- Who

Jo Tiongson-Perez, chief marketing and communications officer at the Penn Museum, knew plenty of Greek myths and Hans Christian Andersen fairytales—the kinds she would recall to her daughter at bedtime. But why, she eventually mused with college friend Denise Orosa, didn’t she know any Indigenous Filipino stories?

Tiongson-Perez, who grew up in Manila, now engages daily with themes of cultural heritage preservation and storytelling at the Penn Museum. So, after seeing a call for applications in 2020 from The Sachs Program for Arts Innovation, which issued a slew of responsive grants in support of Asian, Asian-American and Pacific Islander Artists at Penn, she decided she could leverage this background to make a difference.

- What

Together with Orosa, a K-12 educator, Tiongson-Perez curated and helped to adapt or translate 11 stories from Tagalog for “Once Upon the Sun and Sea,” featuring illustrations from Filipina artist Tin Javier. The book brings together eight Indigenous stories and added three non-Indigenous folktales that Filipino families might already recognize. The ambition, Tiongson-Perez says, was to “widen the storytelling space to include these types of stories.”

For stories that may not have been written down, she worked with the Byanyas Foundation in Palawan, Philippines, to locate elders from the Tagbanua, one of the oldest Indigenous tribes in the country who were able to orally recreate the stories for later translation. To distinguish which stories were already popular and which were more Indigenous, she consulted with anthropologists. In the process, Tiongson-Perez discovered that many of the Indigenous stories were housed and preserved in the Philippine highlands, which were less likely to be colonized during the Spanish colonial period. These stories also, she explains, tend to have less Western influence, including fewer Christian morals and “neat arcs”—which became a consideration when tackling translation efforts.

“[The stories] are less about the ‘They lived happily ever after’ and more about being and becoming, being OK with this moment in time and this continuum of existence,” says Tiongson-Perez. “I wasn’t used to that, so we did our best to honor the original intent of the stories as opposed to wondering, ‘Where is the resolution?’”

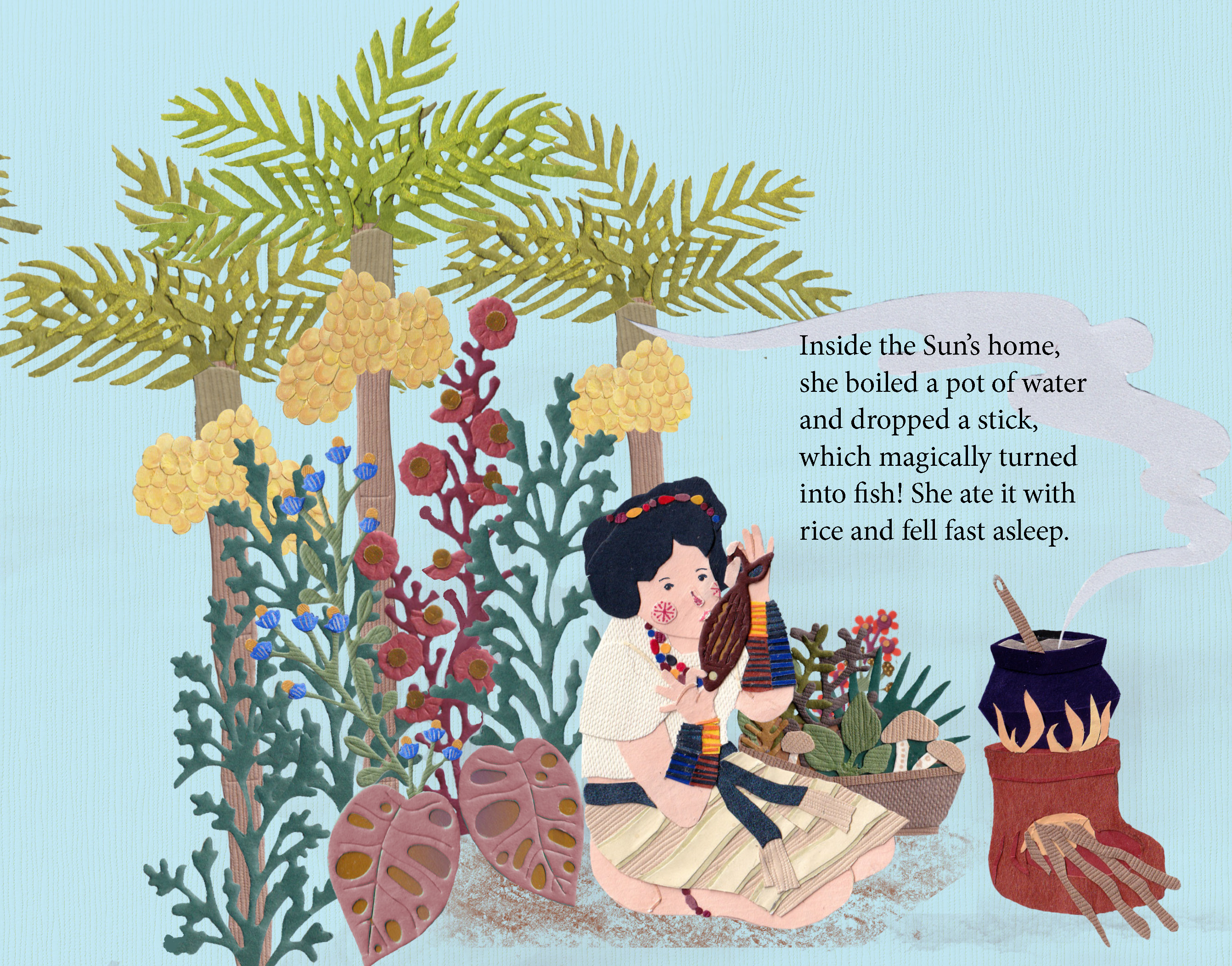

The illustrations, meanwhile, apply the mixed-media methods of Javier, who used a punched paper and collage method and rigorous research methods to incorporate patterns, colors, and elements of nature that honored both the Filipino storytelling tradition, flora, and fauna, including textiles.

- Why

While researching what Indigenous stories had already been identified and which to include in their book, Tiongson-Perez says she and Orosa were surprised by some of the historical characterizations they read.

“We encountered a lot of characterizations of the stories and culture as primitive, or savage, or even ‘weird,’” she says, recalling anthropological introductions she found from the early 1900s. “Their introductions were framing it as a big ‘othering,’ and it made us think then that this could be a way to challenge those historical characterizations.”

The book, she says, presents an opportunity to celebrate these stories as much as the Western counterparts she grew up with.

One story included, “Aponibolinayen and the Sun,” is an excerpt of an Itneg story about a female character who enters “Init-init,” or the realm of the sun. It begins a bit like “Jack and the Beanstalk,” Tiongson-Perez says, except there is no tidy ending and the trajectory of the character vastly differs.

“She enters this realm, and the sun is fascinated with her, and she’s all about negotiating her space—her right to coexist in that space as she’s also exploring, and it’s so very different from the fairytales I grew up with where female characters are always waiting for something to happen to them and their life doesn’t happen until then,” she says.

Instead, the character is “asserting her own being.”

“I wonder how I would have thought about things if I’d heard that earlier in my life,” Tiongson-Perez adds.

She and Orosa will read from the book and do a signing at the March 9 edition of the Museum’s CultureFest! series. “Once Upon the Sun and Sea” is available to buy through various online retailers and Harriett’s Bookshop in Fishtown.

Upon finishing the book, Tiongson-Perez says, she was finally able to read out loud one of the Indigenous Filipino stories to her daughter—even if she is 15.

“It was fun to do that!” she says.