A gene encoding a protein linked to tau production—tripartite motif protein 11 (TRIM11)—is found to suppress deterioration in small animal models of neurodegenerative diseases similar to Alzheimer’s disease (AD), while improving cognitive and motor abilities, according to new research from the Perelman School of Medicine. Additionally, TRIM11 is identified as playing a key role in removing the protein tangles that cause neurodegenerative diseases, like AD. The findings are published in Science.

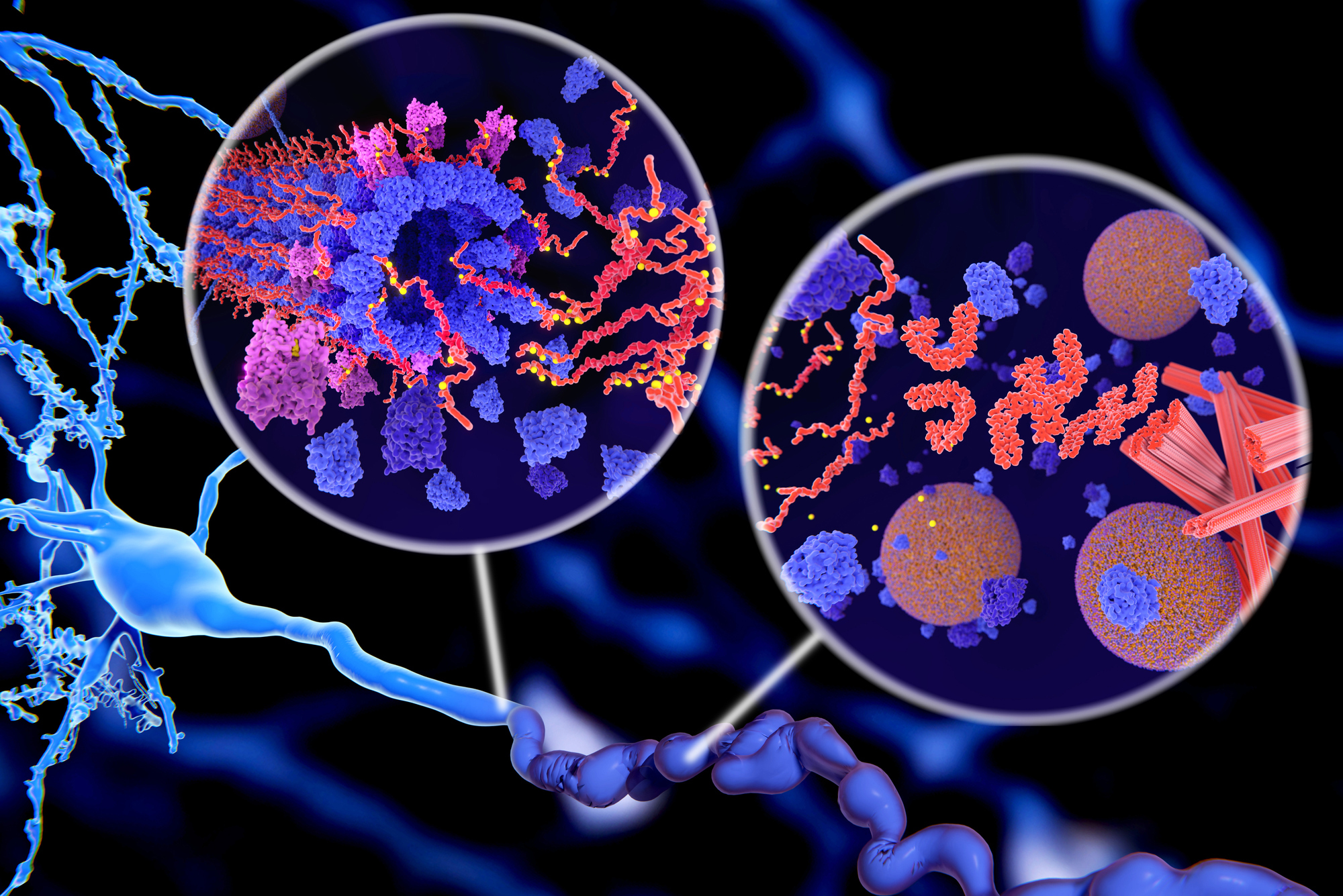

AD is the most common cause of dementia in older adults, with an estimated 6 million Americans currently living with the disease. It is a progressive brain disorder that slowly destroys memory and thinking skills. Foundational research at Penn Medicine led by Virginia M.Y. Lee, the John H. Ware III Professor in Alzheimer’s Research in Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, and the late John Q. Trojanowski, a former professor of geriatric medicine and gerontology in pathology and laboratory medicine, reveals that one of the underlying causes of neurodegenerative diseases is neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) of tau proteins, which cause the death of neurons, leading to the symptoms of AD, like loss of memory.

In addition to AD, aggregation of tau proteins into NFTs is associated with over 20 other dementias and movement disorders including progressive supranuclear palsy, Pick’s disease, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, collectively known as tauopathies. Nevertheless, how and why tau proteins clump together and form the fibrillar aggregates that make up NFTs in patients with these diseases remains unclear. This major gap in knowledge has made the development of effective therapies challenging for researchers.

“Most organisms have protein quality control systems that remove defective proteins, and prevent the mis-folding and accumulation of tangles—like the ones we see with tau proteins in the brain of those with taupathies—but until now we didn’t know how this works in humans, or why it malfunctions in some individuals and not others,” says senior author, Xiaolu Yang, a professor of cancer biology at Penn. “For the first time, we have identified the gene that oversees tau function, and have a promising target for developing treatments to prevent and slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease and other related disorders.”

Read more at Penn Medicine News.