Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

Penn Medicine researchers have developed a better way to assess and diagnose psychosis in young children. By “growth charting” cognitive development alongside the presentation of psychotic symptoms, they have demonstrated that the most significant lags in cognitive development correlate with the most severe cases of psychosis. Their findings are published online this month in JAMA Psychiatry.

“We know that disorders such as schizophrenia come with a functional decline as well as a concurrent cognitive decline,” says Ruben Gur, PhD, director of the Brain Behavior Laboratory and professor of Neuropsychology at the Perelman School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania. “Most physicians have a clinical basis from which to assess psychosis, but less idea as to how to best assess and measure a decline in cognitive function. To make this easier and to aid in early diagnosis and treatment, we created ‘growth charts’ of cognitive development to integrate brain behavior into the diagnostic process.”

Psychosis is a severe mental illness, characterized by hallucinations, delusions, social withdrawal and a loss of contact with reality. Genetics and environment, including emotional or physical trauma, can both play a role in its development.

The Penn researchers assessed the brain behavior of a cohort of about 10,000 patients between the ages of eight and 21 at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia from November 2009 to November 2011, including 2,321 who reported psychotic symptoms. Of those, 1,423 reported significant psychotic symptoms, 898 had limited psychotic symptoms, and 1,963 were typically developing children with no psychotic, mental or any medical disorders.

Researchers administered a structured psychiatric evaluation, looking for symptoms of psychosis, anxiety, mood, attention-deficit, disruptive behavior and eating disorders; for the younger children, independent interviews with their caregivers were also conducted. The team also administered 12 computerized neurocognitive tests to evaluate each child’s brain development across five domains: executive function, testing abstraction and mental flexibility, attention and working memory; episodic memory, testing knowledge of words, faces and shapes; complex cognition, evaluating verbal and nonverbal reasoning and spatial processing; social cognition, looking at emotion identification, intensity differentiation and age estimation; and sensorimotor speed, to understand the workings of their motor and sensorimotor skills.

The results were analyzed to predict chronological age for each child.

Click here to view the full release.

Lee-Ann Donegan

Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

nocred

nocred

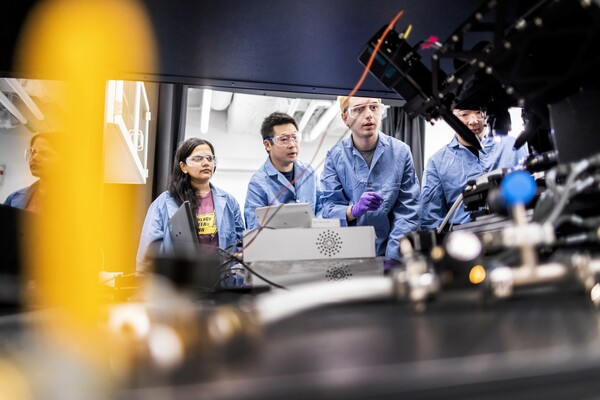

(From left) Kevin B. Mahoney, chief executive officer of the University of Pennsylvania Health System; Penn President J. Larry Jameson; Jonathan A. Epstein, dean of the Perelman School of Medicine (PSOM); and E. Michael Ostap, senior vice dean and chief scientific officer at PSOM, at the ribbon cutting at 3600 Civic Center Boulevard.

nocred