Comics are increasingly being used in historical storytelling, from professors assigning historical graphic novels in class to scholars collaborating with artists to produce graphic histories on topics on as diverse as the Atlantic slave trade and the decolonization of Algeria.

A recent virtual panel at Penn’s Middle East Center (MEC) explored why this type of sequential art has gained popularity in historical storytelling about the Middle East and Africa and how the art form can transform the way people think about history.

Moderated by Paraska Tolan-Szkilnik, a MEC postdoctoral fellow who earned a Ph.D. in history at Penn in 2020, the discussion featured Trevor Getz , a professor of history at San Francisco State University whose work revolves around gender and slavery in West Africa; Maryanne Rhett, associate professor of Middle Eastern and world history at Monmouth University, whose work relates to modern Middle Eastern and Islamic history at the intersections of popular culture, nationalism, and world history; and Nick Sousanis, associate professor of humanities and liberal studies at San Francisco State, who is a scholar, art critic, and cartoonist, a co-founder of TheDetroiter.com, and the first person at Columbia University to write a dissertation entirely in a comic book format.

Tolan-Szkilnik is herself in the midst of creating a graphic history of two French women and lovers who traveled to Mauritania in the 1930s.

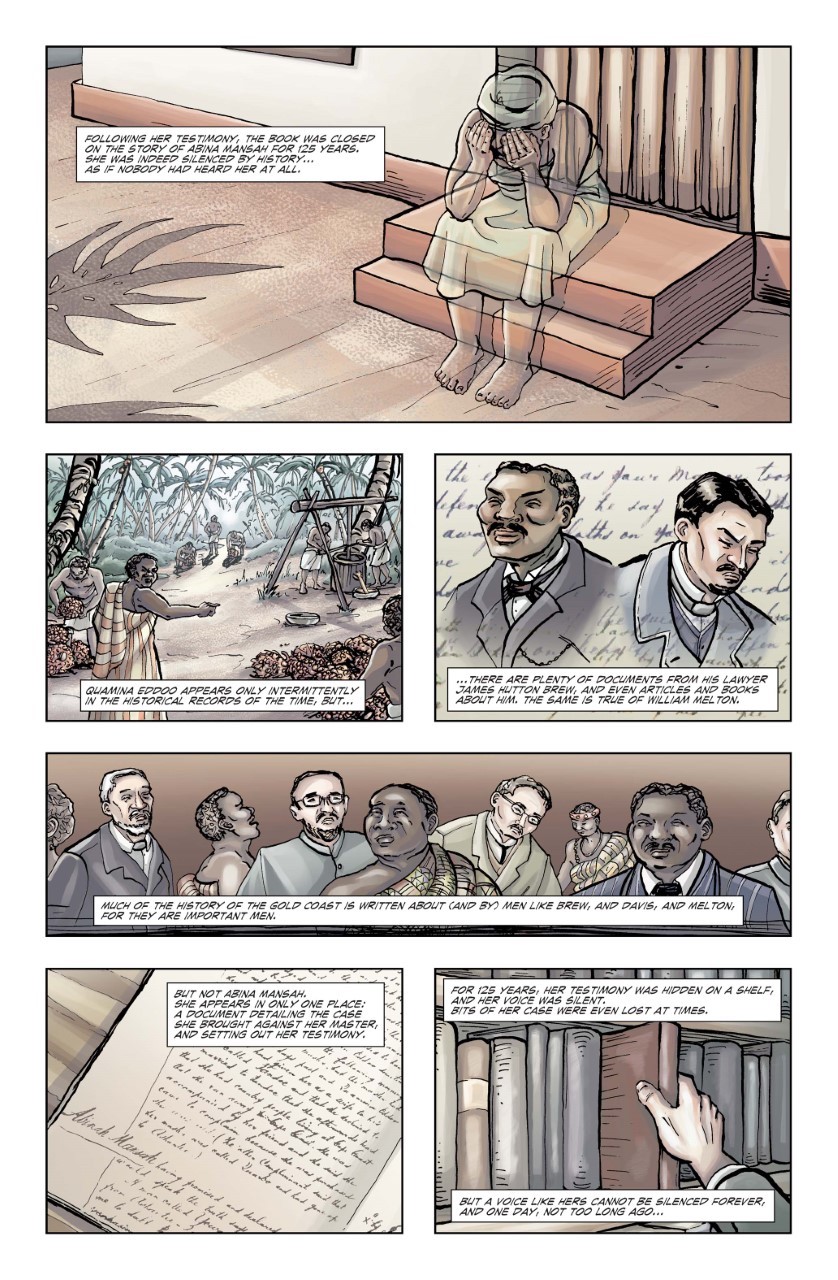

Getz described his work on his 2011 graphic history book, “Abina and the Important Men,” a collaboration with artist Liz Clarke based on an 1876 court transcript of a West African woman who was wrongfully enslaved and took her case to court.

