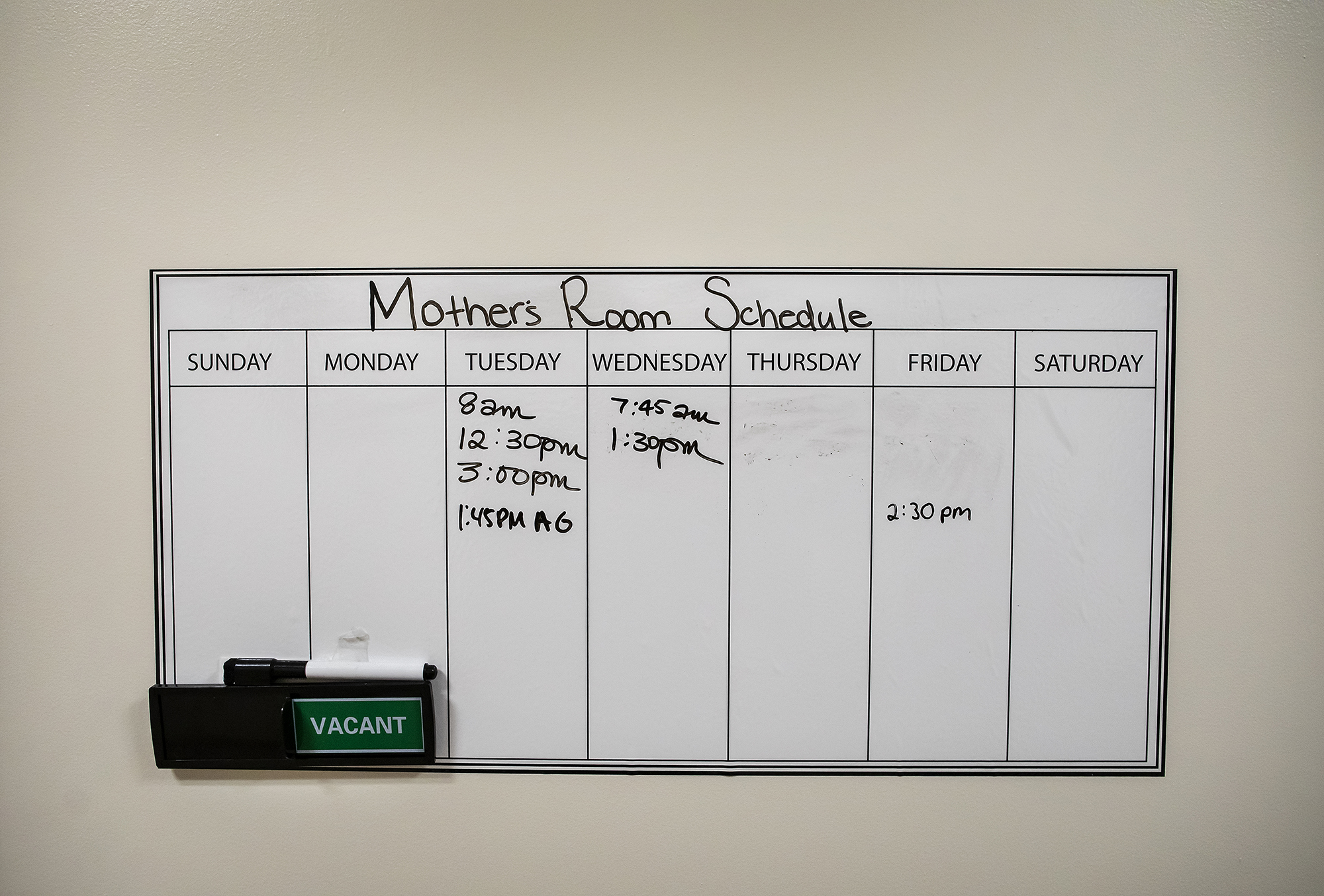

In the Nursing Renewal Suite at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, just down the hall from the cafeteria, a multi-user room allows three breastfeeding mothers to pump at once. The room has a mini-fridge for storing milk, and moveable screens offer privacy between the chairs.

It’s one of the most popular pumping spaces at the hospital, used nearly 5,000 times over the course of a single year. Now, after a two-year wellness initiative by Penn Medicine focused on improving lactation support, breastfeeding mothers have even more options.

The effort stemmed from the results of a crowd-sourcing campaign from the Center for Health Care Innovation and the Penn Medicine Faculty Well-Being Committee; better lactation support topped the list of hundreds of faculty priorities. “From both men and women, it was a big concern,” says Lisa Bellini, vice dean for academic affairs at the Perelman School of Medicine. “People wrote in all sorts of anecdotes about how they didn’t have the facilities to pump, how it took too long, how they had to go too far, how it was very disruptive to productivity.”

