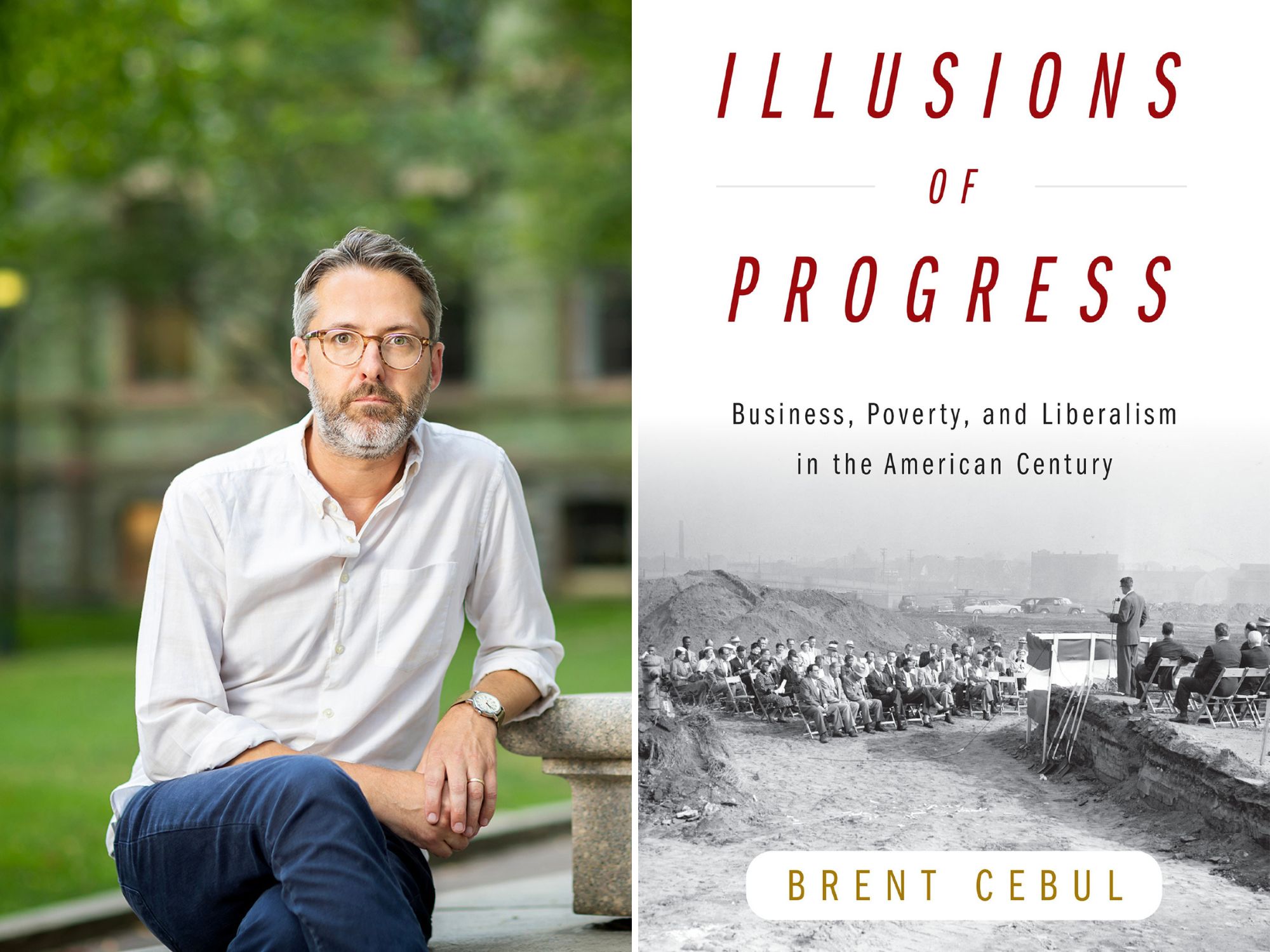

The following is an excerpt from “Illusions of Progress: Business, Poverty, and Liberalism in the American Century,” by Penn history professor Brent Cebul of the School of Arts & Sciences. (©2023 University of Pennsylvania Press)

