What did Spain hope to gain from Magellan’s voyage?

There was strong competition between Spain and Portugal to dominate different parts of the world, and Magellan’s voyage has quite a lot to do with this competition, not so much with scientific or geographic knowledge.

By the Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in 1494, and other pacts, Portugal and Spain agreed on the need to regulate the various spheres of geopolitical influence. Spain got the monopoly of expeditions and control over all territories they encountered going west—towards the land we now know as America. Portugal in turn received a monopoly over trading routes and territories in the south and east. In many ways, both polities decided to divide the entire world into two areas of influence: one controlled by the Portuguese, including Africa and Asia; the other controlled by the Spanish monarchy, encompassing almost the entire American continent, and some areas in the Pacific and Asia.

There were, however, some points of contention among both monarchies. One was Brazil, where Spaniards and Portuguese would disagree for centuries about the extension of their power. More important were the disagreements on the other side of the world, in Asia, the rich land of trading. The disagreements resulted from the inability to clearly delimit the areas of influence assigned by the Treaty of Tordesillas. The Portuguese believed they had a monopoly over trade and settlement in all important trading centers, and the Spaniards believed some of these areas belonged to their king according to the treaty.

It is in this context that Magellan offered a plan that, respecting the agreement, would give Spain the right to trade and settlement in areas that, until that moment, were controlled by the Portuguese. His proposal was simply to cross the Americas and get to Asia through the back door. The Spanish ruler was evidently happy to hear this, because it would allow his subjects, merchants, and sailors to become players in the wealthiest economic center of the world.

What made this three-year journey particularly challenging?

They already knew that there was a continent between Europe and Asia—the New World, or how Spaniards liked to call it, the Indies. But they didn’t know exactly the extension of this continent, in the north or the south, or whether or not there was a clear passage that would allow sailors to cross to the Pacific. In many senses, they had no idea where they were going, the distance between America and Asia, what were the challenges, and the dangers, or how long it would take them. Compared to the Magellan’s voyage, the Portuguese navigation through the south and east passage, was relatively simple. It was dangerous, it took a long time and many lives, but it was relatively known and predictable.

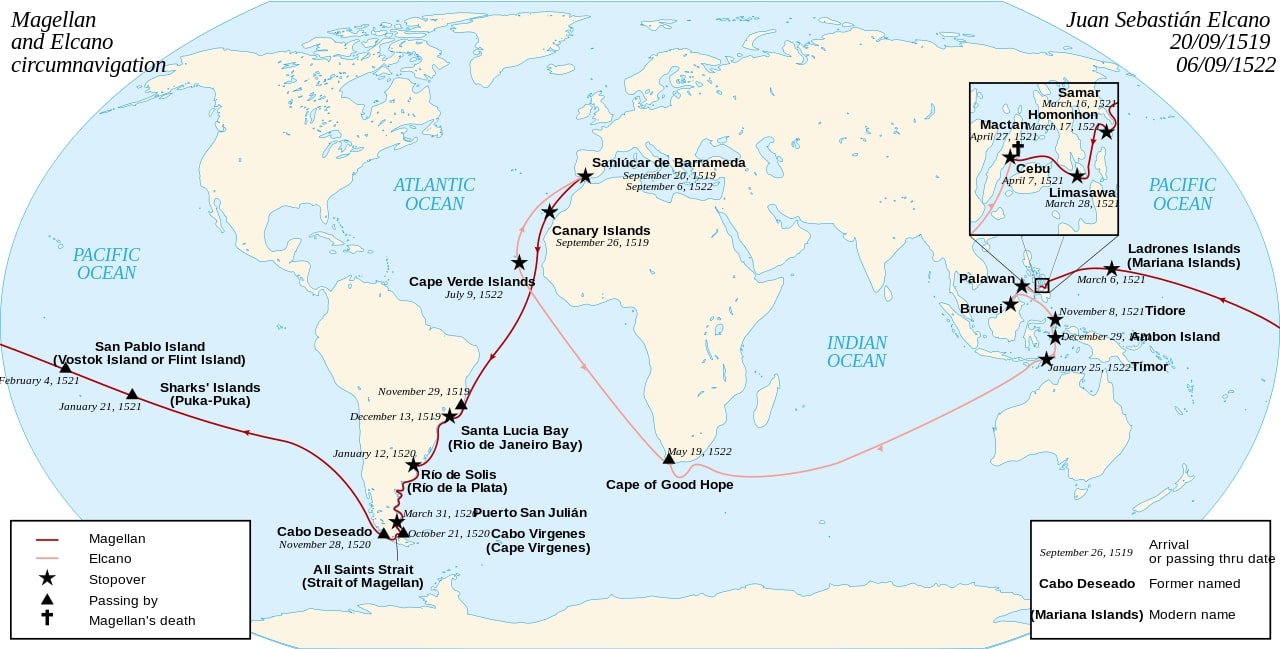

Magellan’s enterprise was of a different quality—open oceans, difficult passages, difficult weather, diseases, discontent, and rebellions within his tripulation. At least one ship and many men were already lost before crossing the passage that lead them to the Pacific. Once in the Pacific, they encountered new challenges, new dangers, more diseases, more deaths, and conflicts with local powers. They were pioneers in traveling regions and areas unknown to Europeans until then, and they did this with relatively primitive tools.

