nocred

RESEARCH/Card gambling among teenage boys and young men is growing rapidly, and that’s a cause for worry, says this public policy researcher.

With March Madness in full swing, many are finding themselves drawn into office pools or logging onto the online betting bonanza that now accompanies the three-week college basketball tournament. For most, it’s a once-a-year foray into the high thrills world of betting. For others, it’s one more opportunity to indulge a regular gambling habit.

And, as Dan Romer has discovered, many habitual gamblers are below the age of 22. For the last four years Romer, who directs the Annenberg Public Policy Center’s Institute for Adolescent Risk Communication, has overseen a wide reaching survey on risky behavior. The National Adolescent Risk Survey of Youth (NARSY) annually polls about 900 youngsters between the ages of 14 and 22 about their involvement with tobacco, alcohol and drugs, as well as gambling.

Romer says while other national surveys, such as the Michigan Youth Risk Behavior Survey, track drug use, no one has followed gambling. “And over the four years,” he adds, “we’ve watched this thing mushroom.”

The most recent NARSY numbers, gathered over the summer of 2005, showed a 20 percent increase in monthly card gambling among young people compared to the previous year. Based on the latest estimates, says Romer, 2.9 million 14-to-22 year-olds are gambling on cards on a weekly basis and more than 80 percent of those are young men.

Gambling has only recently been added to the list of risky behaviors for adolescents. When Romer put together a conference on adolescent risk in 2002, soon after his institute was launched, gambling was not yet considered a serious health threat to U.S. youth. At that time, says Romer, it was thought to be a side issue, and though he brought in a speaker from Britain to talk about the escalating problem there, many were not convinced the U.S. faced a similar danger on this side of the Atlantic. Back then, says Romer, “We thought the problem would be lotteries and casinos opening. We didn’t see the poker craze coming, and then the web.”

High school and college students themselves rarely perceive their gambling as a problem. Smokers, says Romer, will talk about how they’re planning to quit, whereas young gamblers see their preoccupation as a social activity or harmless hobby. “People don’t realize they could lose and really get in a hole,” says Romer, who has received emails from a recent undergraduate who lost tens of thousands of dollars.

With online gambling on the rise, many of these young gamblers are doing it alone, racking up debt in their bedrooms after school and becoming ever more addicted. Card gambling, says Romer, leads to other kinds of gambling, too, like horse racing and sports betting, and it also tends to go hand in hand with tobacco and alcohol use leading, potentially, to a life destroying trio of addictions.

Since online gambling is illegal—though many gambling advocates argue the 1961 wire act is ambiguous—sites such as partypoker.com and absolutepoker.com are all based offshore in places like Gibraltar or the Isle of Man. Though the sites state that players must be at least 18 years old, a young person merely has to attest to that fact with a click to be registered.

Romer’s goal is to publicize this disturbing trend and create more awareness of the problem. Beyond that, he sees education as an important step. “Everyone who’s addicted and paying the price says, ‘No one told me.’” And though it’s true that only a small percentage of young gamblers will become addicted, Romer says to not talk about the risk is hypocritical when so many programs and educational campaigns address drugs and alcohol. What may hamper efforts, he concedes, is that while people “can see how drugs can mess up your brain, they don’t see how a behavior like gambling can.”

High schools and universities—including Penn—are “torn about whether to be more proactive,” he says, though educational programs have now been developed for middle school children in Delaware. “It would be good to know if they work,” says Romer. “We need to educate our students.”

nocred

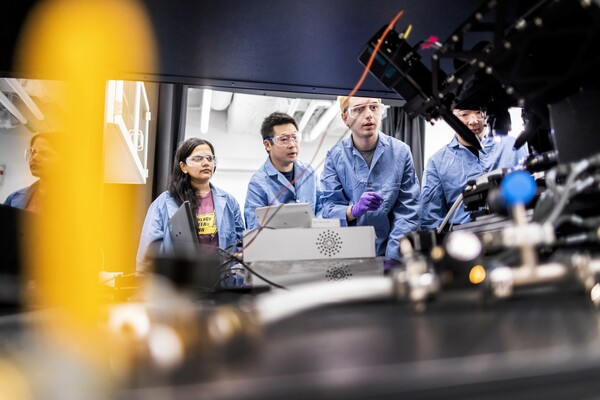

The sun shades on the Vagelos Institute for Energy Science and Technology.

nocred

Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

nocred