In the summer of 1976, Sarah Turner brought pieces of her home’s crumbling banister to Washington, D.C. She and 100 others, each carrying fragments of their deteriorating houses, barricaded themselves in the lobby of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). From the pieces of their homes, they built a shack. A resident of Cleveland, Ohio’s Buckeye neighborhood, Turner was among 2,000 activists who traveled to Washington for a series of demonstrations and public hearings. Turner provided for her eight children with domestic work, and under a recent federal program, she was able to purchase her own house. But HUD and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) failed to ensure the properties were adequately inspected—many were literally falling apart. Faced with overwhelming costs to make them livable, poor and working-class Americans, disproportionately of color, were locked into utterly untenable mortgages. Though HUD set aside funds to support essential home improvements, Turner and her allies called attention to the many ways “community development” subsidies were instead underwriting elite, business-led, higher-end commercial and residential developments. In their testimony before Congress and as their makeshift shack in HUD’s lobby testified, these citizens pressed the federal government to support affordable, safe housing and redevelopment of poor neighborhoods as much as it did high-end commercial and residential developments.

Battles like these, waged over the distribution and administration of public resources, flared across the 1970s, a decade of seismic fracturing and reformation of American politics and economics. This was a time in which resurgent conservatives, corporate titans, and pro-market intellectuals championed market-oriented policies and called for hollowing out and eliminating liberal programs intended to insulate citizens from the market’s vagaries and depredations. Indeed, at the very moment protesters barricaded themselves in HUD’s lobby, President Gerald Ford’s administration was inviting local chambers of commerce—the same business elites whose command of antipoverty and development subsidies activists protested—to carry out commercial versions of “community development.” Several weeks after Sarah Turner traveled to Washington, Ford’s HUD secretary traveled to Cleveland, where she underscored for business leaders the kinds of partnerships they sought: “this nation’s private sector and this nation’s government constitute an insoluble partnership—and verifies the proposition…that the Federal government, working through the private sector, can have a vital role in both housing and the economy.” In emphasizing the administrative authority of elite-led public-private partnerships, community development and antipoverty programs became an early battleground in conservative efforts, as Ford administration officials put it, to roll back the “ponderous federal red tape, bureaucracy, and lack of flexibility” built up over four decades of liberal governance.

The New Deal “order,” as scholars have described the configuration of governance and rights that liberals began constructing in the 1930s, developed unprecedentedly vigorous federal protections for individuals and families—guaranteeing labor’s right to organize, delivering generous subsidies for housing, higher education, and secure retirements. The new age, then, would be one of public-private partnerships, privatization, deregulation, and devolution. For many scholars and journalists, these emergent practices signified an epochal breakpoint—the transition to a neoliberal age.

To assert such a sharp break between seemingly distinct “orders” of governance, however, would be to miss the ways in which the assumptions, policy tools, and practices of the new era depended upon, reformulated, and evolved from the old. As this book argues, market-oriented approaches to social problems, public-private partnerships, financialized and fiscally frugal governance, all often held up as symbols of neoliberalism, were deeply embedded in New Deal and midcentury practices of governance. By 1976, local clashes over the private sector’s role in administering liberal initiatives had been decades in the making. By then, those public-private, federal-local practices were being reframed and redeployed as checks not only on multiracial insurgents such as Sarah Turner but on the liberal state more broadly—and not only by conservatives but also by a rising generation of liberals. Less a sharp historical breakpoint, then, what community activists confronted in Washington, D.C., in 1976 was rather an historical hinge. Battles with the Ford administration certainly augured a more austere social contract in the making. But, as this book argues, many of that social contract’s terms were first articulated in liberalism’s public-private approaches to urban, economic, fiscal, and racial governance.

By tracing the emergence and proliferation of local-national, public-private governance back to the New Deal, Illusions of Progress recovers a history of domestic market development initiatives in which seemingly oppositional forces—the interests of liberals and business, the public and private sectors, and the local and national—proved, in practice, to be highly complementary. Beginning in the 1930s with New Deal works programs, liberals regularly empowered local political and business elites to administer an evolving array of federal initiatives. For liberals, localism, market creation, public-private partnerships, and publicly secured financing routed through federalism, chambers of commerce, real estate interests, bankers, developers, and bond markets, all of which were hallmarks of the New Deal’s public works and housing agendas, promised to meet the crisis of the Great Depression and deliver an expanding range of economic and social goods. And they promised to do so without creating overly centralized state authority or durable direct expenditures.