As he was sitting in the National Archives in Ghana almost a quarter of a century ago, he found one source “that really was this moment as a historian that we look to have”: a young woman in a court case prosecuting a man for illegally enslaving her in 1876.

“What stood out for me and what made it immediately relevant, even though I didn't know what to do with it for 10 or 12 years, was the fact that this young woman frequently said things like, ‘I had no will of my own, and I could not look after my body and my health and I knew I was a slave,’” he said.

It’s very rare in the historical record with colonial sources written by colonial men to find and hear somebody like Abina, a young, enslaved, illiterate woman who didn’t speak the language of the courtroom, he said. What started out as a social history dissertation he was writing in which Abina’s case was one of two footnotes, the young woman’s story soon took on a life of its own, he said.

“I finally came to make an argument that I thought I could hear what Abina was saying, and I wanted to share that with people and, frankly, text failed to do that. And thus I turned to comics,” he said. “I wanted to be able to visualize the emotional, the liminal, the corporeal issues that Abina was raising.”

Rhett presented a piece of a chapter she’s currently working on for a book looking at feminism in Marvel comics, a piece on Ms. Marvel, in particular the latest iteration of Kamala Khan, 16-year-old Muslim Pakistani-American from Jersey City, New Jersey.

While the idea of feminism doesn’t have a long history in comics, and the idea of Islamic feminism even less so, the Ms. Marvel series offers a chance to study a Muslim superhero, Rhett said.

She pointed out the hijab as a powerful symbol of self-identity tied up in women’s rights, equality, and patriarchy.

“As with any superhero, the question of the alter ego concealment is a significant one,” she said of the few Islamic superheroines. “The question is intrinsically tied to their marked and unmarked identities as Muslim. Islamic superheroes often utilize conservative Islamic dress as part of their superhero costume, and in this way the hijab, the abaya, the burqa all become tools of concealment identity, at the same time identifying these characters as Islamic.”

She pointed to Faiza Hussain from “Captain Britain,” Dust from the new “X-Men,” the main character from the ongoing web comic “Qahera,” and the “Burqa Avenger.”

She quoted Deena Mohamed, the Egyptian illustrator behind “Qahera” on the reasons behind her work.

“She said, ‘An evening of reading the most awful, misogynistic articles and dumb Islamic websites led me to this. I’ve always kind of wanted to do a webcomic starring a badass Muslim superhero who defends women against the kind of stupid idiocy that we have to put up with every day, whilst shutting up all the white feminists who tried to co-opt the struggle,’ the quote read.”

Although this dichotomy between a Western idea of feminism and non-Western ideals of feminism is nothing new, Mohamed “very succinctly gets at the frustrations many feminists around the world feel at the co-option of the feminist effort by upper class and often white feminists, negating the voices of the vast majority of women around the world,” Rhett said.

Not only can comics and graphic novels be useful for understanding the Middle East and North Africa, but they can help readers gain a “deeper richer understanding of the variation of feminism across the world,” she said.

Sousanis talked about his process and approach to making comics, the interplay between images and text, and the way he pushes past the avatar explaining everything, past illustration and into the use of visual and verbal metaphor.

“Maybe comics allows us some possibilities that we haven’t seen; it allows us to ask questions in ways that we couldn’t without it,” he said.

He likes to think that comics are poetry plus graphic design, as did the Canadian cartoonist Seth.

“That notion of it really allows people to come into making comics whether they have any drawing experience or not,” he said.

Not all of his students can draw, but lettering itself is an art form, and everyone can do it, he said.

“I had a student do a final project, and she was not confident drawing, but she did this thing about being in an abusive relationship in a 10-page, pictureless comic, and it just stopped our class cold.”

