Griffin Pitt, right, works with two other student researchers to test the conductivity, total dissolved solids, salinity, and temperature of water below a sand dam in Kenya.

(Image: Courtesy of Griffin Pitt)

Gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), an inherited disorder that causes loss of night- and day-vision starting in childhood, improved patients’ eyesight within weeks of treatment in a clinical trial of 15 children and adults at the Scheie Eye Institute at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. New results involving a subset of patients from the ongoing trial show that these benefits peaked one to three years after treatment and then diminished. The findings are published today in The New England Journal of Medicine.

In the new study, the research team reports long-term follow-up from three of the earliest treated patients among the initial cohort of 15 patients who received the investigational therapy. The patients underwent extensive tests of their vision and imaging of the retina from baseline beginning prior to their treatment and for up to six years after treatment. These in-depth examinations, which are not likely to be performed in later Phase trials, revealed that this cohort’s vision rapidly improved and slowly expanded and then slowly contracted.

“This study shows that the current therapy doesn’t appear to be the permanent treatment we were hoping for, but the gain in knowledge about the time course of efficacy is an opportunity to improve the therapy so that the restored vision can be sustained for longer durations,” said lead author Samuel G. Jacobson, MD, PhD, a professor of Ophthalmology and director of the Center for Hereditary Retinal Degenerations and Retinal Function Department at the Scheie Eye Institute at Penn.

Mutations in the gene RPE65 cause LCA in about 10 percent of patients. The gene produces a protein critical for vision that is found in the retinal pigment epithelium, a layer of cells adjacent to the light sensors or photoreceptor cells of the retina. In the retina, millions of photoreceptors detect light and convert it into electrical signals that are ultimately sent to the brain. Photoreceptors rely on the RPE65-driven visual cycle to recharge their light sensitivity. They also need RPE65 for their long-term survival. In LCA, the cells eventually die, halting eye-to-brain communication, and with that, the patient’s vision.

Jacobson along with co-investigators Artur V. Cideciyan, PhD, a research professor of Ophthalmology at Penn and William W. Hauswirth, PhD, Professor of Ophthalmology of the University of Florida at Gainesville, first began their gene therapy clinical trial in 2007. In the trial, people with LCA received retinal injections of a virus engineered to deliver instructions to the retina to produce a healthy version of the gene RPE65. Within days of the injections, some patients reported increases in their ability to see dim lights they had never seen before.

In addition to the rapid onset of greater light-sensitivity, the researchers discovered slowly developing changes to another component of vision: Four of the 15 initial patients started relying on an area of the retina near the gene therapy injection for seeing letters. Normally, the fovea with its high density of photoreceptors is reserved for seeing fine details.

Click here to view the full release.

Lee-Ann Donegan

Griffin Pitt, right, works with two other student researchers to test the conductivity, total dissolved solids, salinity, and temperature of water below a sand dam in Kenya.

(Image: Courtesy of Griffin Pitt)

Image: Andriy Onufriyenko via Getty Images

nocred

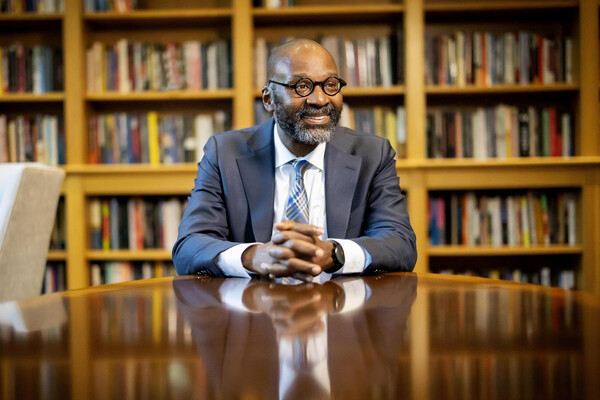

Provost John L. Jackson Jr.

nocred