Around the nation in the summer of 1970, state legislatures made up of mostly white men were debating whether to legalize abortion at the state level.

“There were no women’s voices or women’s stories; we were just not in those debates,” says Mary Summers, senior fellow at the Fox Leadership Program and a political science lecturer. “It was pretty much all men, and they were voting against women having access to abortion.”

Having just graduated from Radcliffe College, where she participated in the anti-war student movement, Summers was increasingly interested in the women’s movement. She connected with a group of women in Boston who were developing one of the first documentary films from the perspective of women about the right to safe and legal abortion.

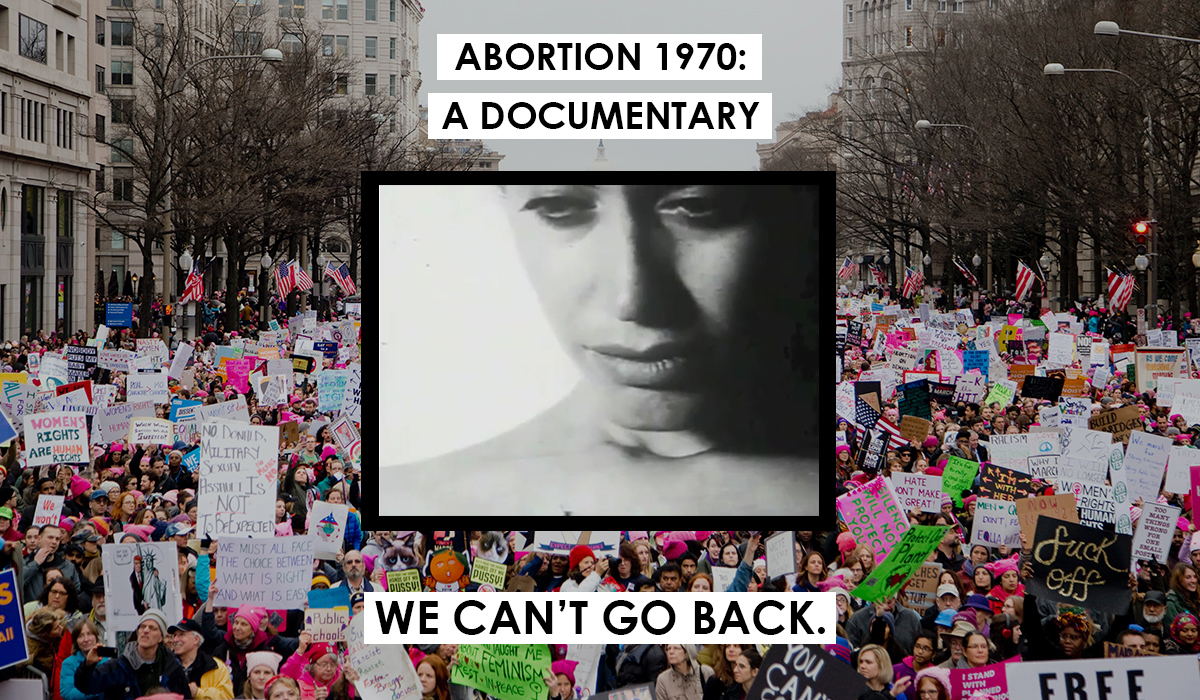

During the course of a year, Summers; Jane Pincus, who went on to co-author the seminal book on women’s health, “Our Bodies, Ourselves,”; Catha Maslow; and Karen Weinstein created a film that, Summers says, aimed to amplify women’s voices, convey women’s experiences, and show that access to abortion was crucial to women’s lives and rights.

The film tells the illegal-abortion stories of two women—one working class, one middle class—and highlights their fears, financial strains, and health worries. It also, Summers says, tackles the fact that the vast majority of women dying from illegal abortions were poor women of color. The film’s conclusion speaks to the broader issues of what women need in order to live healthy lives, including decent jobs, health care, child care, and an end to poverty and racial discrimination.

The group wrapped up the film in 1971, with the idea it could be used by various groups for state-by-state organizing efforts, Summers says, and it was shown on a few college campuses. By the end of that year, the four women had gone their separate ways, each taking their next steps in their future careers. Then in 1973, the United States Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision legalized abortion throughout the nation, and the sense of urgency to distribute the film waned.

About three years ago Weinstein reconnected with the original group except for Maslow, who died in 2015. Weinstein urged them to make one more push to get the film out in the world and to add their names as filmmakers for the first time.

