(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

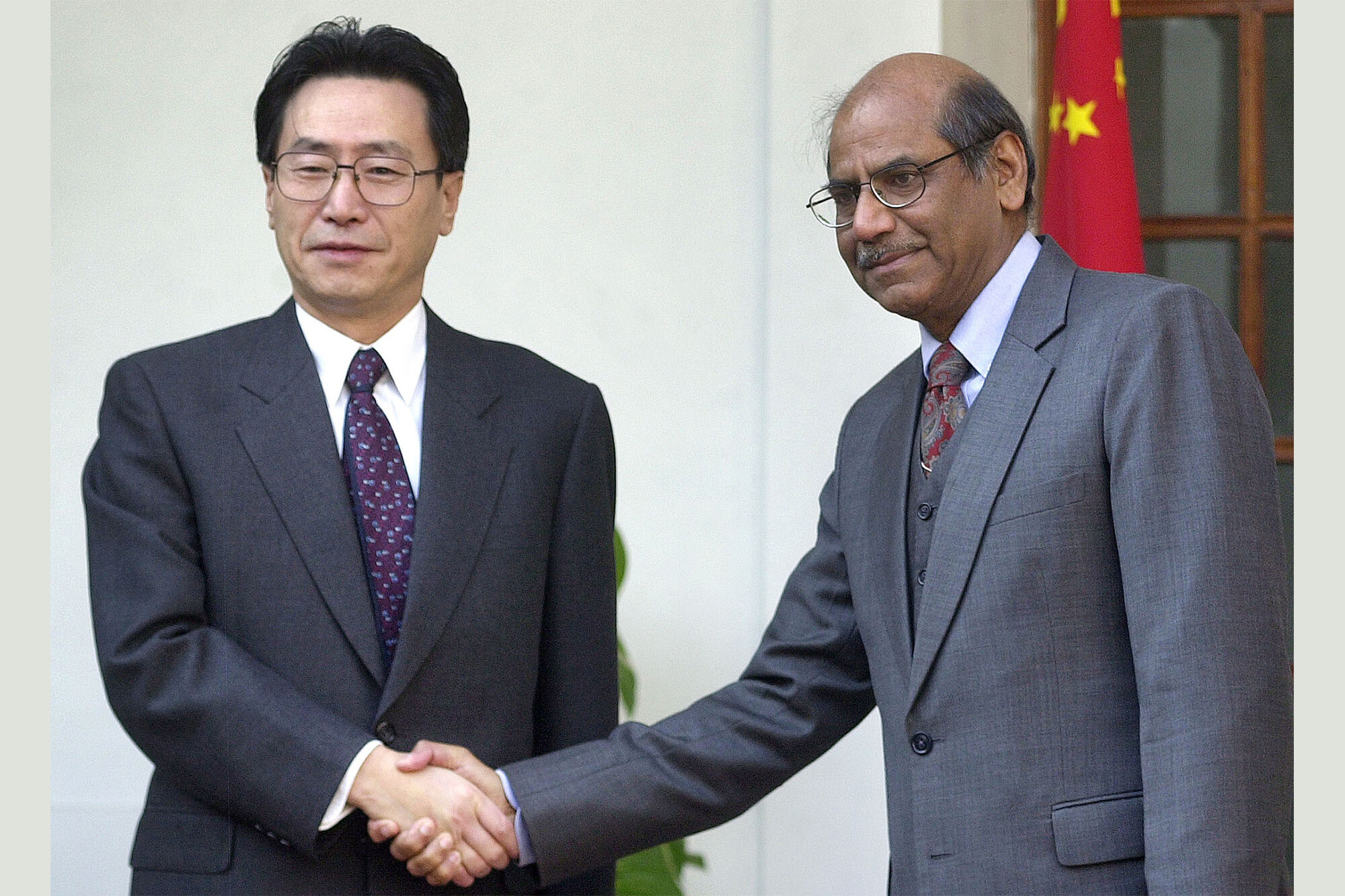

On Feb. 24, former Foreign Secretary of India Shyam Saran spoke via Zoom to deliver the Nand and Jeet Khemka Distinguished Lecture, themed around overlapping peripheries and how India and China will navigate what Saran’s referred to as the “Asian Century.”

