It was toward the end of their 7,300-mile journey across 23 states, on a quest to interview young adults about how the pandemic has changed their lives, when the two University of Pennsylvania students were faced with a decision: Should they go to the high school prom in Circleville, Utah?

Yes, of course they should, and they did, at the invitation of a local farming family, joining most of the town, population 600, that spring evening.

The prom was one of dozens of unexpected experiences shared by seniors Max Strickberger and Alan Jinich—best friends and Penn roommates who grew up on the same street in Chevy Chase, Maryland—during their journalistic endeavor.

They traveled the country seeking the stories of a diverse range of people, 18 to 25 years old, to create an archive of the pandemic experience. The resulting website for that archive, Generation Pandemic, will feature about 20, 1,500-word, oral history narratives and podcasts drawn from the interviews, photos, and videos they gathered on their journey. They also have a Generation Pandemic Instagram page.

“This is already such a precarious time in our lives, now exacerbated by the pandemic, and we wanted to capture a segment of what that would be like for other Americans our age,” Strickberger says. “We wanted to cover individual stories that could illustrate particular experiences from this year that we thought could be lost during a time of rapid change.”

Strickberger is an English major with a concentration in creative writing and Jinich a neuroscience major and English minor. Both, in the College of Arts and Sciences, are back on campus this fall for their senior year.

Faced with another semester of virtual courses this past spring, they decided to take a chance and take the semester off from their Penn classes to pursue their Generation Pandemic project. But they prepared with Penn professors and kept in touch with them along the way.

“I wanted to do something. I felt like I was living in history and I wanted the chance to capture any part of it or play a more meaningful role in what history was like for me and for people of our age,” Strickberger says.

Jinich, a photographer, says he wanted to pursue a long-term, creative project, and get out of the bubble of reading everything through his phone screen. “We wanted to work on something together and so we decided, just two weeks before the spring semester started, to take it off and take on this project,” Jinich says.

Preparing and planning

They started by reaching out to several Penn faculty, including Kathy Peiss, history professor, Margo Natalie Crawford, English professor, Jean-Christophe Cloutier, associate professor of English and comparative literature, and writer Sam Apple, who teaches creative writing.

“It was a new world to us, this world of oral history and journalism. So we wanted to learn about it from an academic perspective to prepare,” Strickberger says.

He had taken Peiss’s class, Modern American Culture, and she agreed to collaborate on this project, creating an eight-week syllabus of readings and meeting with them virtually once a week.

They read several classic texts and recent writings included Studs Terkel’s “Working,” first-person interviews with a variety of workers in the 1970s, and “Hard Times,” first-person accounts of daily life during the Great Depression. “We wanted to do that kind of oral history with personal narratives, but specific to our age and about the pandemic,” Strickberger says. “We wanted the peoples’ stories to speak for themselves.”

Peiss says she chose readings to help them think about how to position themselves as interviewers, how to relate to new people and places, and how to deal with their own assumptions.

“To me it was a kind of classic American story of going on the road and learning about your country. And they really were engaged, not only with the people they met, but also with seeing parts of the country they’d never seen before,” Peiss says. “It really was a work of discovery, and of connecting to people who are in their own age group but who have lived very different lives than they have. I think what they’re doing is inspiring.”

They also often spoke with Cloutier, who had Strickberger in his courses, Jack Kerouac & Postwar Counterculture and Post 45 American Literature & Film.

“I see some tendrils of Kerouac and the Beat Generation in Max and Alan’s project,” Cloutier says. “They’re combining forces to try to understand and diagnose a moment in time for a certain generation. And of course they’re going on the road—they seek actual encounters.”

Strickberger and Jinich had taken a creative writing course, Extreme Noticing, taught by Apple, who suggested they read Eli Saslow’s column “Voices from the Pandemic” in The Washington Post. “We read it and realized that is exactly what we wanted to emulate,” Strickberger says. “We wanted to do more serious interviews that aren’t just a snippet of someone’s life, but a more sustained engagement with what was going on in a particular moment during the pandemic.”

Even though they were not officially enrolled in Penn classes, Cloutier says the pair were continuing to learn from their Penn experiences. “I see it as a kind of extended research project that involves field work. And I’m proud of what they've been able to achieve,” he says. “I see in them a kind of pioneering drive, to want to do something in the world, to immerse yourself in that experience, and to kind of shake off your own comforts or your own kind of prescribed path.”

Hitting the road

They used a demographic GIS map, Social Explorer, to determine a route with geographic and socioeconomic diversity, down through the Deep South, out west through the Rockies, and back through the Midwest.

“We were looking for different kinds of places, big cities, tiny towns, places with racial, ethnic, political, religious diversity,” Jinich says. “We used that to inform a long list of potential stops that we could hit.”

The pair set out on April 8, both fully vaccinated against COVID-19, driving Jinich’s mother’s SUV, with a plan to stay with friends and family in combination with Airbnbs and car camping. The first week was loosely planned, and the rest unfolded as they went along.

“It felt luxurious to get on the road and drive 250 miles when we had just spent the last 12 months in our bedrooms,” Jinich says.

