nocred

From Walnut Street, at the corner of 34th Street, a pedestrian walkway cuts a path to 33rd and Chestnut along Hill Square, considered an eastern gateway to Penn’s campus. The walkway is elegant, well-lit, and evidences a thoughtful design for functional aesthetics. But it is actually a significant piece of 21st century art, designed by one of the most influential conceptual artists of our time, and arguably, for the next 100 years.

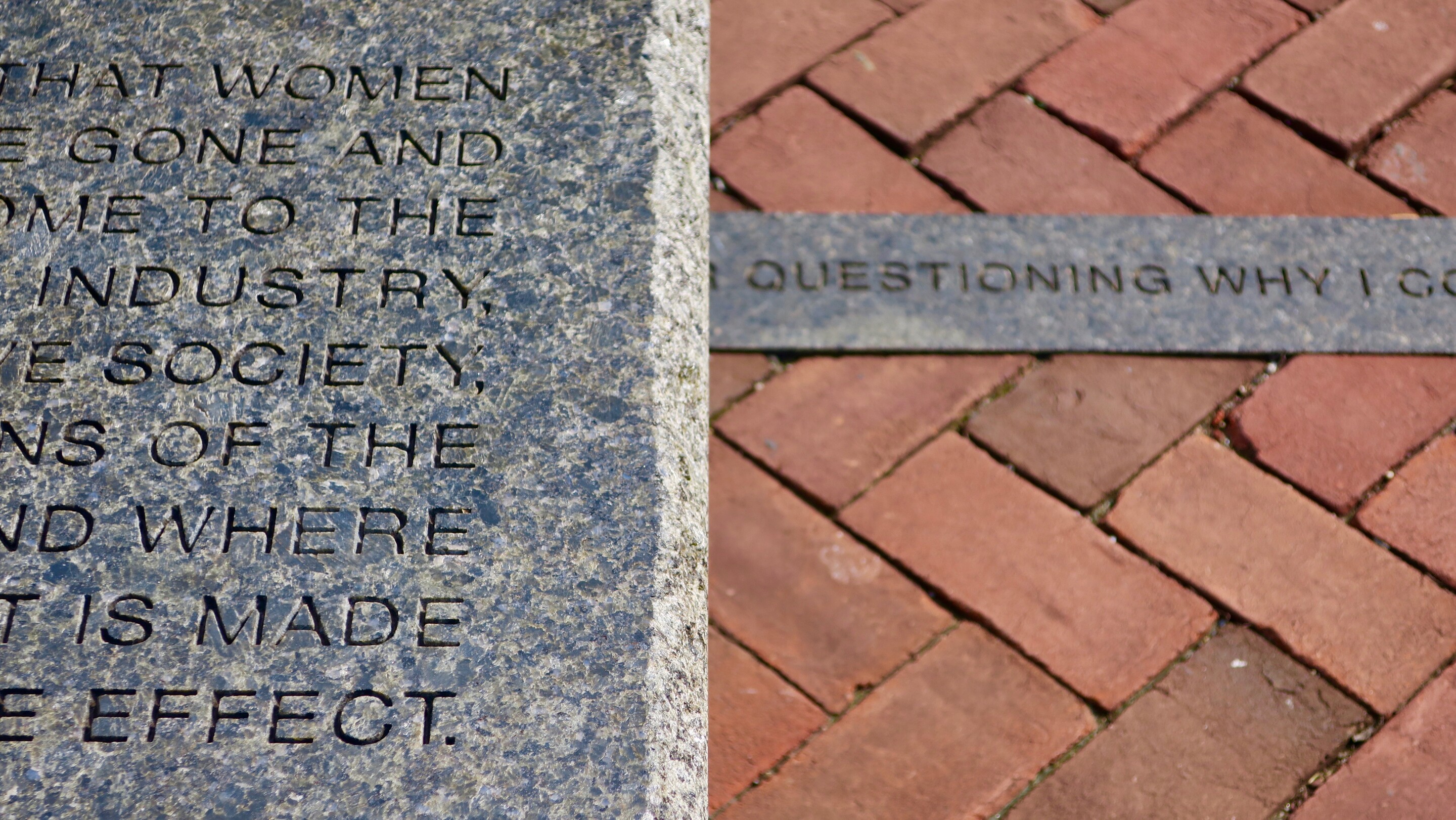

“125 Years” is an art installation designed by Jenny Holzer, and is celebrating its 15th anniversary this month. The University paid homage to 125 years of women at Penn with a celebration in November of 2001. The following year, Holzer was commissioned by the Trustees’ Council of Penn Women, and the project was completed in 2003. The 125-year anniversary dates back to 1876, when Anna Lockhart Flanigan and Gertrude Klein Peirce were the first female students admitted to collegiate courses. They enrolled as special students in the Towne Scientific School (the present-day School of Engineering and Applied Science).

The art installation is comprised of 22 granite benches, the curbing alongside the curved walkway, plus the landscaping and lighting. The focal point meanders, but is centered in text, much like Holzer’s decades of conceptual, largely text-based art.

How does a landscape built in a fraction of time represent time? How do you build a monument to a century, not an instance? Each bench, and the length of the curbing, is engraved with quotes spanning 125 years of the Penn community, both women and men, reflecting the mood of the era, the hopes and expectations for women, and the limitations and prejudices they met in their quest for higher learning. Holzer chose each quote from the Penn Archives, but they include more than a rose-colored celebration of feminism and victory. The quotes follow the timeline of the first women in degree programs, through the formation of the College for Women, then an integrated University, to the first female president of the University, ending at the turn of the 20th century.

“Holzer was strategic in the quotes she selected,” explains Lynn Marsden-Atlass, the curator of the University of Pennsylvania Art Collection since 2010. “The language is realistic and thoughtful, reflecting women’s time at Penn. Holzer did not sugarcoat their experience.”

The benches are made to be interactive, and the walkway is functional, historically running through the site that was once the College for Women, and a main pedestrian route. Marsden-Atlass worked with Holzer directly to resolve wear and tear on the benches over the years. In 2016, the benches were rusticated to preserve the quality of the granite and etchings.

We are absolutely opposed to co-education at the University of Pennsylvania. Note well that we do not say we are opposed to co-education in general, say we are opposed to the higher education of women. In many cases we are not even opposed to co-eds.

Editorial, The Pennsylvanian, 1921

Holzer broke conceptual artistic ground with her language-based art decades ago, largely with text-based LED light installations of phrases she had written, called Truisms. Much of Holzer’s language-based work, done in mediums like lighting installations, are experiential. Earlier this year, Holzer was commissioned to install another LED light installation, “For Philadelphia 2018,” at the Comcast Technology Center in Center City.

Claudia Gould, the former director of The Institute of Contemporary Art, chaired the committee that chose Holzer’s “125 Years” design from three applications. The committee also worked with Olin Partnership in Philadelphia as a consulting architect for the landscape elements, and lighting designer L’Observatoire of New York. Once Holzer’s design was finalized by the University Design Review Committee, Facilities and Real Estate Services (FRES) worked with a contractor to install the benches.

The committee wanted to commission an artist whose work would not only be renowned and valued in 50 years, but in 100 years and on. “125 Years,” with its language etched in granite, is a profoundly permanent work of art.

“Granite is expensive upfront, but it’s long-lasting, and has been used for centuries,” says Bob Lundgren, University landscape architect at FRES, who notes that Holzer was familiar with the material before her Penn installation.

The power and promise of a public art installation that is functional at its core (a pedestrian walkway, lighting, benches) has the potential to prompt a viewer to question the social and political landscape. Text that is entirely motivational and positive would do a disservice to the struggles and discrimination women faced throughout the century at Penn. It would also paint a false narrative of the actual history, making the piece more mythical than historical. Etching the words in granite of more than a century of women’s experience at Penn gives a weight and gravity to a legacy hard-earned—and solidifies the resistance women met along the way.

“This sculpture is an augmented element within the landscape,” Lundgren continues. “The Penn landscape is a contiguous and continuous palette of granite and brick. The buildings are all different, from modern to Victorian architecture, but landscape materials really unify the campus.”

The new traditions that are growing up around us have all felt your touch. The new regime for women will know your work and your ways.

Mary Monroe Search, 1927

nocred

nocred

Despite the commonality of water and ice, says Penn physicist Robert Carpick, their physical properties are remarkably unique.

(Image: mustafahacalaki via Getty Images)

Organizations like Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships foster collaborations between Penn and public schools in the West Philadelphia community.

nocred