Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

Leead Staller, a junior at the University of Pennsylvania, spent his summer working on a research project related to the eventual return of books looted by the Nazis.

Through the Penn Undergraduate Research Mentoring program, Staller, a double major in philosophy and history in the School of Arts & Sciences, worked on a research project that uses the Offenbach Archival Depot as a case study for the American policy and attitude toward the restitution of stolen volumes.

During the early days of the Holocaust, the Nazis often destroyed books and cultural artifacts, but one of Adolf Hitler’s advisors suggested keeping certain important pieces, such as ancient scrolls from the Torah, to document the life of those who were on their way to extinction.

After World War II, the Allies designated the Offenbach Archival Depot, a five-story warehouse located just outside of Frankfurt, as a literary central collection point, where more than 2.5 million looted books could be organized and then returned to their places of origin.

Staller, from Highland Park, N.J., was immediately drawn to the project’s connection between Jewish and American history, both culturally and politically.

“This project invoked powerful emotions, as the Offenbach Archival Depot was an institution dedicated to the restitution and correction of a tattered past,” he says.

As part of the project, Staller translated and summarized works in Hebrew, examined government records and created a timeline that allowed the research team to trace the daily operations of the Depot.

“In those few moments where I put something together or found something that I thought was previously unexplored, I did feel like I was piecing together the past,” Staller says. “I found a mis-dated letter, dated January 1945 when it should have been dated 1946. Discovering that common mistake –- forgetting to update the date after New Year’s, something everyone can relate to -– really made me feel like I was bringing these characters and events back to life.”

He decided to participate in the Penn Undergraduate Research Mentoring program because it was an opportunity to develop skills he plans to use in the future and was a chance to work with one of the University’s top historians, Kathy Peiss.

“Dr. Peiss has been an amazing help and resource,” Staller says. “I’m so appreciative for what she’s given me.”

His research was the first step toward developing a chapter in Peiss’ forthcoming book about the large-scale missions of American libraries, scholars and the military to collect books, documents and other materials in the war years.

“The PURM program offers undergraduates a great hands-on experience,” Peiss says, adding that Staller was able to get a multi-dimensional view of historical research through the use of microfilm and digital documents, along with the personal examination of collections at the Center for Jewish History in New York City and the National Archives in College Park, Md.

He also learned how the books themselves provided important clues, after meeting with librarians at Penn’s Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies and with a curator at the Penn Libraries’ Kislak Center who mapped out the looted collections based on the book stamps photographed at the Offenbach Archival Depot, Peiss says.

“He has been a scholarly partner,” Peiss says. “Leead showed how such basic necessities as coal and transport shaped the fate of these books, and he tried to uncover the truth about five crates of rare Hebrew manuscripts that were illegally shipped to Palestine.”

Staller’s research into the illegally shipped books began with looking for facts related to a rumor that a famous history professor, Gershom Scholem, had stolen rare books from the depot.

“During his visit, Scholem merely set aside five crates of books that were rare or noteworthy. Months later, a Jewish chaplain illegally shipped them,” Staller explains. “Moreover, that chaplain had been in communication with the director of the Depot and seems to have acted in accord with a larger plan.”

Even though he had hoped to find more details through government reports or affidavits, Staller’s trips to the Center for Jewish History and the National Archive yielded no further results.

Staller says the most surprising thing that he uncovered during his research was seeing how much post-war time, money and emotional investment were dedicated to the restitution of books.

“In a society that’s quickly moving to a digital world, it’s important to stop and reflect on the cultural and emotional significance given to the printed word only a few decades ago,” Staller says.

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the people working in the Offenbach Archival Depot were able to return approximately 93 percent of the materials that were looted by the Nazis.

“Research is thrilling at times, especially when you feel that you’ve uncovered a lost piece of history,” Staller says.

Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

nocred

nocred

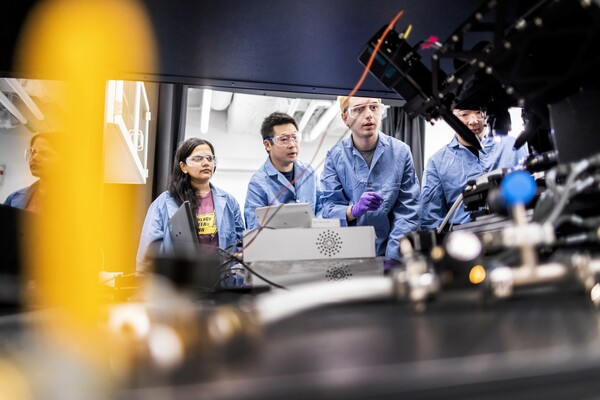

(From left) Kevin B. Mahoney, chief executive officer of the University of Pennsylvania Health System; Penn President J. Larry Jameson; Jonathan A. Epstein, dean of the Perelman School of Medicine (PSOM); and E. Michael Ostap, senior vice dean and chief scientific officer at PSOM, at the ribbon cutting at 3600 Civic Center Boulevard.

nocred