How did the completion of the circumnavigation shape the rest of the 16th century?

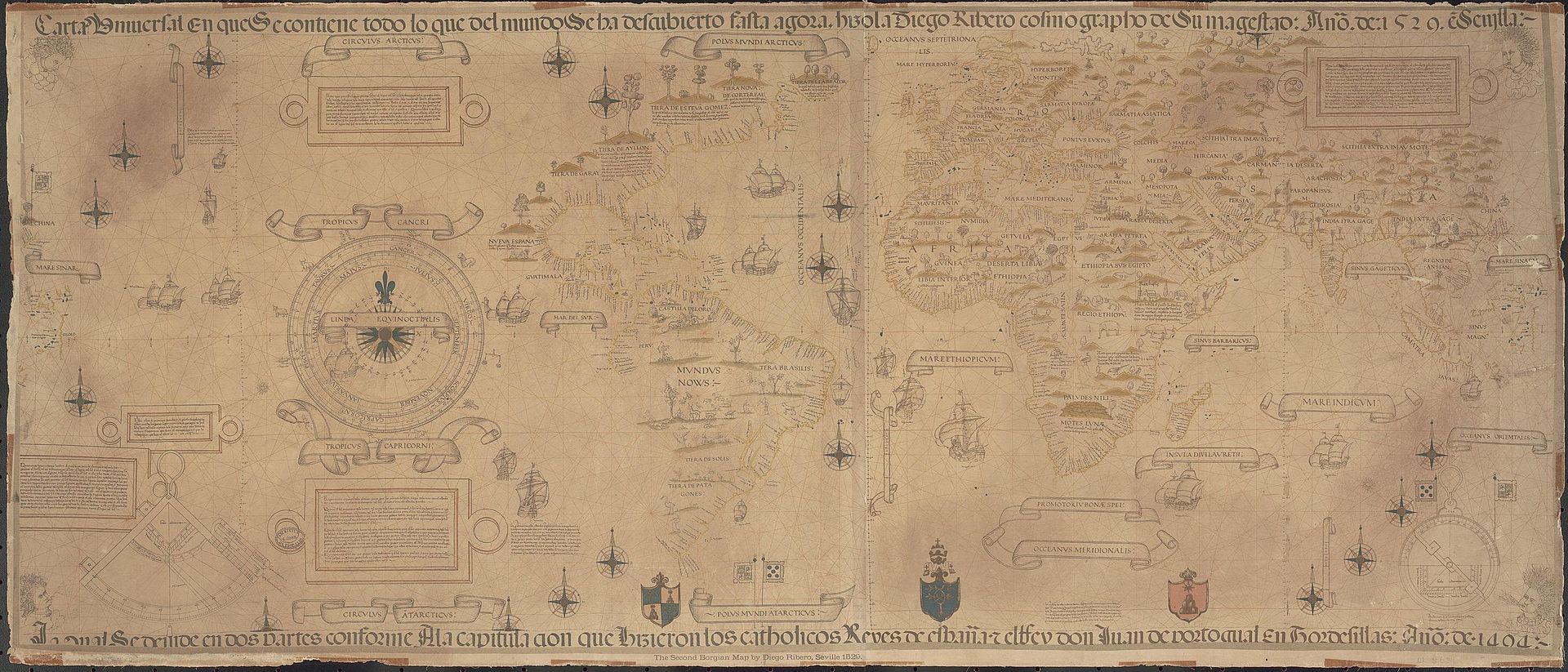

Magellan’s voyage definitively demonstrated that the globe was round, and in reflecting about this voyage, some geographers started to better understand the globe, the various regions of the world. The ‘Universal Map’ drawn by Diogo Ribero in 1529 is clear proof of this.

But these were the unintended consequences of Magellan’s voyage. His was not a scientific expedition, it was a commercial and political expedition, an intent by the Spanish monarchy to enter into the wealthy Asian trade, dominated until then by the Portuguese. Magellan was a sailor, a man serving a king, not a geographer or a scholar. He wanted to discover a route that gave the Spanish monarchy economic power and political influence, but he was not interested in the advancement of geography, or science. He never wrote any treatise about the geography, or the world—mapmakers did that. He was thinking and acting as a man of state.

The real consequences of his voyage were economic and commercial: It allowed the Spanish to establish commercial routes between its colonies in the Americas and the territories they ended controlling in Asia—like the commercial route between the Philippines and Acapulco in Mexico, ‘the Manila Galleons,’ which lasted for more than two centuries. It also accelerated the connections between the various regions of the world.

By the mid-1500s, as a consequence of Magellan’s voyage and many others after him, Europeans became aware that Spanish and Portuguese explorations had ushered in the first period of globalization in the history of humanity. As the French writer Louis Le Roy wrote in 1577, thanks to these voyages and expeditions ‘all humans can now exchange commodities with one another and provide for each other’s dearth, like residents of one city and one republic of the world.’