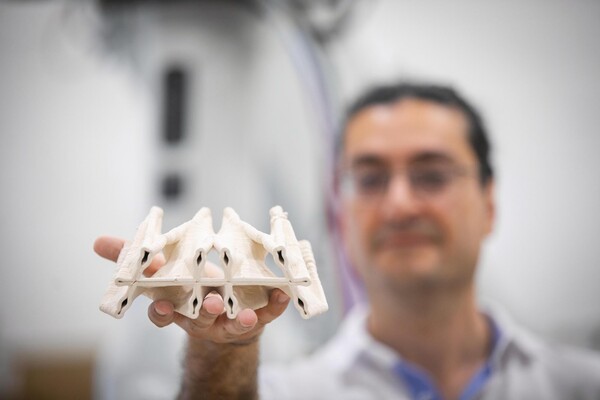

The Polyhedral Structures Laboratory is housed at the Pennovation Center and brings together designers, engineers, and computer scientists to reimagine the built world. Using graphic statics, a method where forces are mapped as lines, they design forms that balance compression and tension. These result in structures that use far fewer materials while remaining strong and efficient.

(Image: Eric Sucar)

In the top image, Jews carry wheat in the Emek (Jezreel Valley) of British Mandate Palestine in 1936. The bottom photo shows the 1868 restoration of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

In the top image, Jews carry wheat in the Emek (Jezreel Valley) of British Mandate Palestine in 1936. The bottom photo shows the 1868 restoration of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.