Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

This story originally appeared in the Oct. 26, 2017 edition of the Penn Current Express.

The Vietnam War ended in 1975 after 20 years of fighting and more than 55,000 Americans and between 3 and 4 million Vietnamese dead.

North Vietnamese tactics, management, and resilience were able to overcome the super-powerful tools and instruments of war of the United States, which was weakened by ineffectual leaders, poor policy and planning, and social unrest at home. The war split the country along partisan and ideological lines, a divide that still remains.

Americans of a certain age do not like to think about the long, lost war, and the reasons for the country’s defeat. The War in Vietnam remains tucked, generally, in the deepest recesses of the national consciousness, reemerging now and then like a repressed memory, brought back for cultural or historical reasons, like Ken Burns’ recent 10-part, 18-hour documentary “The Vietnam War.”

“I think we Americans are very deeply troubled by it because it exposed defects in our character, and also defects in our competence,” says Arthur Waldron, the Lauder Professor of International Relations in the Department of History in the School of Arts & Sciences. “We like to think of ourselves as always being good, and I think that in the abstract, we were on the right side, which was to stop communism. But the way that we did this was so totally incompetent that it led to just a ghastly tragedy.

“It’s quite understandable that we sort of pretend that this never happened, but it was tremendously formative,” Waldron adds. “The country that we live in today is post-Vietnam America.”

An Asia expert who was previously a professor at the U.S. Naval War College, Waldron teaches the seminar “The Vietnam War: Issues and Interpretations” and the lecture course “The Vietnam Wars: 1945-1979.” On account of new knowledge and research from a diverse group of scholars, such as the book “Hanoi’s War: An International History of the War for Peace in Vietnam” by Penn alumna Lien-Hang T. Nguyen, Waldron says the general understanding of the war in the United States is changing.

“In 1975, everybody in America thought the same thing—and most of them haven’t looked at it since, so they still think the same thing,” he says. “But, in fact, there have been some people studying the war, so now the whole picture has changed. As a result, the whole story is going to change, and it’s being changed by facts, not by opinions.”

Penn Today sat down with Waldron at Perry World House to discuss undergraduate students’ knowledge of the Vietnam War, mistakes made by the U.S. leadership, the failures of President John F. Kennedy, and the effects of the war on the Vietnam generation.

I had a very unusual set of experiences before the Vietnam War, which enabled me to put it in an international context. When I was a teenager, I had gone to school in Europe for a year as part of an exchange program. I discovered that there was a teacher who organized groups to go to the Soviet Union, so I signed up. Starting in my senior year of high school, I traveled to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union. This was at a time when they still felt confident and we still thought they were going to overtake us economically. I traveled all over Eastern Europe and communist countries, and that basically persuaded me that the information about communism coming from America was not propaganda, but, in fact, a place like East Germany really was a lousy place to live. A lot of people came to the Vietnam War knowing only America, so if you said, ‘There are communists fighting in Vietnam,’ they didn’t really know what communism was. But I had been exposed to it very thoroughly. It’s sort of like being vaccinated. So when someone told me about how great Ho Chi Minh was and how he was going to make Vietnam into a paradise for the Vietnamese people, I said, ‘I heard that before.’

Very little. But remember how long ago it was. It ended in 1975. That’s more than 40 years ago. One of the things that I’ve discovered is that students who were born such that they’re 18 now, they don’t have any sense of the war. It’s ancient history. For me, it would be the equivalent of a war happening in 1910, so I spend a lot of time trying to set up particularly a sense of what America was like before we completely messed up and humiliated ourselves in Vietnam.

As far as I can tell, we had no good intelligence about the enemy, or even about Vietnam itself. There was no sense of urgency that before we did anything, we should really find out a lot about the country and about the combatants. We should know the names of all the North Vietnamese leaders, and have some idea of what their political views are, what kinds of internal fights they were having. Also, the failure to understand strategy transformed the nature of the war. Had the strategy been properly understood and conceived, it’s quite likely that the war could have been ended successfully in a matter of years at most. But the strategy was misconceived and we created a sink into which you could pour as many American troops as you wanted without making any difference because you weren’t hitting the enemy where it hurt.

I would probably blame Kennedy above all, not so much for what he did, but for what he didn’t do, which was to listen carefully and think it through, really work on it like homework.

If you read his inaugural address, it’s a great speech, it’s a wonderful piece of English, but it overpromises, and it reflects what I would call American arrogance—if not even hubris—the sense that we can fix everything, we can do anything. It portrays us as being more powerful and better than we really are. It makes us almost take on a mission of sort of saving the world. It conveys a degree of pride and confidence that is way out of line, that only a god could have, and so, therefore, it raised the expectations of the American people to a level which could not possibly be satisfied.