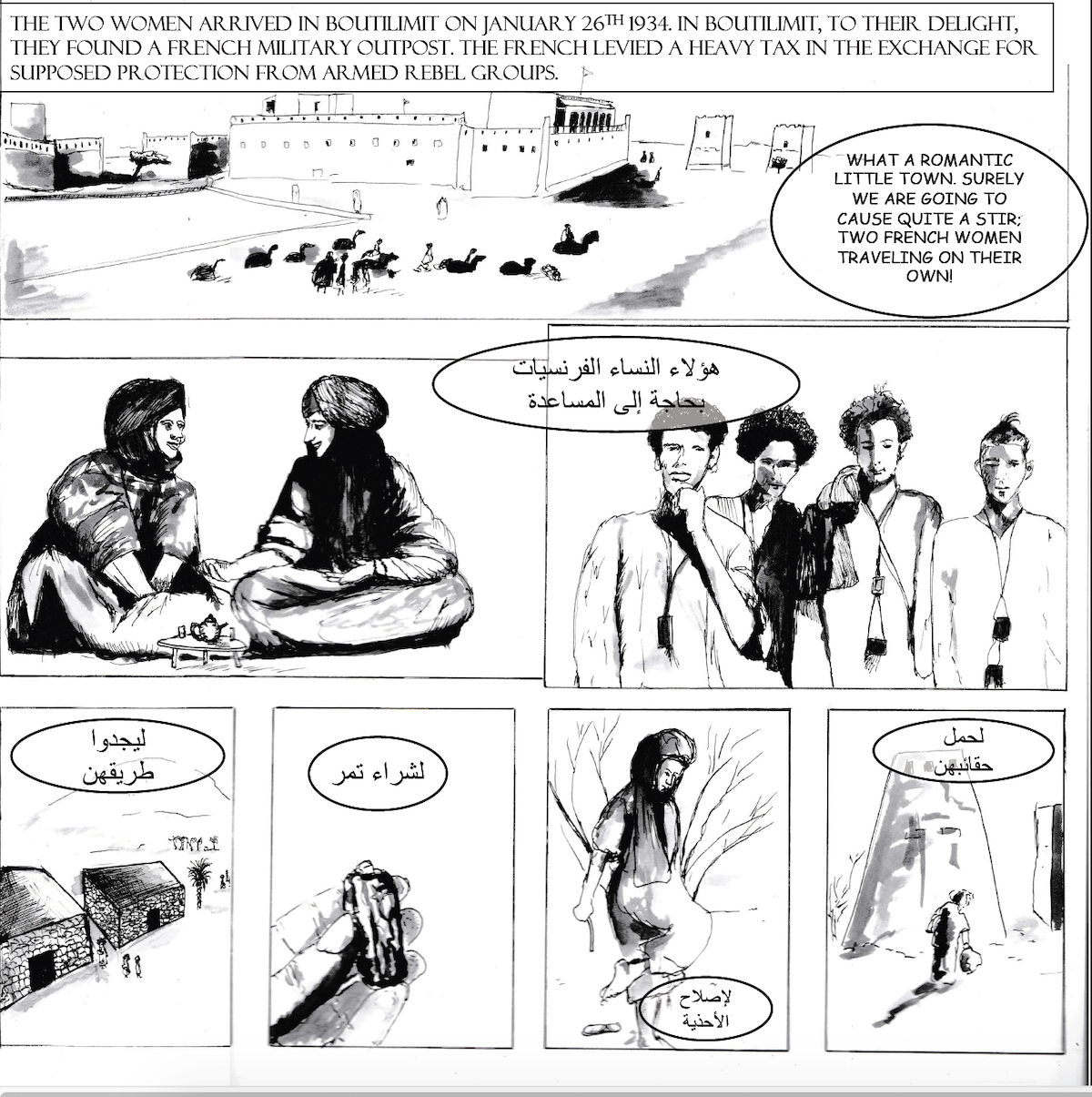

Tolan-Szkilnik is at the beginning of her comic about Odette du Puigaudeau and Marion Senones and their travels in Mauritania in the 1930s.

The two women grew up in Brittany in the west of France, met in Paris, fell in love, and traveled to Mauritania in 1933 for a yearlong trip.

They met locals. They gathered artifacts which they sent back to museums in France and even had a cheetah they brought back to live with them on their boat on the Seine, and actually even took it to the movies with them in Paris, she said.

They figure very little in the scholarship on French exploration of the Sahara, though it’s not for lack of archival sources because they wrote extensively about their discoveries. That can likely be attributed to sexism, she said.

“With this project, I hope to contribute to the literature on gender and colonialism,” she said, and she is using a journal one of the women kept during the time, as well as pictures and drawings they both produced during their stay.

One of the struggles she’s had with the project is how to give humanity to the people that Odette and Marion encountered on their trip from these primary sources. Unlike other explorers in Sahara, they never made an effort to learn Arabic or Fulani or Wolof or any of the languages that people that they encountered throughout their trip. They remained very much colonizers with a mindset of superiority, just like their male counterparts, she said.

“So, in order to give the reader both a sense of the disorientation that these women must have felt but also to give the men and women that these two explorers met an intellectual life, a personal life, I’m hoping to write the book in a multilingual forum,” she said.

During a Q&A session with the virtual audience, the panel was asked how researchers and artists might work together and alongside communities and manage the different needs, goals, and expectations of storytelling that arise, particularly when writing about a race or ethnicity not your own.

Getz said he initially got the process backward in that he had a vision of what he wanted and then connected with an artist. The right way is to work with the artist from the start to best use the medium to convey the idea.

The best example of this, he said, is an almost unknown graphic novel published by the Library Company of Philadelphia called “Ghost River,” about the massacre of the Conestoga in Pennsylvania in the 18th century. It's part of their "Redrawing History" project.

The researcher who instigated it found Native American artists to work closely with the community to draw up the story, and at the end of the comic there are emails and various communications which reveal the process behind creating the work.

“With any work you’re doing where you have a different power dynamic with the community who are the subject of your studies, try to be very reflexive and reveal everything,” he said.