The lecture was presented by the Center for the Advanced Study of India (CASI). It’s part of a broader effort to stimulate thinking about the relations between India and China, says CASI Director Tariq Thachil, an associate professor of political science in the School of Arts & Sciences.

“The importance of understanding this relationship cannot be overstated: India and China account for 35% of the world’s population, are two of the world’s five largest economies, and share a border longer than that between the U.S. and Mexico, a border along which relations are both complex and contentious,” says Thachil. “In thinking of whom we would like to hear from regarding dynamics between these two Asian giants, we immediately thought of Ambassador Shyam Saran.”

Saran worked in the Indian Foreign Service for 30 years and served as foreign secretary of India from 2004 to 2006. He also served as a special envoy for Indo-U.S. nuclear issues and as a chief negotiator on climate change.

After brief introductions by Thachil, Saran opened by acknowledging the tragic events unfolding in Ukraine and cautioning against a too-narrow view of the invasion.

“I think that, in looking at what is happening in Europe, we have perhaps lost some focus on the role that China has played and will play in this unfolding of events,” Saran said, citing a Feb. 4 joint statement between China and Russia that he considers a landmark document that may signal a geopolitical shift.

Of interest to the ambassador in the statement was this line: “Russia and China stand against attempts by external forces to undermine security and stability in their common adjacent regions …” with Saran emphasizing the final three words as indicative of Chinese and Russian security interests extending beyond their current borders.

He also warned that China may assess the current international response to the invasion of Ukraine as a “rehearsal” for what might happen should it decide to invade Taiwan. In this sense, he clarified, China has been an “enabling element” in what has unfolded.

Regarding the current relationship between India and China, Saran said that because China has a hierarchical view of its role in Asia, its relationship with India has grown increasingly tense. China, he said, considers itself a historically long-standing power in the region that is only reclaiming a leadership role it previously maintained for centuries.

“Harmony can only be maintained if there is a respect for hierarchy,” Saran said of the Chinese view. “That is, every entity should know where it belongs in the pecking order, in a sense. … And as far as China is concerned, it should be at the top of the hierarchy.”

There’s also a sense among China and Russia, Saran said, that the opportunity to act is now—an opportunity that may not come again.

“If you look at Chinese writings, there’s increasingly a view that there is a moment of opportunity for China, and I think this is the same as far as Russia is concerned,” he said. “That there’s an opening in the international system as a result of the relative weakness of the United States—perhaps a domestic political polarization in the United States that makes it difficult to have decisive leadership, and a sense that power may be there, but that the willingness to use that power has diminished.”

For India, this has all occurred in the backdrop of a country that’s become closer with Russia, in terms of managing what Saran calls a “near neighborhood” relationship, but this may become complicated as Russia seemingly grows closer with China. A concern, he said, is that Russia may now bend to China on matters unfavorable to India.

Further complicating India’s relationship with China is that the two remain in ongoing disputes over their shared border. Conflict turned deadly in June 2020, the first time this has happened since the 1970s.

“The difference this time has been that in responding to or projecting the clash … the Chinese did not say there was a difference in terms of where we thought the Line of Control was, but instead [said], ‘This is sovereign Chinese territory,’” said Saran. “As soon as you say [that], where is the room for compromise?”

All of this is to say, he concludes, that India stands in the way of China’s view of a hierarchical pecking order in the region. Significantly, India also did not support China’s Belt and Road infrastructure initiative. But it faces an uphill battle in establishing a strong position in international relations as China continues to accelerate well beyond India’s rate of economic development.

“India is faced with a situation where there is a diminishing asymmetry between China and the United States, but there is an expanding asymmetry between China and India. So, it’s a kind of double challenge for India,” Saran said in closing, adding that existing assumptions about these relationships need to be rethought. “That’s very important for the future of Asia.”

More CASI events on Sino-Indian relations will be hosted in the weeks ahead, such as a moderated conversation with authors Joy Ma and Dilip D’Souza, and a talk from CASI visiting scholar and Penn alumnus Swagato Ganguly.

(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

Jin Liu, Penn’s newest economics faculty member, specializes in international trade.

nocred

nocred

nocred