Image: Aditya Irawan/NurPhoto via AP Images

When asked if increased tensions in the current geopolitical landscape has made her feel a renewed urgency in her work, Penn Integrates Knowledge Professor and international affairs expert Beth Simmons says, “Yeah, I’m starting to feel things are getting a little urgent.”

Simmons has spent decades researching matters that pertain to human rights. Her new agenda is to understand how the walling, crossing, and securing of international borders affects human rights as well as attendant cultural, economic, legal, and moral issues. She recently came to Penn where, with faculty appointments in Penn Law, The Wharton School, and the School of Arts & Sciences’ Political Science department, plus an office in Perry World House, Penn’s new global policy research center, the most impactful aspect of her research—its intersectionality—can help set wheels of change in motion.

But first things first, she says.

“It’s important to do the basic research first, and then build knowledge in ways that merit a role in influencing policy. For example, once we know a little more about what the impetus is for countries to put up border walls, we’ll be in a better position to interpret whether the claims made for them match the effects.”

Her research thus far suggests they do not.

“Countries that are more homogeneous tend to put up the bigger structures at their border crossings.” Even if you control for the wealth of a country, she says, the poorer their neighboring country is, the more likely they are to build a structure to filter traffic and transactions—which suggests economic and cultural tensions more than protecting the citizens from harm.

“It’s interesting that the number of walls along national borders has accelerated in the last two decades—despite the laws, rules, and technologies that allow integration across countries.”

So why are nations backsliding into a feudal mindset when there are global information networks and markets that are impervious to physical structures?

“One reason is that globalization also increases demands to filter what comes and goes. But it is also symbolic,” she says. “Some of it is an expression of people’s anxieties.”

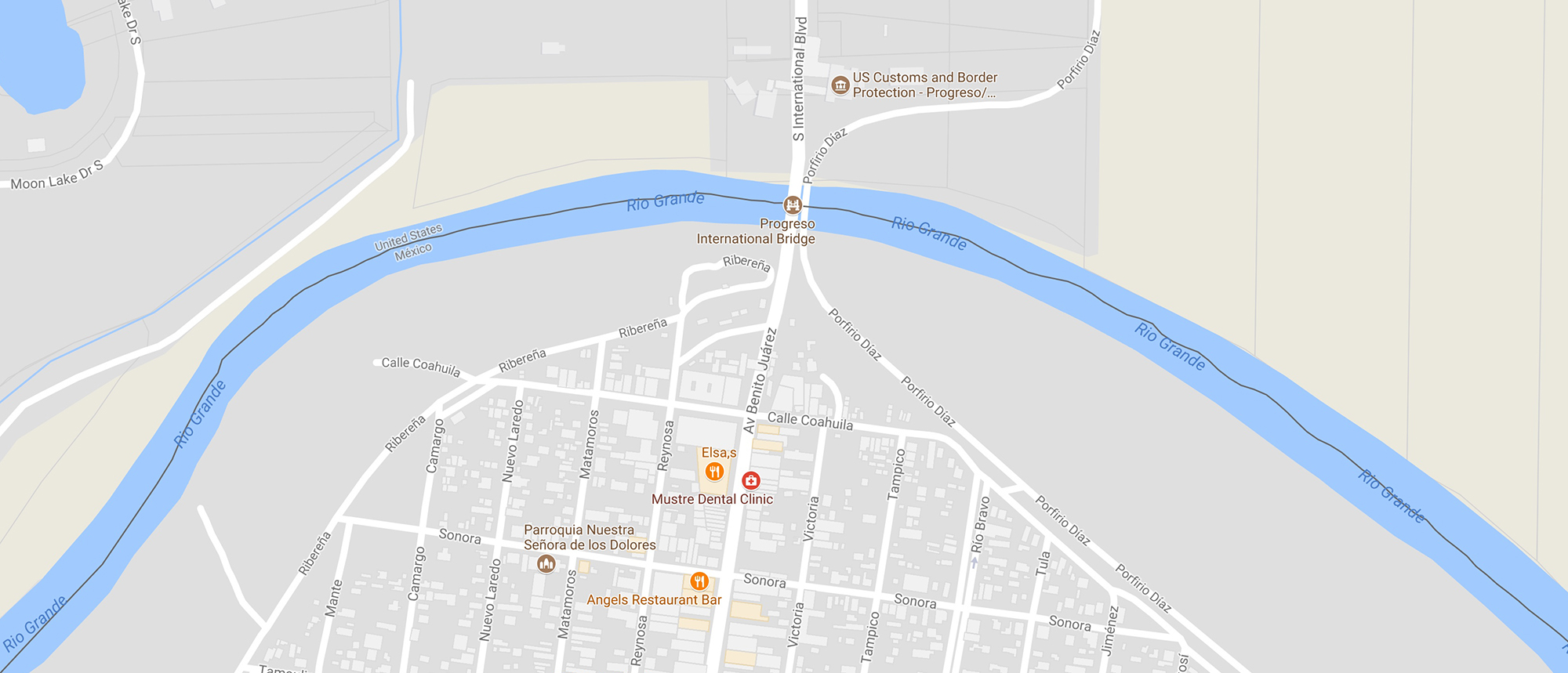

Recently, Simmons started a project on border crossings which involved using Google Maps to look at every place in the world where a major road crosses an international border.

“We created what I think is the first-ever collection of visual images of all the land border crossings in the world. I’m extending that project here at Penn by setting up a research cluster in Perry World House on borders and boundaries in world politics. It’s highly interdisciplinary, involving political scientists, anthropologists, and legal scholars.”

Interdisciplinarity has always been a key signature of Simmons’ work. By joining her extensive knowledge of international relations with the comparative politics expertise of Geoffrey Garrett, who is currently dean of the Wharton School, and Harvard sociologist Frank Dobbin, she contributed to understanding global policy diffusion—the process by which economic ideas and policies spread around the world.

“Our work wasn’t totally unique; it was an adaptation. A lot of good innovations are adaptations of ideas elsewhere in other disciplines. That’s the value of interdisciplinary work—it really can improve ideas and create fruitful research teams.”

Policy diffusion processes suggest that discourse, policies, and institutions used in one country sometimes provide models and are adopted by another country. “So if the U.S. takes a leadership position on human rights, border security, refugee asylum, immigration, and torture,” she says, “the policies you advocate and the words you choose are potentially very important.”

Simmons notes that the words being chosen by the new administration are dramatically different, even if the policies actually put in place are not. One of her current research projects uses a survey experiment to investigate how people are affected by policies advocated by the president that they are told violates one of the United States’ international legal obligations. When people were told the president advocated interrogation practices including torture in order to enhance national security, they were more likely to favor such policies. When they were told such practices violated international legal obligations of the United States, they were less likely to approve.

“What surprised me was that when they were told both that the president advocated such policies and that these were international law violations, respondents were even more opposed to torture than when they were told either statement separately,” Simmons says. “My hypothesis is that if the messages conveyed by the media and nongovernmental organizations consistently reinforce the idea of legal obligation, this is going to lessen the tendency for Americans to say torture is okay, even if leaders say it works. Americans seem a little uneasy when their leaders advocate policies that are illegal.”

Christina Cook

Image: Aditya Irawan/NurPhoto via AP Images

nocred

Image: Michael Levine

A West Philadelphia High School student practices the drum as part of a July summer program in partnership with the Netter Center for Community Partnerships and nonprofit Musicopia.

nocred