“The credits of the original film just said ‘made by a collective of women’ because we were dashing to get it done,” says Summers, “and we couldn’t resolve disagreements about putting our names on it.”

Working for the next several years with help from a research assistant, editors, and old friends, they created a website where the updated film, together with ways to get involved in today’s fight for abortion rights, are available free. The site went live at the beginning of April, just a month before a leaked draft opinion showed the Supreme Court was poised to overturn Roe.

“Our initial hope was that we could reach out to all these amazing organizations that are working for abortion rights and offer the film to them as a resource, whether they want to put the link on their website or in a newsletter or have a fundraising event,” Summers says. Now, the film not only shows viewers what an America without safe and legal abortions looked like but functions as a reminder of what could be in store should Roe be overturned.

It’s been 50 years since Summers’ main focus was legalizing abortion. After making the film got her involved in thinking about health care, she became a physician assistant. Her interest in politics resulted in her also becoming a speechwriter for politicians including Jesse Jackson during his 1984 presidential run, before earning a master’s degree in political science at Yale.

Her experience with political campaigns in the 1980s got her interested in the way that the family farm movement brought farmers, environmentalists, and anti-hunger advocates together to challenge U.S. agriculture policies. The history of agricultural and anti-hunger policy and politics became an ongoing focus of her academic research.

Summers says she came to Penn because she was impressed by the University’s support for academically based service learning. Here, her popular Politics of Food and Healthy Schools courses have involved students in working with SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) enrollment campaigns and school meals, recess, cooking, and gardening programs in the Philadelphia schools.

Looking at the abortion issue now, Summers says she’s very concerned.

“I have to say my feeling when I saw the draft ruling was just incredible sadness,” she says. “Thinking of all these women in all these states, where abortion clinics are closing down. People’s lives are so hard right now, and this just makes them so much harder.”

She notes that the biggest positive difference from the pre-Roe world is that medical abortions are now widely available. “Getting pills to people is easier and less dangerous than a surgical procedure,” she says.

Reflecting on the 1970s, she says she is struck by the many people willing to challenge the law at the time, including women in the Jane Collective in Chicago who performed thousands of safe but illegal abortions, risking going to jail.

Of this moment Summers says, “When you think of how much abortion has been criminalized and medical professionals have been restricted in many states from even speaking to their patients about abortion, why is there not more of a huge uproar? In the 1970s people were willing to go to jail in order to help women access support, and we’re not seeing that anymore. All you see is ‘donate, donate, donate.’”

She says political debates today are dominated by people tweeting sound bites, rather than organizing to seek common ground in improving people’s lives.

“The movement for abortion rights in the 1970s was part of a bigger movement, says Summers. “We were fighting for women who needed access to safe abortions and for women who felt forced into having an abortion because they couldn’t afford to have a child. But after the success of the neoliberal attacks on government in the 1980s in the name of free markets, we have not seen big organizing efforts for policies that would result in greater justice, equality, and opportunity for everyone. Instead, we have had decades of Democratic politicians who look like they’re trying to cover up what they really think, which is not going to win voters over.”

Summer says she encourages people frustrated and angry about the possible overturning of Roe to get involved, whether it is organizing, lobbying, outreach, or mutual aid.

“If you get involved in trying to change laws and institutions and help people who are being hurt by laws and institutions, you meet other people trying to change the world, and you see the difference you’re making. That’s how I survived all these years. I’m still convinced we can defend abortion rights,” she says. “I would love to see law students, medical students, and nursing students talking about how to challenge these state anti-abortion laws in a big way.”

It’s hard to keep unjust laws on the books if more and more people are breaking them, she says, pointing to segregation as an example. “This country fought a civil war in order to say your opportunities for liberty should not depend on where you live. The right to abortion is critical to liberty for women. This is one of the most intimate and most important decisions of your life. It’s a free speech issue, and it’s a personal liberty issue.”

She says a lot of politicians have used the abortion issue in a cynical way. “There are many other people who are genuinely against abortion, but who might agree with me on many other things. The fact that we’ve lost the ability to work together to promote life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness on what we do agree on is why we’re in the state we’re in now.”

It’s important to keep trying to find common ground, says Summers. “To me, organizing has always been trying to reach out to other people, to see where they agree with you, to figure out how to work together to get somewhere.”

The film can be viewed on the newly launched website, https://www.abortionandwomensrights1970.com/