With that knowledge in hand, Penn Medicine took action and in just two years more than doubled the number of lactation spots available to its faculty, staff, and trainees; every one of 56 stations is now outfitted with a hospital-grade pump. Such spaces are also being added to the designs for any new construction, and Penn Medicine has updated its policy regarding breastfeeding and pumping in an attempt to normalize the activities and offer greater support.

Since 2014, Dare Henry-Moss had been researching how workplaces could better support mothers. When the campaign began, she was earning her master’s of public health from Penn but was also a full-time Penn Medicine employee who was pumping for her second baby. Once she learned that lactation support was the winning priority of the campaign, she approached the wellness committee with an idea: For her capstone project, she wanted to develop a recommendation plan for improving lactation support for the Health System, including conducting a needs assessment that could guide standards for such spaces.

“Hospitals are really complex places from a workplace perspective. There are a lot of different jobs. People are employed by different entities and they may all have different needs,” explains Henry-Moss, who is now an adjunct fellow at the Center for Public Health Initiatives. “We thought a needs assessment was important. We wanted to make sure we got the improvements right.”

With the blessing of the committee and with guidance from Penn Nursing’s Diane Spatz, Henry-Moss developed the survey and started recruiting Penn Medicine employees who had pumped at work within the past five years. In total, 151 participants had spent an average of 10 months pumping, some for one child, others for multiple children. Seventy percent of them had used one of the hospital’s dedicated lactation rooms, and 72 percent had previously used a hospital-grade pump.

One-third worked in research and administration, a third were nurses, and the rest were either physicians and medical students or allied health or clinical support staff. They responded to questions like ‘How easy or difficult has pumping been for you?’ and ‘Where do you store your milk?’

Their answers were telling; participants wanted access to a nearby lactation space, one they didn’t have to wait to use when they arrived. They didn’t mind if that meant a suite was multiple occupancy, and they wanted it close by.

Such findings didn’t surprise Spatz, who runs the lactation program for the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “More women today are breastfeeding than ever,” she says. “Right now, still all the onus is put on the mom to figure it out. It’s really all about time. How do you manage both having a really busy work schedule and also being a breastfeeding mom?”

Henry-Moss brought what she’d found back to Bellini, to Jennifer Brady, UPHS manager of employee health and well-being, and to the rest of the committee working on making these system-wide changes. Bellini decided on a two-part roll-out. During Phase 1, which took place between March and August of 2017, the team catalogued all existing rooms and added to hospital-grade pumps that are more efficient and prevent breastfeeding mothers from having to transport their own. Some of the rooms also received additional seating and dividers to accommodate multiple women at once.

“Phase 2 was really looking at the space that didn’t have any rooms,” Brady says. “Across the system, where are we missing lactation space? There was a lot of opportunity.”

At the same time, UPHS revised its policy regarding breastfeeding and pumping to better match the University’s and to include language about allowing such employees reasonable break time in an environment supported by their supervisors and managers. Bellini also created an eight-minute video on the subject directed at leadership and focused on normalizing and supporting breastfeeding and pumping.

Though the Health System has mostly completed the second part of the plan, Brady says they’re still making new spaces available when a previously unknown need arises.

“We’ve made a ton of progress, and the feedback has been amazingly positive,” Bellini says. “We’re pretty proud.”

The team published a paper in the journal Breastfeeding Medicine on the results of the needs assessment Henry-Moss led, and she and Spatz continue to think about whether their findings could apply to other settings. The general concepts—needing a nearby, private, available space—certainly do, and with more than 80 percent of American women initiating some breastfeeding after they give birth it certainly affects a large swath of the population.

“It would be great if we actually got what people need. Wouldn’t that be amazing?” Henry-Moss says. “The more evidence that you can put out there about what is really needed makes such a difference.”

Dare Henry-Moss is an adjunct fellow at the Center for Public Health Initiatives. She was formerly a research coordinator for the Perelman School of Medicine and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and earned her master’s in public health from the University of Pennsylvania in 2017.

Lisa Bellini is vice dean for academic affairs, a professor of medicine and vice chair of education and inpatient services for the Perelman School of Medicine Department of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Diane Spatz is a professor of perinatal nursing and the Helen M. Shearer Professor of Nutrition at the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing. She is also a nurse researcher and manager of the lactation program at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Jennifer Brady is the manager of employee health and well-being at the University of Pennsylvania Health System.