This Nurse Means Business

Starting out as a nurse practitioner -- nope, no one starts out as a nurse practitioner. Everyone starts by being born. Starting out at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania as an infant, and returning to Penn as a post doc, School of Nursing Professor Barbara Medoff-Cooper became a nurse practitioner and a nurse researcher who is part of a business based on her research, is doing reasearch based on her business, and it's all related to babies.

There's more. A baby who Medoff-Cooper cared for in the newborn nursery and in her practice grew to be a nursing student whose work-study job is to help Medoff-Cooper, PhD, CRNP, FAAN, who, by the way, is also the new director of the Nursing School's Center for Nursing Research.

But let's get back to the business -- Bioflow.

Bioflow grew out of Medoff-Cooper's research on the all-important ability of babies to suck. And her research grew out of her experience as a nurse-practitioner: She wanted to know how to identify which babies were at risk.

"We need multiple ways to assess their development," she said. The need is critical in low-birthweight infants, who frequently have a variety of developmental deficits.

One effective way to predict babies' risk is by assessing their brain metabolism.

But the only way to measure that "is by putting an infant in a giant magnet, a spectrometer," says Medoff-Cooper. She was looking for a simpler system. That's when she came upon a study showing that sucking patterns indirectly tell us about babies' brains.

Easier said than done. No system for measuring sucking patterns existed.

"To measure feeding for premature infants, we needed instrumentation," she said.

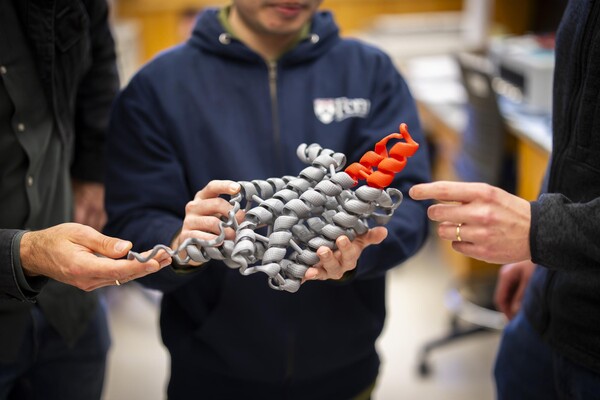

With Professor of Bioengineering Mitchell Litt and Associate Professor of Psychiatry Reuben E. Kron, Medoff-Cooper went to work developing a way to measure a babies sucking patterns. Starting with a Benjamin Franklin Partnership Grant and then a Small Business Initiative Research Grant from the National Institutes of Health, Bioflow has advanced from determining that such a device would work to hiring an executive and designing a prototype. The prototype, called the neonatal nutritive sucking instrument, has what looks like an ordinary baby bottle and nipple. A transducer on the nipple measures the changes of pressure within the nipple created by the baby's sucking and then translates the pressure changes into an electronic signal that is fed into a device that records and prints out the pattern of the sucking. The pattern also appears on a monitor.

In her research, supported by an NIH grant from the Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Medoff-Cooper uses a prototype of the instrument, as do researchers in several hospitals across the country. The prototypes measure more than feeding. They simultaneously measure other key parameters -- like breathing, oxygen saturation and heart rate -- all displayed on a monitor right at the baby's bedside.

The measurements will help Medoff-Cooper and other researchers determine standards for diagnosing the significance of different sucking patterns by developing correlations between sucking behavior and standard measures of growth and development.

The final product, which will be ready in about two years, will measure only the sucking behavior because norms will have been established.

Poor feeding, says Medoff-Cooper, can indicate a number of problems. For one, there's the problem she started with -- brain development.

"A baby has to coordinate breathing and feeding patterns or we worry abut the CNS [central nervous system] integrity," Medoff-Cooper says. A baby who stops breathing while feeding is having trouble. Poor feeding can also show that a baby doesn't feel well or has an infection.

"Feeding patterns are very sensitive," she says. "[The neonatal nutritive sucking instrument] could be used as a standard part of assessing a baby's state. Feeding skills are a criterion of discharging for low-birthweight infants."

Health care professionals need multiple ways to assess the baby's development, not only for low-birthweight infants, but also for full-term infants who may be having problems. A baby who seems otherwise ready to go home from the hospital but is not feeding well may not be ready to go home after all.

The beauty of Bioflow's device is that it's convenient for follow-up assessments several weeks later:

"It's cheap, non-invasive, portable and you get instant feedback," says Medoff-Cooper.

As for the baby who grew up under Medoff-Cooper's care to become a nursing student, she's Chris Kelly, the young woman standing in the photograph on the cover of the Almanac.