This worldview, which this book calls “supply-side liberalism,” was born in the late New Deal, when liberals situated targeted public investments in and insurance for commercial, industrial, and residential development as wellsprings of virtuous cycles of economic growth and expanding tax revenues that might also underwrite a broader progressive social agenda. These commitments characterized not only the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the economic planning proposals of the National Resources Planning Board (NRPB) but, following World War II, the expansive economic and social visions of the Federal Housing Administration and urban renewal. By the late 1950s, in the wake of the McCarthyite assault on the left and as Cold War anticommunism crescendoed, many supply-side liberals had even come to believe that publicly structured, business-administered developmental partnerships, credit and security instruments, and debt markets might, in John F. Kennedy’s famous phrase, create “a rising tide [that] lifts all the boats.” Kennedy, in fact, borrowed his phrase from a New England business and civic association. Far from simply the product of macroeconomic, Keynesian fiscal policy, frequently dubbed “growth liberalism,” liberals’ rising tide rested upon a vast but often submerged flow of targeted, localized, and structural interventions in markets. Yet, by binding national visions of social progress to the local interests of capital—that is, by endowing white business elites and fiscally precarious subnational governments with broad discretion over the shape and uses of significant federal resources— supply-side liberals very often entrenched racial inequalities of democratic power and economic opportunity they imagined their policies solving.

By the mid-1960s, the illusory nature of these solutions for poverty and racial or social inequalities was increasingly clear. For a moment, progressive policy activists within Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty sought to empower impoverished and racially marginalized citizens to administer their own federal community development and antipoverty programs. They would not simply make poverty survivable, as much of liberal antipoverty initiatives had previously intended; they would transcend it through an ethic of “self-help.” A vast ecosystem of civic associations surged forth—churches, civil rights organizations, welfare rights groups, housing advocates, and community activists—undertaking economic development plans, staffing new social service and youth centers, pursuing home improvement initiatives, and starting jobs training programs. The War on Poverty’s famous mandate to ensure the “maximum feasible participation” of poor people ratified decades of African American grassroots organizing that sought not simply electoral enfranchisement or racial desegregation but, as this book terms it, administrative enfranchisement within the many federal-local programs and public-private partnerships whose white, elite leadership so often exacerbated inequalities in marginalized communities.

For those local elites, meanwhile, the prospect of poor and minority citizens administering their own programs—that is, exercising state power—was too much to bear. Faced with blowback from key constituencies including mayors, businesspeople, and members of Congress, Lyndon Johnson himself moved quickly to claw back maximum feasible participation mandates by bringing local private-sector elites back in, a process completed by the Nixon and Ford administrations’ New Federalism reforms. By 1976, this brief window of opportunity had slammed shut. Federal community development funds were, once again, underwriting local elites’ development agendas to the detriment of poor communities.

The seeming intractability of neoliberal policy tools and political consensus, then, owes much to the institutional arrangements, partnerships, and political-economic and political-cultural logics of liberalism’s supply side, which had positioned local business elites as effective social actors, administrators, and civic leaders since the 1930s. By the tumultuous 1970s, four decades of liberal economic-qua-social governance had taught those businesspeople to frame their civic activities and profit seeking in precisely these terms. During that decade’s economic, political, and fiscal crises, a new generation of Democrats reinvented liberalism’s supply side, but they began applying its methods in new realms. Decentralism, public-private partnerships, and market-oriented solutions became plausible ways to reform contested social programs and entitlements, perhaps even offering means to both reinvent government and muzzle multiracial interest groups pushing for meaningful enfranchisement within the Democratic base and American democracy. That citizens like Sarah Turner were relegated to the margins of both eras, however, does not mean that they were the same. Rather, it was in the real but fleeting possibilities of the 1960s and 1970s, in the transitory chance that the New Deal’s social promise might meaningfully empower impoverished, minority citizens, that new generations of liberals and conservatives repudiated the old order. With many of its tools they began building something new.

The text above is excerpted from “Illusions of Progress: Business, Poverty, and Liberalism in the American Century,” by Penn history professor Brent Cebul, copyright ©2023 University of Pennsylvania Press. Used by arrangement with the publisher.