“It was the best feeling. Wake up one day and we’re driving 10 hours,” Strickberger says.

The first day they made it to Chattanooga, Tennessee and conducted their first three interviews, prearranged through a friend from Penn. But after that, they would pull into a new place and start asking strangers who looked like they were in the age range if they would be willing to be interviewed.

“I’d basically say ‘Hi, my name is Max. I’m working on an oral history project, talking to young people all over the country. We just got into the area. We’d love if you’d be interested in taking some time to speak with us.’” Strickberger says. “And they’d tell us no, or yes, or I can but not right now, or I’m not in that age range but try the church down the street, or the hotel, or the grocery store.”

The first big test was in Greensboro, Alabama, a town of about 2,500. No one would talk with them, but then a grocery store manager agreed to help and went up and down the aisles asking people their ages, introducing them. “It felt really good when we could get people to speak with us, because every time we got to a new town, it was just like: restart,” Strickberger says.

Their goal was to get a total of 50 interviews in six weeks, and they conducted 80, some as short as 15 minutes and others lasting for several hours, with the average being about an hour and a half. They did most together but would frequently split up and do some alone. In pursuing the story of Jesus, a cattle rancher on the Texas-Mexico border, Jinich’s interviews spanned several days.

“Towards the end we were able to say ‘We’ve spoken with 70 people and we’ve traveled to 20 states and we’d love to include you,’” Jinich says. “It felt like it had more weight to it, and felt like an accomplishment.”

Approach to an archive

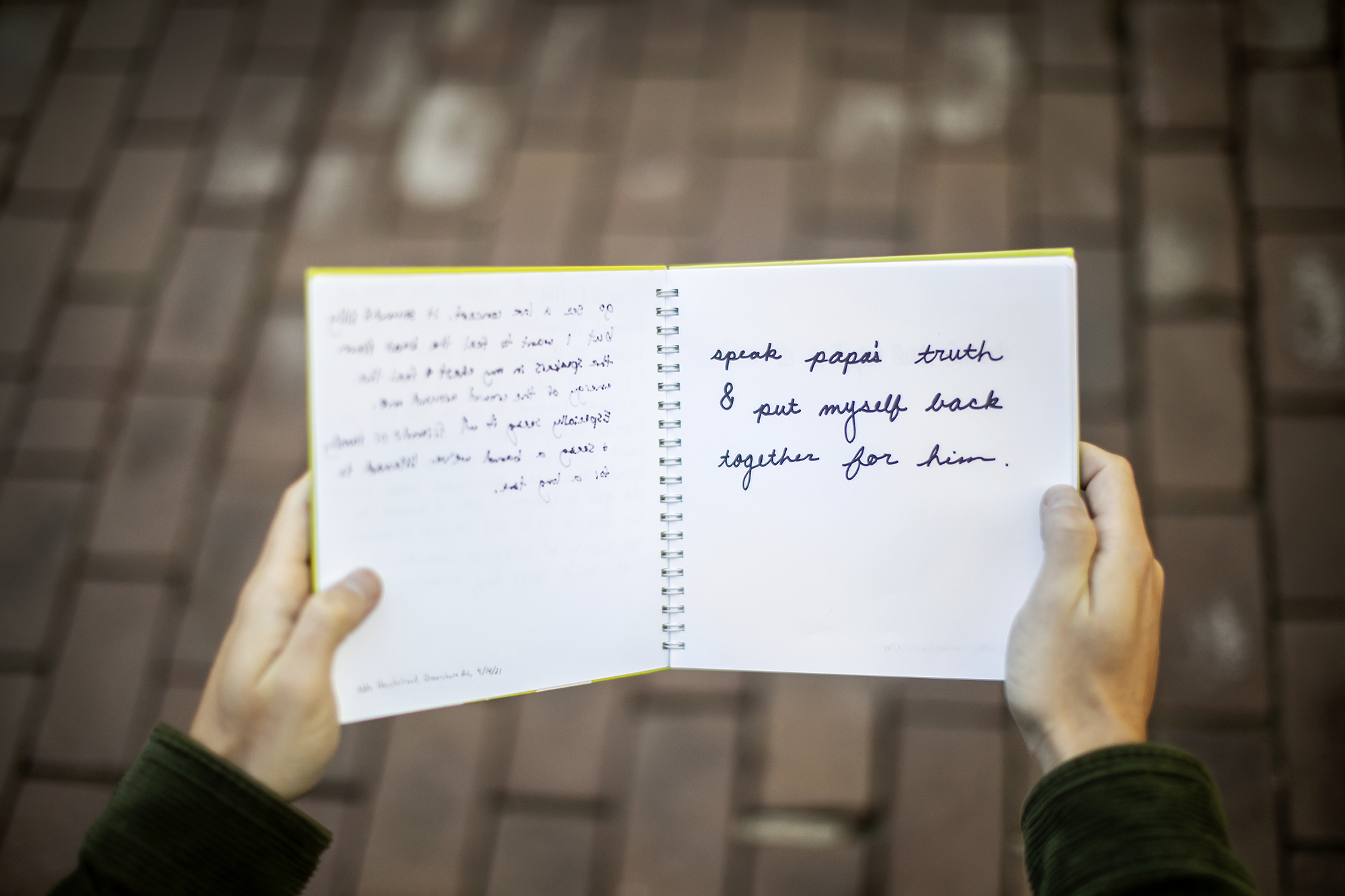

They asked each person to write in a notebook the answer to the question: “After the pandemic I want to…” Strickberger says he got the idea from a conversation with novelist Jennifer Egan about the project. The two stayed in touch after he took her course, Self, Image, Community: Studies in Modern Fiction, when she was an artist-in-residence in 2019.

