nocred

3 min. read

Large data sets can just look like rows and columns of numbers to the average person. But to those who know the tricks of the trade data can reveal startling moments of enlightenment about the underlying institutions, challenges, or situations that created it.

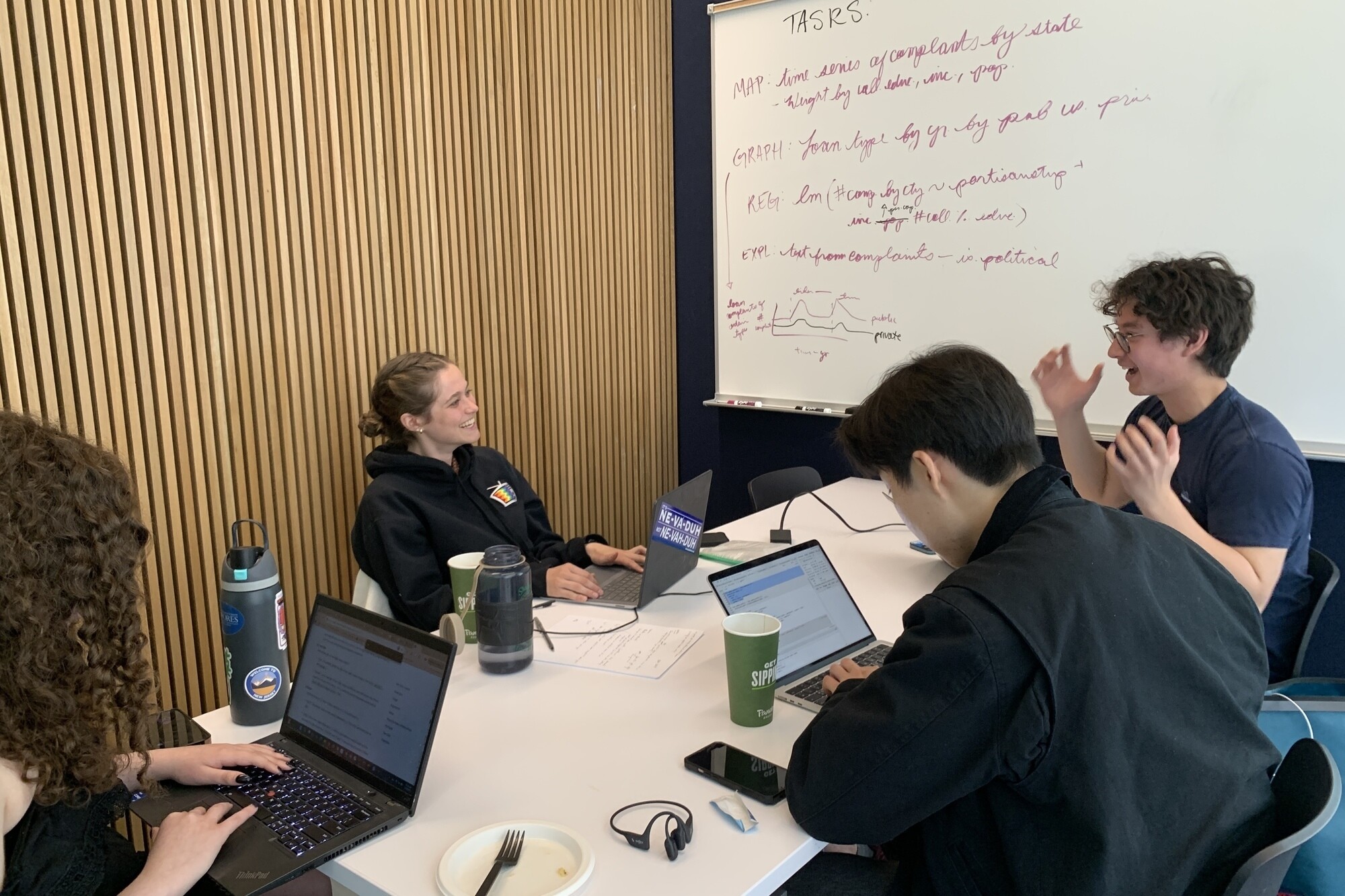

That was the case for nearly 20 students in the recent “hackathon” organized by the Penn Program on Opinion Research and Election Studies (PORES), who put their data science skills to the test sorting through huge volumes of information in search of lessons.

Equipped with laptops, statistical software, mapping programs, algorithms, and visualization tools, students were given a short deadline, handed the data at 10 a.m., and told to present their findings at 4 p.m., said hackathon coordinator Andrew Arenge, PORES director of operations in the School of Arts & Sciences.

Their assignment was intentionally loosely defined: “Find something interesting.”

“What we’re trying to do is give them a real-world experience,” Arenge said. “It’s always exciting when they land at different places” and find new information or apply unusual tools.

Now in its sixth year, the PORES competition began during the pandemic to engage students and keep them interested in data science, even over Zoom. “Everybody was at home and had tons of time,” Arenge said.

Despite the event’s name, there was no hacking involved, just digging and data crunching, Arenge said. Teams were provided with large sets of consumer complaints from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), and they could use other data in their analysis, such as from the Census Bureau or voting information.

Five teams vied for honors for best question, creativity, visualizations, presentation, and findings. The judges were Damon Roberts, manager of elections at ABC News; Scott Bland, senior politics editor at NBC News; and Patrick Tucker, senior research statistician at Edison Research. Penn political science faculty and PORES staff also attended the final presentations.

The team of College of Arts and Sciences fourth-years Justine Orgel, Diya Amlani, Arushi Saxena, and Cecilia Duncan studied political partisanship and media consumption as measured by FCC complaint data and won the Best Visualizations honor. They found that, for example, Republicans were more likely to file complaints about indecency, but they were significantly less likely to complain about net neutrality.

The team of College second-year Colin Cham, Wharton School third-year Seher Taneja, and Fels Institute of Government graduate student Samantha Lopez-Rico explored do-not-call lists and about 1.6 million nuisance-call complaints. They reported that in their study of California complaints, higher-income areas had about five times more complaints than did poorer ones, receiving the Best Question Raised award.

Wharton first-year students Sebastian DeLorenzo, Sonya Colattur, Dev Karpe, and Dhruti Shah looked at both FCC and CFPB complaints to learn how the agencies could optimize their resources to respond to the highest-priority complaints. They created a model to sort through the text of complaints beyond standard keyword searches, receiving the Most Creative Approach honor.

Exploring whether New York City or Philadelphia’s population was grumpier, College second-year students Lucas Zhu, Andrew Lu, and Asha Chawla and fourth-year Seamus O’Brien used CFPB data to examine the types and intensity of complaints. They concluded that while Philadelphia had more complaints than New York, the latter was more successful with getting monetary relief, taking home the Best Presentation award.

And the team of College third-years Glynn Boltman, Ki Joon Lee, Geddy Lucier, and Jackie Balanovsky examined the factors affecting complaints about student loans, including presidential terms, lenders, and geographic locations, and received the Most Interesting Finding accolade. They found in part that for every single unit of increase in Republican support there were eight fewer student-loan complaints.

As some projects show each year, Arenge said, not every day of work results in a neatly packaged conclusion. Sometimes initial hunches are not borne out by the data—a trend that occurs in the real world as well—and students can end up going down rabbit holes. “The goal is to push their skills and thinking,” he said.

nocred

nocred

Despite the commonality of water and ice, says Penn physicist Robert Carpick, their physical properties are remarkably unique.

(Image: mustafahacalaki via Getty Images)

Organizations like Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships foster collaborations between Penn and public schools in the West Philadelphia community.

nocred