(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

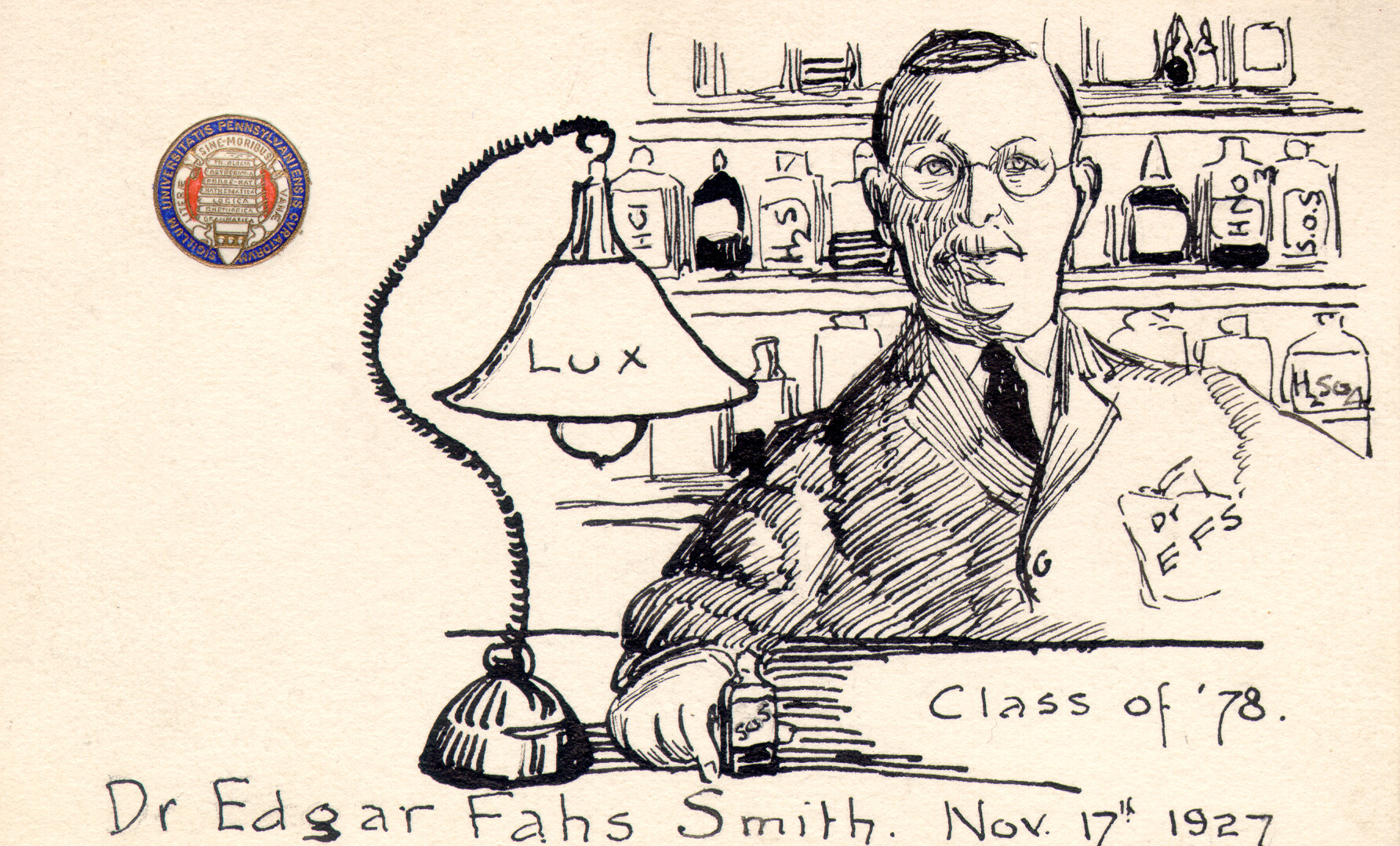

On the northwest corner of the Vagelos Laboratories just off 34th Street, a bronze statue gazes down at pedestrians as they make their way onto the tree-lined path that connects the chemistry and engineering buildings to Shoemaker Green. The devilish figure under Smith’s left shoe is meant to represent “error,” which Smith is stamping out through science.

The likeness of Edgar Fahs Smith, a distinguished professor, researcher, administrator, and historian, stands as a physical testament to his legacy, one that is embodied not only by his academic achievements and service to the University but also by the historic collection that he left behind for future generations of chemistry historians and students.