The pair spoke with Egan the night before the trip. “She got us interested in this topic of futurity, looking down the road,” he says. “We had every single person we interviewed fill in the blank, in their own handwriting. We wanted something tactile, something more physical in that way. And that ended up being a really meaningful part, seeing young people writing while envisioning what life would be like after the pandemic.”

Peiss says this type of first-person archive is important for historians. “I think an archiving and interviewing project like this will be looked at many decades hence,” she says. “We'll want to know what this time was like, just as people in the 1930s were trying to understand the Great Depression by interviewing people, by photographing them, and creating a record of that experience that we still draw upon today.”

A range of stories

Early on they decided not to seek out interviews with people who were full-time college students like themselves, and instead looked for people who represented other experiences.

Some stories they didn’t realize they needed until they found them, like Faith, a woman they encountered in Utah who told them she was the first person in her county to contract COVID-19. “She spoke with us about being treated like a pariah, about how rumors were spreading about her family and herself in this small town,” Strickberger says. “Once she got out of quarantine, everyone kept at a distance until the sheriff hugged her.”

They went to many small towns, but also to several cities. In Chicago they were rejected by everyone they approached in Chinatown. “Then all of a sudden, I hear this guy on the street speak Spanish,” Jinich says. “So I started speaking to him in Spanish and we just bonded as Mexicans. I started interviewing him about his job and it ended up being my favorite story of the entire trip.” Fernando’s was one of several interviews that Jinich conducted in Spanish, his first language.

One of the most powerful interviews was with Sharon, a young woman in Santa Fe who came back to live with her mother and older brother and his baby during the pandemic, struggling to help them while trying to keep up with college classes. Her brother was addicted to heroin and her mother, who did not speak English, was trying to navigate the court system for custody of the baby.

Cloutier says even though the project focused on a particular generation, stories like Sharon’s make the archive “a much wider and richer portrait of the American scene right now, glimpsing the experiences of other generations,” he says.

“Through the daughter, you glimpse the mother. As with any personal archive, there’s always a multiplicity of lives that leave a trace,” Cloutier says. “Reading the testimonies you immediately see the array, the range of people that they’ve been able to meet, and how Max and Alan have allowed them to tell their own stories, which I really, really admire.”

Prom?

Patience and perseverance combined with chance and a little luck as they stopped in Circleville, Utah. They spoke with a few skeptical construction workers on Main Street and decided to move on to the next town, but then they passed a sign for a dairy farm. No one in their age range was there, but the person there suggested they go on up to the Dalton’s farm.

After stopping at a little café for directions they found the farm, and two young people outside, who turned out to be Tyler and Jay Dalton. But they didn’t want to be interviewed.

“We just kept the conversation going and I finally said, ‘We’re basically doing the interviews right now,’ and then they allowed us to record our conversation,” Strickberger says. “Once we sat down, the interview went on for hours. By the end of it, Tyler and Jay introduced us to their whole family.”

Next came a four-hour tour of the turkey farm, and Jay and his wife invited them for dinner. Jay’s parents then invited them to Sunday lunch. “And later they invited us to the high school prom, because everyone in the town goes to the prom—moms, dads, aunts, uncles, everybody,” Jinich says.

Coming back

The pair arrived back in Philadelphia on May 17, the day of Penn’s Commencement, and reconnected with many of their friends. During the summer they edited the narratives and photos, working with Penn alum Daniel Fradin to build their website.

“I had no idea that I would love interviewing people so much. We loved transcribing these interviews and editing down these stories. I found I really love this work,” says Jinich. “I study neuroscience and I’ve been undecided as to what I want to do after school, and now I’m considering work that involves writing and interviews.”

The same is true for Strickberger. “I didn’t know how meaningful I would find it,” he says. “It was really energizing to be out there and trying to find someone who was generous enough to share a part of their life with us.”

As they settle into their senior year at Penn, they are continuing work on the Generation Pandemic archive. Cloutier sees many possibilities. “Who knows how this will percolate in the long run for them: exhibitions, photographs, maybe works of non-fiction down the road? Maybe even a novel based on these experiences? Maybe an archive that will go on to inspire others and launch new endeavors?” he says. “Who knows? It’s exciting.”

Jean-Christophe Cloutier is an associate professor of English and Comparative Literature and Undergraduate Chair of Penn’s English Department in the School of Arts & Sciences.

Margo Natalie Crawford is a professor of English and the Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Professor for Faculty Excellence and the director of the Center for Africana Studies in the School of Arts & Sciences.

Kathy Peiss is the Roy F. and Jeannette P. Nichols Professor of American History in the School of Arts & Sciences.