leadership.”

Making her case, she cited computer programming as one example of an area where women initially thrived, cracking codes during World War II and developing the famous ENIAC computer at Penn. But, she said, recalling data referenced in a New York Times Magazine report from February, women were sidelined as the decades went on and the image of a computer nerd became largely white and male. That’s partly because, she said, leadership qualities like confidence and decisiveness are punished among women but rewarded among men, hindering their ability to take on leadership roles.

But the stunning result of that history, she argued, has been that women have become more resilient, often naturally boasting some of the leadership characteristics she advocates for.

Rodin interpreted resilience as containing five qualities: diversity, awareness, self-regulation, integration, and adaptability.

Diversity, she said, is the recognition that innovation comes from collaboration and that diverse teams generate better results—and, to boot, she noted that women in leadership roles include and promote other women.

Self-awareness, she said, is not only the most valuable quality of a leader but the product of strong mentoring; she encouraged more mentoring of young women, but also better mentoring, recognizing the difference between being a role model and a mentor—one who acknowledges failures on the way to success.

Self-regulation is the idea of developing a capacity to “fail safely, not catastrophically,” she said, referencing safeguards she helped put into place following a crisis in the 1990s that threatened the sale of the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

Integration, she explained by referencing the “painstaking campaign of listening and research and analysis” to integrate the West Philadelphia community into the University community and revitalize neighborhoods—and noted that women are often excellent at seeing the world from the outside in, because they’ve had that viewpoint their entire lives.

Adaptability, she said, is learning to accept that an effort isn’t working and having the imagination to move on, as women have for decades—“from daughter to wife, wife to mother, from the front desk to the corner office.” She referenced leadership in New Zealand, under Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, as a shining example of adaptability among women, as the country quickly moved to change its gun laws after a March shooting that killed 50 Muslim worshipers at a mosque.

Her larger point, she concluded in the closing remarks of the lecture, is that women are exceptional leaders not despite the fact that they are women, but because they are women.

“To be a woman is to see yourself, for better or worse, as others see you,” she said. “As women, we have a powerful sense of self-awareness. Let us recognize and teach that to the young women who need mentorship. Let us help them to find ways to make an impact on this world. Because we have as much to learn from them as they do from us. To be a woman is to adapt constantly, sometimes drastically. So, let’s help women and men transform the places where we live and work for the better. Let’s work to build a future where our daughters and sons can share even more equally.

“In that world, being a woman leader would not be exceptional; it would be indispensable.”