Less than 25 miles south of the Rwandan capital of Kigali sits a red brick Catholic church. From afar it looks peaceful, much like other churches, but, up close, bullet holes and shrapnel marks become visible. Inside, wooden pews hold small mountains of soiled clothing.

The church marks the center of the Nyamata Memorial, one of eight in Rwanda preserved to remember 800,000 people who died in a mass genocide there 25 years ago. April 7 began the country’s annual 100 days of mourning, called Kwibuka. Penn historic preservation professor Randall Mason, who attended the ceremony for the first time this year, has been working with the country’s government since 2016 to protect and conserve such monuments.

“That so many people were killed in such a short time is kind of unimaginable,” says Mason, an associate professor at the Stuart Weitzman School of Design. “But it becomes more imaginable—and even more heartbreaking—when you’re in the country and you see these memorials. They consist of the actual sites where mass murders happened. They were often schools and churches where people thought they would be safe.”

The story of the 1994 genocide actually begins much earlier and requires some understanding of two socioeconomic classes in Rwanda: The Hutus, who were traditionally the laborers and planters, and the Tutsis, traditionally the herdsmen. From the 1920s and ’30s through the 1950s, the colonizing Belgians supported the Tutsis as the ruling class. But in 1959, the Hutus ousted the Tutsi ruler, and the Belgians switched their support, beginning a period of internal violence and exile for the Tutsis.

“Small genocidal incidents started in 1959 and happened through the 1960s,” Mason explains. “There was quite a long lead up to 1994. There is sometimes this misimpression that the genocide happened all at once, that it came out of nowhere, even that it’s a simple story. It’s actually really complex.”

An April 1994 plane crash that killed the Rwandan and Burundian presidents triggered the start of the worst of the mass killings of Tutsis, according to Mason. Before the bloodshed ceased, hardline Hutus would end up taking the lives of hundreds of thousands of their countrymen and driving many more into hiding. By some accounts, nearly three-quarters of the Tutsi population was wiped out. Later that year, the Rwandan Patriotic Front, a Tutsi force based in Uganda and led by Paul Kagame, Rwanda’s current president, defeated the Hutus and stopped the fighting.

Memorials went up almost immediately. “In the aftermath, hasty mass graves were excavated, and human remains and textiles were separated,” Mason says. People started bringing the material remains to central locations, like the church in Nyamata. “The locals had the wherewithal to get officials to deconsecrate Nyamata from being an official church,” he adds. “We don’t know the exact story; people just started piling clothes of the victims on the pews as their simple, straightforward memorial. We’re helping them conserve that.”

Mason and a team arrived in Rwanda three years ago, backed by financial support from the U.S. State Department. The idea was to train government personnel and use Nyamata as a test case to work out how to assess damage and repair these memorials, prioritize projects, and materially treat the buildings and collections themselves. The textiles at Nyamata present an exceptional challenge.

“If you left a pile of clothes out for 25 years in a passively ventilated building, what condition do you think they’d be in?” Mason notes. “They’ve been occasionally cleaned, but when they were originally brought in they were piled on the benches and the floor, piled higher in some places than others. If they’re on the floor, they deteriorate faster because there’s more humidity and easier access for bugs.”

A museum’s typical plan for such materials would prescribe cleaning the clothes and storing them in a controlled environment. But the clothes’ deteriorated condition is part of what makes them meaningful, and Rwandan policy dictates that the collection cannot leave the site. Within Nyamata’s memorial there’s no place to create a controlled environment without changing the very essence of the church itself.

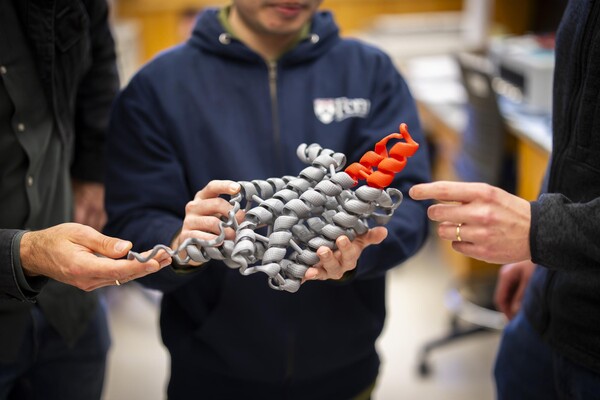

Mason’s team, which includes textile conservator Julia Brennan and Weitzman School adjunct professor Michael Henry, came up with a temporary solution, one that will maintain the clothes for the next decade or two by partially cleaning them. The equipment and materials are all portable, too, the idea being that they can move easily to other memorial sites with textiles. That being said, Mason explains, “if these items are going to exist for future generations, some are eventually going to have to be archived.”

It’s clear that two and a half decades after the genocide, there’s plenty of work still to do. The current Rwandan administration is educating a new generation, many of whom weren’t born in 1994, about its history. And just three weeks ago, a mass grave containing more than 100 bodies from the genocide was discovered near Nyamata.

The fact that the work can make a true difference to Rwandans makes it all the more important to Mason. “There’s a long game here, to be sure,” he says, “but if there’s a way to contribute to protecting these memorials in the short term, that’s an incredible opportunity and honor for us.”

Randall Mason is an associate professor in the Graduate Program at the Stuart Weitzman School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania.