Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

On March 16, a little more than a week after the first confirmed COVID-19 case in Peru was reported, the country ordered its borders closed. Kathryn (Kate) Hacker was following the news from the lab in Arequipa, Peru—3,593 miles away from Penn and the safety of home.

Thirteen days later, after the intervention of Penn’s Global Incident Management Team (GIMT) with an evacuation plan in place, and unexpected delays and complications overcome, Hacker boarded an embassy bus headed for Lima. Following a long bus ride, a chartered embassy plane from Lima to Dulles, an overnight in a hotel, finally, tired and grateful, Hacker was headed home via rental car to Philadelphia.

Hacker is one of hundreds of Penn students, faculty, and staff, who for one reason or another found themselves stranded due to travel restrictions, closed borders, and canceled flights, in the path of COVID-19’s spread. As the numbers of cases increased globally, the World Health Organization then declared a pandemic, further narrowing travel options and escape routes.

A postdoc in the Department of Biostatistics, Epidemiology, and Informatics at the Perelman School of Medicine, Hacker arrived in Arequipa in January to continue research on public health strategies for an insect-born vector that afflicts the region and causes Chagas disease. When Hacker realized she was in trouble, she reached out to her academic advisor Michael Levy, and he reached out to Penn Global. The request landed on Jaime Molyneux’ desk. Molyneux is Penn’s director of international risk management, the University’s point person for taking the call when a Penn traveler at risk needs assistance.

“The experience was stressful,” says Hacker. “Being able to make contact with Penn and talk with Jaime and interact with international security services was helpful. They were constantly texting me and giving me updates.”

Penn GIMT has been working nonstop for the last several weeks to evacuate and repatriate Penn travelers from far and wide. While Penn was able to help most of the stranded travelers with vital information and get them to limited seats on commercial flights, a few Penn travelers, like Hacker, had situations that were more complex. That is when Molyneux gets to work.

“When this broke,” says Molyneux, “we had a count of approximately 500 people abroad. Most were semester study abroad students. We are down to 20 maybe 25. We have three faculty still in Italy who have said they are going to stay and ride it out, and about 20 Penn study abroad students who felt it was safer to stay in place. Luckily, the University began to restrict and cancel travel beginning as early as January 24, otherwise we would have had an even larger task at hand.”

“Under normal circumstances, Penn has research ongoing and travelers in over 170 countries, territories and regions around the globe,” says Amy Gadsden, associate vice provost for global initiatives. “Supporting this work is core to achieving our goal to bring the world to Penn and Penn to the world. During a crisis, we are prepared to pursue every avenue to assist our students, faculty and staff overseas and we are fortunate to have leaders at Penn that are committed to ensuring we can do that.”

On a typical day, Molyneux’s job might include working to facilitate a medical response for a Penn researcher who trips and falls or breaks a limb and needs to go to the hospital, or to help arrange outpatient appointments that need to be set up while a student is studying abroad. It can also include advising on high-risk travel for a faculty researcher who has a grant to protect cultural heritage sites in Iraq. But the last couple of weeks have been anything but typical.

“My job is responsible for the health and safety of Penn travelers abroad: students, faculty, and staff. We urge all Penn travelers to register their travel so we can provide that support. The majority of my work should be pre-departure training, and risk assessment—that is 80% of my day,” says Molyneux.

“I am also on emergency response, on call 24 /7. Any incident that comes in through International SOS (ISOS), or Penn Police, comes to me to decide what our response will be. As far as these security evacuations or natural disaster evacuations they don’t happen often. Perhaps once a year—by example, the earthquake in Nepal or flooding in Tajikistan—it is not usually this large scale. We have not had such a large-scale evacuation need since the earthquake in Japan in 2011, but even that was just one country.

“This situation where the entire world is impacted including our country—to see the CDC go to its highest level of risk and the U.S. State Department take the whole world up to a level 4—it’s unbelievable,” Molyneux says. “To have everybody around the world needing to come home at the same time, is hopefully a once in a lifetime thing.”

Penn partners with different service providers to support these efforts using ISOS for travel assistance, for evacuation negotiations, and security advice. Behind them is a travel medical insurance partner, and travel agency partners who help with flights and travel assistance.

“If you are a United States citizen,” says Molyneux, “you typically would go to the U.S. Embassy, but many of our travelers are not U.S. citizens. So, we are often working with foreign embassies which makes it more complicated. We are still working to assist a Penn professor in Greece in this situation. And given the breadth of the situation, embassies have been stretched.”

Maintaining relationships in the Department of State and embassies across the world is key to her work says Molyneux. Penn is a higher education member of a corporate branch of the Department of State sharing intelligence. Penn is also a member of Pulse: Higher Education International Health and Safety Professionals, which is a collaborative network of health, safety, and security professionals whose positions are primarily dedicated to higher education international travel, activities, and operations.

Molyneux says, “In this instance, in Peru, we had a Penn Global staff person reach out to say that he knew somebody in the U.S. Embassy in Peru and do you want to talk to him? And it happened to be the person who was working on getting my student out.

“Beyond the contacts we already have, it is great to be able to reach out to Penn faculty, staff, and Ivy peers to find someone that knows someone, that is how we are often able to facilitate personalized help.”

Even with the contacts and hard work being done on Hacker’s behalf, her evacuation plan changed three times as options opened and closed—with Molyneux and ISOS working closely with embassy officials and others to guide her to safety.

“Jaime first tried to get me a flight from Arequipa to Cusco, and then a flight back to Miami,” says Hacker. “Those flights were denied by the Peruvian government—it was confusing because the rules kept changing daily about what was and was not allowed. So, then the plan became to drive me to Cusco, a nine-hour drive and fly me out on one of the chartered U.S. embassy flights. But then the rules changed again and the move between the two municipalities became impossible.

“ISOS then put me in touch with a group that was organizing a bus to get twenty students doing a foreign exchange from Brown University out of Arequipa to Lima. They had worked with the bus company and local police to gain permissions to drive.”

Before any bus could operate, however, passengers had to have proof that they were on the manifest for an embassy flight out of Lima. Waiting to get these flights confirmed, the first bus was delayed for several days. Phone calls and text messages passed urgently between Molyneux, ISOS, and Hacker.

“They wanted to be sure we had been cleared for flights before we left from Arequipa,” says Hacker. “Finally, the embassy decided to charter and operate a bus to transport about 100 Americans from Arequipa to Lima. We were all told to get to the central plaza by 2 p.m. for health checks to be processed for a 4:30 p.m. departure. The effort to get to the meeting place, was hard. Due to the quarantine, only authorized vehicles could be on the streets.”

After 40 minutes a taxi with approval was secured driving Hacker to the designated spot.

“It was overcast but warm and bright sun occasionally punctuated through the clouds,” says Hacker. “The scene was strange. The Plaza de Armas in the center of the city is striking. It is built of beautiful white volcanic stone and has a big cathedral. Americans drifted in from all sides, many with families, some walking several miles, some also managed taxis. The promised health inspections never happened. So, we spent several hours in the plaza standing around trying to figure out what to do. There was a guy who was selling N95 masks and military police with large guns.”

After a two-and-a-half hour wait, Hacker boarded one of five buses. People on the bus were anxious but in good spirits, says Hacker. “Everyone was sharing what food we had, hand sanitizer to wipe down seats etc. We knew it was going to be a long bus ride.”

The 15-hour drive to Lima stretched to 17-hours with the multiple police checkpoints set up as part of the quarantine. When they arrived at the embassy early the next morning, Hacker says a line of U.S. citizens trying to get out of Lima had already formed.

“The embassy was taken as much by surprise by these evacuations as we were,” says Hacker. “So, they had set up a camp outside the embassy grounds with porta potties and they were checking our passports. Then they put us back on another bus where we waited for another hour before being driven to an airport hangar at the military airport in Lima. There they checked our bags and passport security came through before we boarded yet another bus to the plane.

“We arrived in Dulles around 1 a.m. and I had initially planned to just rent a car and drive to Philly that night—train travel was an option but as an epidemiologist my gut was you don’t hurt anybody with an abundance of caution, so I rented a car to limit my contact with other people. In the end, I was way too tired so slept at a hotel and drove home the next day.”

Hacker commends the embassy and the U.S. repatriation effort. She says, “When I felt anxious, Jaime and the team provided me with a sense that something was happening, and they were trying to get me out. Knowing that people at Penn and the embassy were fighting for me to get home was a real comfort.”

All the while working on Hacker’s evacuation, Molyneux and the team were also helping three students out of Morocco, and another out of Senegal in addition to fielding calls aiding those who had opted to stay in place abroad.

To facilitate the Morocco evacuation, Molyneux identified one of the three students, first year Wharton MBA Valerie Chia, as the leader and point of contact for the group. By the time that country shut down all incoming and outgoing international travel, Chia described a situation bordering on panic as the then group of 10 students she was traveling with scrambled to rebook flights and find seats on the few flights still getting out.

“Many of us were on the phone until 3-4 a.m. with various airlines trying to get more information with limited success,” says Chia. “When some of us failed to secure flights, we reached out to the U.S. Consulate in Casablanca. Someone from our group spoke with a representative there who said they were working on repatriation flights and that we should register for STEP [Smart Traveler Enrollment Program] and stay tuned for more details.”

But waiting became troublesome. Chia says that while their hosts in Fes were warm and supportive, there was a general growing animosity towards foreigners. “As things on the ground started to escalate and become more restrictive, the three of us traveled to Casablanca with the expectation of staying there until we were able to get on a repatriation flight out.”

Back at Penn anxious classmates reached out to Eddie Banks-Crosson, director of student life in the Wharton School, who contacted Penn Global and the Department of Risk Management.

“After that we were connected to Jaime,” says Chia. “We are so incredibly lucky and grateful to be part of the community at Penn. Even before we were desperate to get home, we had so many classmates and friends reaching out asking how they could help.

“It was so reassuring to know we had people back home who cared about us and were advocating for us and our safe and speedy travels home.”

Molyneux reached out to ISOS to seek some options on how to get the three students out of Morocco.

“They were all U.S. citizens, needing to get back to the U.S.,” says Molyneux. “ISOS were able to get an 8-seater plane out of Casablanca to the U.K. within just a couple days. So, we booked the plane not knowing if the other five seats would be filled. I reached out to Ivy League colleagues to ask if anybody else need seats out of Morocco. And soon all the seats were taken. We got the students to London and helped them to arrange their flights back to the U.S.

Once safe, Chia sent Jaime a photo and email to thank her.

“They were very happy and sent me a picture—it was the best picture I’d ever seen,” Molyneux says. “Because I never get to see people that I help, sometimes I never meet them. I talk to them non-stop, and I talk to family members, but to actually get to see her smiling and with such a sign of relief on her face. It was really nice to get that picture.”

Molyneux, however, had little time to celebrate the success. Her mind was still on getting Hacker out of Peru and Bina Brody and her family out of Senegal. “Until we know everyone is safe, we are here,” she says.

Brody, a fourth-year doctoral student in linguistic anthropology, her husband, and their two young sons ages 4 and 1 1/2, were stuck in Dakar where she was conducting field work on a traditional Senegalese wrestling ritual. Her work was to have taken 10 months. The family had given up the lease to the house they had in Princeton and expected to be in Senegal through the end of August.

Thanks to the efforts of Penn’s Global Incident Management Team they have been back in the U.S. for five days, living temporarily in a family friends’ home in Connecticut.

Brody, who works with advisors Timothy Rommen and Asif Agha says, “Leaving Senegal was a tough decision with two little kids. But it is definitely a relief. We would be happy to be in Senegal if we could, but it is a big relief to be settled for a while and be safe.”

