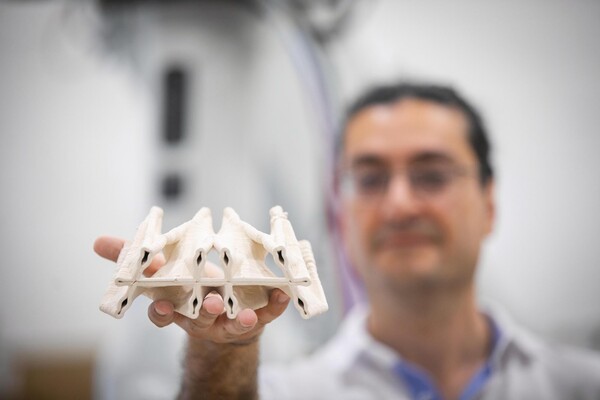

The Polyhedral Structures Laboratory is housed at the Pennovation Center and brings together designers, engineers, and computer scientists to reimagine the built world. Using graphic statics, a method where forces are mapped as lines, they design forms that balance compression and tension. These result in structures that use far fewer materials while remaining strong and efficient.

(Image: Eric Sucar)