In the Vietnam War, really the worst influence on our strategy was Averell Harriman [assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs]. He was ambassador to Russia in the [Franklin] Roosevelt administration, he was at the Yalta talks, he was governor of New York. Harriman was the one who messed up the Kennedy policy. Harriman is the person who promoted the neutralization of Laos, and he’s also the person who advocated for the murder of the President of South Vietnam Ngo Dinh Diem. Harriman just hated Diem, and he worked around Dean Rusk, who was our secretary of state, to prevent Rusk from controlling policy. And as a result, Kennedy got conflicting advice, and Harriman in the end was able to arrange for the killing of Diem. The problem with that is, who takes over after Diem? Well, it is the military and generals. In this country, we’ve had many presidents who are famous for their military service, but in Asia, that’s not the way it is. In most Asian countries—this was true in the old days, it’s less true now—the army is the tool of a particular political group, so the people tend to look down on them. It was very hard for the generals to lead the state. By the end of the Kennedy administration and the assassination of Diem, it’s like a chess game where you make such disastrous moves that there’s almost no way you can win the game unless you start over. We did such stupid things that before the war was really being even fought, our strategy was so flawed that it made defeat very easy.

There was a shift in policy between Eisenhower and Kennedy. Eisenhower understood the strategy of the situation. He told Kennedy, the day before Kennedy was inaugurated, that he could go into Southeast Asia or not. It’s a choice. You don’t have to. If Vietnam goes, it’s not the end of the world for the United States, but if you do go in, Laos is the country that is the key. If the communists were able to go into Laos and just start coming into Vietnam from the west, down a thousand miles of border, there’s no way you could hold Vietnam. Eisenhower stressed that, but the Kennedy administration reversed everything that Ike had figured out. Kennedy was very foolish not to spend more time listening to Eisenhower.

There was a very strong element of social prejudice, and there was a kind of clubbiness about the Kennedy administration, a social clubbiness that made someone like Eisenhower unwelcome. Eisenhower was born in Kansas. He went to West Point. He never went to Harvard. He never lived in the Northeast. The Bostonian Kennedy crowd looked down on Eisenhower because he was a West Point grad, because he came from Kansas, because he was not socially prominent.

By 1959, there had been a big party fight in Vietnam, and a man named Le Duan basically became the strongman. He was the one who was calling the shots, and Ho Chi Minh, whom everybody had heard of, was sort of sidelined. Le Duan decided they were going to invade South Vietnam because he had been down there, and he saw that the South Vietnamese were not crazy about their government. They respected it, but they didn’t like it. The South Vietnamese wanted a more democratic government, and a freer government, and they didn’t want communism at all. Le Duan and his people said the only way to invade South Vietnam is to send our soldiers because there aren’t enough South Vietnamese who are communists to put together even a little army. So by 1960, they had already decided to invade, and that they were going to build a passage through Laos called the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In 1960, there was already a kind of prototype of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. It got much bigger, but it was already there in 1960. So even before Kennedy made his decisions, the North Vietnamese had already shown their hand. If we would have had good intel, we would have asked, ‘Why have they built this road leading from Vietnam all the way down to the sea?’

Johnson had the opportunity to remedy the mistakes, but Johnson was a very self-centered man. He could have said, ‘Look, we’ve got problems, let’s get our top 20 strategists together and figure out what we’re doing, and we’ll do it right this time.’ He didn’t do that. He just said whatever Jack Kennedy would have done is fine with me, and he just kept sending American high school students and college students by the hundreds of thousands.

I think everybody who went through it was affected. Everybody who was an undergraduate or was around 18 or 20. The only comparable group I can think of are the people who are about five years or so older than me who were in the Civil Rights Movement. I know people who went to the South in the days of real, old-fashioned segregation, and the imprint of the experience on their characters was very, very deep, and it really formed the rest of their lives.

It was extremely educational, and it strengthened in me the belief that I had to get out of the American bubble, because America is big enough that you can think it’s the world, but it’s not, it’s very different than the world. I had to get out of this American bubble, I had to go somewhere that is completely different, I had to do something that’s worthwhile, but is hard work, and I had to let my brain kind of come to equilibrium because at that time I couldn’t figure out which way is up. So I went out and I studied in Taiwan, and learned Chinese. Basically, that’s the beginning of the story of how I ended up here. That was partly a reaction to the Vietnam War because the Vietnam War, among other things, was a display of American ignorance about foreign countries.

Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

nocred

nocred

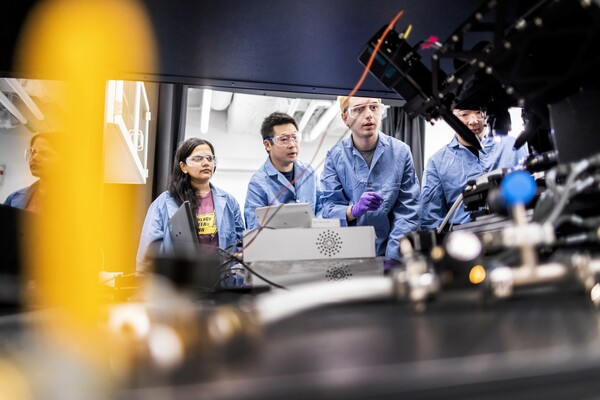

(From left) Kevin B. Mahoney, chief executive officer of the University of Pennsylvania Health System; Penn President J. Larry Jameson; Jonathan A. Epstein, dean of the Perelman School of Medicine (PSOM); and E. Michael Ostap, senior vice dean and chief scientific officer at PSOM, at the ribbon cutting at 3600 Civic Center Boulevard.

nocred