Smith was born in Pennsylvania’s West Manchester Township, just outside of York, in 1854. Growing up under the shadow of the Civil War, Smith and his younger brother lived in the central part of the state with their Scotch-Irish father and German mother.

Smith attended York County Academy, now York College of Pennsylvania, where he studied classics in preparation for college. He was also a devoted student of science and history and found himself “beckoned” by the fields of chemistry and medicine.

While Smith was majoring in chemistry and mineralogy at Pennsylvania College, now Gettysburg College, his mentor noticed the young man’s strong aptitude for chemistry and encouraged him to continue his studies beyond college. After earning his bachelor of science degree in 1874, Smith travelled to Germany to study at the University of Göttingen.

Working with Friedrich Wöhler, a pioneer of the field of modern organic chemistry, Smith’s two years in Germany provided him with a new perspective on scientific research and the cultural value of university study. He returned to Pennsylvania in 1876 with a Ph.D. in hand and married Margie Alice Gruel, whom he had met while in college.

Smith began his academic career as an assistant professor in Penn’s Department of Chemistry, where he became known for his engaging teaching style. After two brief stints teaching at Muhlenberg College and Wittenberg College, he returned to Penn with the help of students and colleagues who petitioned to hire him when a position opened in the department.

Many of Smith’s research achievements were in electrochemistry, focused on reactions that produce or use electricity. While studying new ways to apply electrical current, he developed a new approach for electroanalysis that allowed metals to be more quickly separated from mixtures. This helped Smith isolate elements of “exceptional purity” and obtain more accurate atomic weights for 18 elements.

Smith was known for being an excellent instructor and author who wrote more than 250 academic papers. Smith and colleagues at other institutions played an instrumental role in changing the landscape and improving the quality of academia in America at the turn of the 20th century.

Beyond his academic and scientific achievements, Smith was well-known for his contributions to the history of chemistry. He began collecting items during his time in Germany and became even more serious later in life, amassing manuscripts, books, portraits, and equipment that attracted chemists and historians to Philadelphia from around the world.

“As a chemist and practicing researcher, Smith became interested in history because he realized that his students didn’t understand the history of chemistry and therefore they didn’t understand how the field developed,” says Lynne Farrington, curator of the Smith Memorial Collection, about the inspiration behind his extensive holdings.

Smith’s collection contains a number of practical books and manuscripts, including works on distillation, dyes, yeast, alchemy, gaslights, pharmacy, and even brewing, that describe the ways people used chemistry to transform the world.

Many of these historical resources are still being used today, from pharmacists looking for “new” medicines to conservators who want to restore paintings using materials that the original artist used. “Chemistry touches all aspects of our lives. For this reason, Smith was interested not simply in the theoretical realm but also in chemistry’s practical applications,” says Farrington.

Smith had a specific interest in the history of chemistry in America, and especially in Philadelphia, which was a center of science during colonial times. His 1914 book “Chemistry in America” is a testament to this passion, detailing the lives and works of numerous American chemists as well as the scientific societies that helped shape the field.

During the course of his 44 years at Penn, including his service as vice provost from 1899 to 1910 and from 1911 to 1920 as provost, a position that was the equivalent of the current-day president, Smith witnessed a period of growth that saw a doubling of the student body and the teaching staff. Smith was also dedicated to developing Penn’s undergraduate medical education program and expanding medical research at the University.

Outside of his scientific, academic, and administrative achievements, Smith was known for being a knowledgeable and effective instructor who supported his students. He taught many of the first female students at Penn and was an outspoken advocate for women in chemistry.

After his death in 1928, his wife took over the management of the collection to ensure that it was properly cared for and curated. Thanks to various dedicated endowments the collection continues to grow, adding to the thousands of books, manuscripts, pamphlets, photographs, engravings, and chemical apparatus. Whether it’s being used for teaching freshmen seminars on the history of chemistry or used by researchers interested in the history of science or medicine, Smith’s collection continues to provide clues into the field of chemistry’s past.

“Knowing the history of your discipline helps you better understand the subject you’re studying,” says Farrington. “Scientists today are so focused on current research they don’t generally take time to understand how they got to where they are today, let alone consider whether ideas from the past may deserve reexamination in light of current knowledge. Understanding the arguments, the discoveries, all the ways in which the discipline developed over time, is really important.”

Lynne Farrington is senior curator, special collections, of the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts in the Penn Libraries at the University of Pennsylvania.

Erica K. Brockmeier

(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

Jin Liu, Penn’s newest economics faculty member, specializes in international trade.

nocred

nocred

nocred