Brody’s evacuation was also arranged through embassy connections.

“Our decision to leave was complicated because of the children,” says Brody. "Making any move or decision to leave abruptly is a challenge with children, but at the same time, we wanted to make sure not to put them in any extra risk if we could avoid it. For the moment, being in the USA and close to family feels like the best decision.

"One of my fellow colleagues had a similar situation and they recommended talking with Penn Global. I first got in touch with Artemis Velahos Koch, executive director of global support services, to ask what our options were. They were really helpful and calm which was nice and looked into various solutions, chartering a plane, embassy flights etc. We immediately registered for an embassy flight but didn't receive confirmation that we would be on it. When we started to get nervous, Penn global stepped in. They really pushed for us to be on the flight, and got members of Congress to intervene on our behalf.

“Dakar has been wonderful to us. The people are so friendly and warm. There you feel it [social distancing] more because they are so welcoming and closer physically and emotionally than you see in other places. In the COVID-19 outbreak they discovered two or three cases that were brought in from abroad and the president shut down all flights and inter regional travel. Travel was forbidden and schools were closed. There it felt unnatural not to be able to hug with an embrace or offer a handshake. The streets had become strange and quiet.

“Our first flight was postponed by a day, so we were grateful when the evacuation plane finally took off. It was a surreal experience. It was a cargo airplane with almost no windows—just a huge empty space fitted with seats. It was set up to be a medical evacuation plane and the crew were all in full hazmat suits.

“The plane held about 150 seats and was full. Two fully equipped ER rooms were taped off at one end. There was a space at the back set up for quarantine. When we boarded, they took everyone’s temperature and fortunately no one needed to be quarantined. There were some snacks and food and a lot of people were wearing masks, which was unnerving for little kids. It was organized and everyone was in good humor, but there was no estimated time of arrival it was unsettling.”

Brody says, “We are so fortunate, so grateful. ISOS and Jaime have been phenomenal and went above and beyond in thinking about how to help my family. Obviously, everyone is feeling this deep sense of uncertainty at this time. To be able in these last few days to go out into nature and exercise with the kids and know we are safe here and everything is fine, has been a blessing.”

Reflecting on the recent evacuations, Molyneux says, “I was on the phone with our evacuation provider and I said have you ever been in a situation where every single country is impacted. Usually you are focusing on one region, on one country. But this is unbelievable for everyone and very scary. I have been working in this position for eight years and I’ve never seen anything like it.

“We are glad we could help Kate, Valerie, Bina, and the others get home safely. Many people do not know the importance of registering their travel with Penn. There are so many resources available for them. But,” she adds, “hopefully we will never see anything like this again in our lifetime.”

Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

nocred

nocred

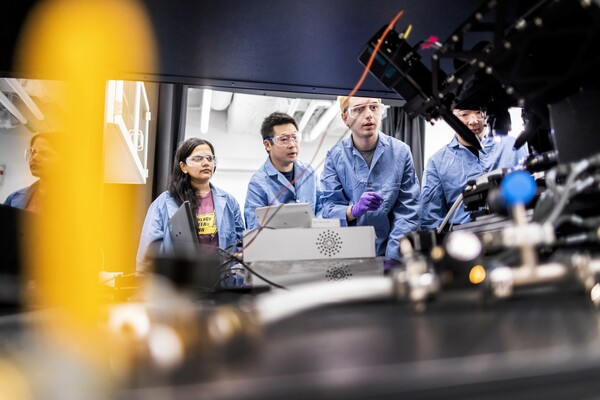

(From left) Kevin B. Mahoney, chief executive officer of the University of Pennsylvania Health System; Penn President J. Larry Jameson; Jonathan A. Epstein, dean of the Perelman School of Medicine (PSOM); and E. Michael Ostap, senior vice dean and chief scientific officer at PSOM, at the ribbon cutting at 3600 Civic Center Boulevard.

nocred