Born in Johannesburg and raised in Allentown, Pennsylvania, Sara Byala took a course on South African history during her first semester as an undergraduate at Tufts University, and that set the course of her career. Byala went on to earn a Ph.D. at Harvard.

Throughout her life she has travelled to Africa, to visit relatives after her family moved to the United States in the 1970s and for academic research, including her dissertation on 20th century South Africa. She noticed that no matter where she went, even in the most remote corners of the continent, Coca-Cola was there, often ice-cold. The brand, with its iconic red sign, is ubiquitous.

“The more I travelled around the continent, the more I realized Coca-Cola is everywhere in Africa,” says Byala, who has been a senior lecturer in critical writing in the School of Arts & Sciences since 2007.

In 2014 she read about Coca-Cola bottlers creating a rainbow with recycled water over downtown Johannesburg, a nod to the country’s moniker Rainbow Nation, to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the end of apartheid. At that moment she made a decision. “I thought now is the time to write this book. Somebody has to do this,” she says.

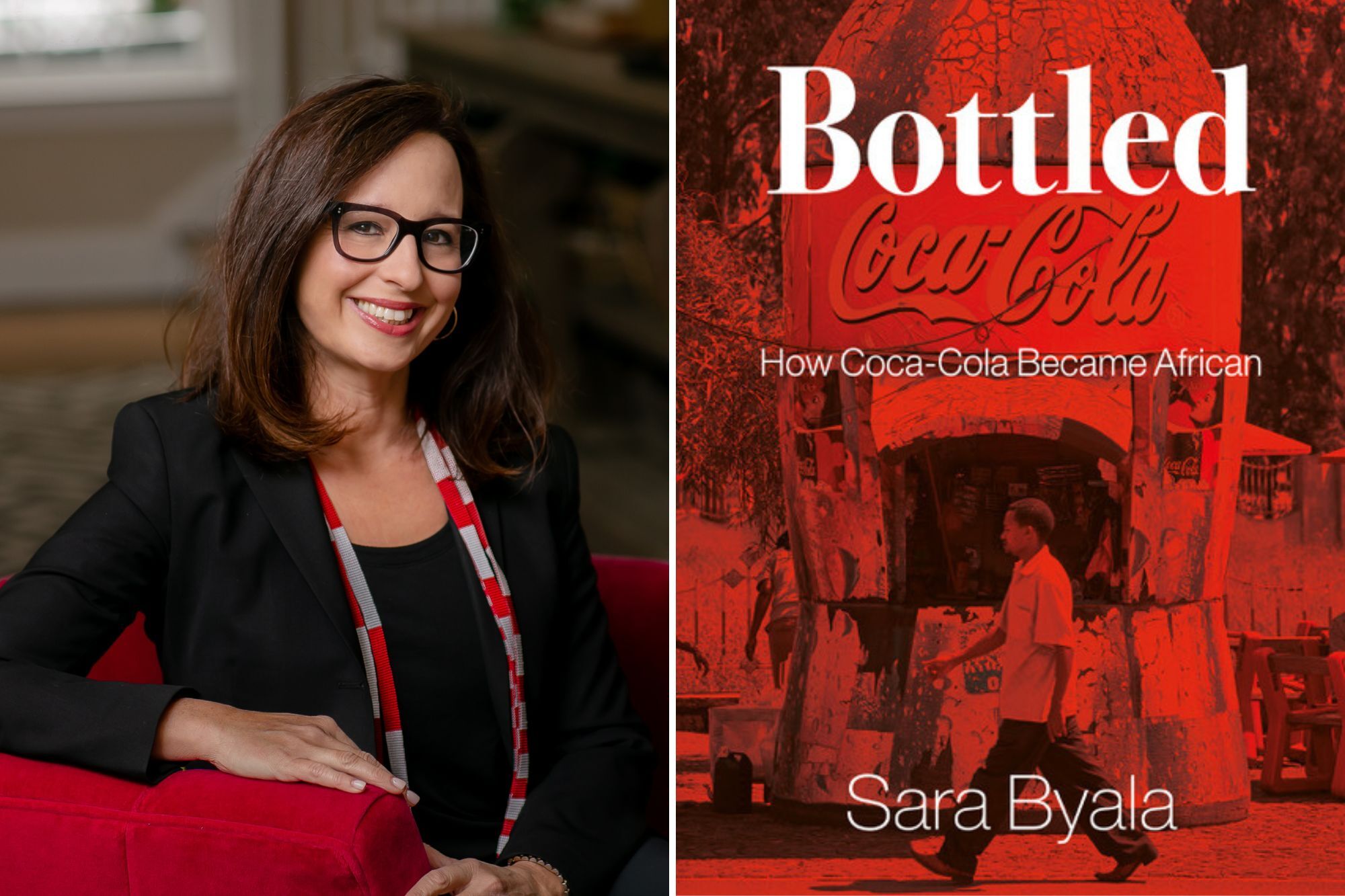

That book, “Bottled: How Coca-Cola Became African,” was released this month in the U.S., after its initial publication in the United Kingdom and Africa.

“Bottled,” Byala says, is the first assessment of the social, commercial, and environmental impact in Africa by one of the world’s biggest brands and largest corporations. Through a combination of archival research and on-the-ground fieldwork, she examines the company’s century-long involvement in myriad aspects of life on the continent. “This is not a story of American capitalism running amok but rather of a company becoming African, bending to consumer power in ways big and small,” she says.

Byala’s ancestors arrived in Africa from Europe and the Middle East. Her mother was born in Zimbabwe, her relatives resettling in Africa from Russia and Eastern Europe. Byala’s father was born in South Africa, his mother having left the Netherlands right before the Holocaust. “They were all part of the Jewish diaspora that sought refuge in Africa,” says Byala, who became a U.S. citizen when she was 18.

At Penn, she teaches a range of writing seminars about Africa, including one on Coca-Cola, and will use her book for the first time in a course next year. Byala is also the associate director of the new Penn Global Documentary Institute, that aims to tell global stories through local collaboration. She has travelled extensively with students in Africa through her research and through Penn Global Seminars.

Penn Today spoke with Byala about her research and writing, her work with students, and her hopes for “Bottled.”