Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

What if with the click of a button, a clinician could improve and personalize a patient’s treatment for a mental illness like post-traumatic stress disorder, depression or panic disorder? That’s the goal of a new data tournament created by Robert DeRubeis and Zachary Cohen of the University of Pennsylvania that will start in October and run through March.

“We can do a better job of matching a person with the treatment that’s going to work well for them, that’s not much more than they need in terms of time and effort and that is much more likely to help them,” said DeRubeis, the Samuel H. Preston Term Professor in the Social Sciences. “We’re hoping that this brings the overall efficiency of mental-health treatments up a notch or two, at a very low cost.”

For the tournament, nine teams from universities and labs across the country and the world will receive data from 4,000 patients treated in northern England through the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies, or IAPT, program during a specific four-year period. An additional randomly selected 2,000 patients from that same time frame will be set aside to act as a test sample later.

Teams will then aim to build a predictive model that indicates which patients should start with low-intensity treatment and which should begin with high-intensity treatment. The output must accurately reflect the current IAPT patient breakdown, in which approximately 27 percent start in the high-intensity bucket.

The idea dawned on the researchers after hearing Barbara Mellers, a Penn Integrates Knowledge Professor, discuss The Good Judgment Project, a four-year forecasting tournament that asked groups to predict answers to 500 political questions. The Penn team, which she ran with PIK Professor Philip Tetlock, won and in the process discovered what they came to call superforecasters, ordinary people whose combined predictive abilities became more powerful than highly trained intelligence-community analysts.

Cohen thought the same design could be applied to mental health, where professionals all looking at the same dataset try to predict the same outcome and then learn from each other.

“The model we would generate from that would be the best model,” he said, “and it would have an immediate impact on the system in which we’re building it.”

MQ, an organization that focuses on transforming mental health and quality of life through research, funded the tournament through a data science research award. The winning algorithm could, in theory, be implemented almost immediately, Cohen said.

“The data that we’re using is a set of standard data collected on every patient across the IAPT system, and that’s millions of people,” he said. “The data are available; the system is available. They wouldn’t have to treat new patients but rather start allocating their resources more intelligently.”

Ultimately, that’s the point of the tournament, DeRubeis said, and it won’t take a whole lot to make an impact.

“If there are 100 people coming to a clinic, all you need is to make a better decision about 10 of those people,” he said. “That helps both kinds of individuals” — those getting high-intensity treatment who don’t need it and those not getting it who do — “and it helps make the system more efficient so that more people can be cared for because now you’re not expending resources ineffectively.”

Determining what would constitute the winning algorithm took some nuanced thinking. The winner couldn’t necessarily be the team that made the most people healthier because theoretically that could happen by pointing those with the worst prognosis to the low-intensity treatment. In other words, they are in such a state that high-intensity treatment can’t help so why bother trying. And that would skew the results. So the researchers determined that the winning model had to be based on prognosis.

“Instead of saying who will have the most benefit of the stronger treatment over the weaker treatment,” Cohen said, “which would optimize the system, you’re only allowed to say who looks like they’re going to need the strongest treatment, who has the worst prognosis.”

DeRubeis and Cohen plan to present the tournament results at the Treatment Selection Idea Lab in June. The first TSIL took place in 2016, hosted by Penn’s School of Arts & Sciences, Penn Medicine and MQ. The winning model could be implemented by IAPT by the end of 2018.

“There really is an excitement around this,” DeRubeis said. “We’re trying to push the envelope as far as we can. How much it will help, how far it will go? We’ll find out.”

Michele W. Berger

Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

nocred

nocred

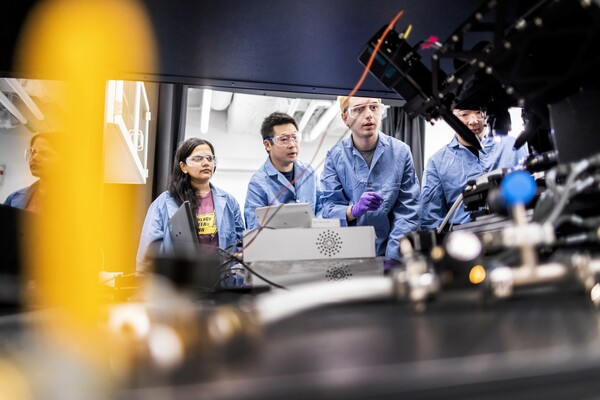

(From left) Kevin B. Mahoney, chief executive officer of the University of Pennsylvania Health System; Penn President J. Larry Jameson; Jonathan A. Epstein, dean of the Perelman School of Medicine (PSOM); and E. Michael Ostap, senior vice dean and chief scientific officer at PSOM, at the ribbon cutting at 3600 Civic Center Boulevard.

nocred