(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

In the beginning, she had no idea anything was wrong. But after six months of negative pregnancy tests, Kathleen O’Neill soon found herself in the same situation she was already counseling many patients through. O’Neill was at that time a fellow in reproductive endocrinology and infertility at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP), and she was ready to start a family, just as she has helped many other women start theirs. Like many of her patients, O’Neill would be able to have children but not the way that most women do. O’Neill now hopes the same will be true for a select few patients she sees in a groundbreaking clinical trial of a relatively new technique: uterus transplant.

O’Neill, today an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Penn Medicine, serves alongside Paige Porrett, an assistant professor of transplant surgery at Penn Medicine, as a principal investigator of the trial. Their study is particularly remarkable because it not only offers hope to women unable to give birth because they lack a functioning uterus. It also nestles wonder within wonder: transplanting a functioning organ into a place where one is in many cases missing altogether, then applying a separate feat of medical science to coax new life into the world from that organ. And in an area where numerous fundamental mysteries remain—because highly intensive human study is so rarely practical—it also shows promise of delivering a world of new discoveries about how the body achieves pregnancy and birth, through a deep look at the biological basis of human reproduction.

In the months that followed O’Neill’s diagnosis of unexplained infertility, she went through two cycles of in vitro fertilization (IVF). In a typical IVF cycle, multiple eggs retrieved from a woman’s ovaries are combined with sperm in a laboratory to create embryos. The embryos will grow for several days in the lab before being transferred to the woman’s uterus.

As many as 1 million babies have been born in the U.S. since 1981 with the help of fertility treatments like IVF, but success rates vary. Depending on her health and age, a woman may have to undergo several cycles of IVF before becoming pregnant. O’Neill’s first cycle of IVF ended in miscarriage; the second led to the healthy birth of her now four-year-old son.

“I was seeing patients who were going through IVF and miscarrying, and at the same time I was going through it myself. It was very surreal,” O’Neill recalls of the events of 2013. “But eventually I thought, maybe this is good; maybe this is going to make me a more empathetic doctor and I'll understand more about what these patients are going through. And I think, in a lot of ways, it did.”

When counseling women about their options in her current role in Penn’s Fertility Care practice in Philadelphia, O’Neill now draws from her own experience to offer patients words of encouragement and reassurance: “We might not be able to help you have a baby the way you initially planned to, but we can help you build a family.” She has performed hundreds of reproductive surgeries and IVF procedures.

For women with uterine factor infertility (UFI), the options currently available to achieve parenthood are adoption and IVF in combination with surrogacy. Women living with UFI are unable to birth a child either because they have been born without a uterus, have had a uterus surgically removed, or have a uterus that does not function—conditions that affect 1.5 million women worldwide.

While she’s grateful to have options to offer women who have UFI, O’Neill says adoption and surrogacy have their limitations: IVF and surrogacy can often cost from $90,000 to $150,000, a price that many women simply can’t afford. Adoption costs can likewise run into the tens of thousands of dollars and may not be an option for all would-be parents. O’Neill also notes that neither adoption nor surrogacy offer what many of her patients seek. “Many of the women I talk to, they want to experience a pregnancy; they want to know what that feels like,” she said. “So, I was really excited when uterus transplantation came along as another option.”

A uterus transplant is a surgical procedure that involves a healthy uterus (usually donated by a living donor) being transplanted to a woman who has UFI. In 2017, O’Neill, Porrett, and co-investigators, including Eileen Wang and Nawar Latif, launched the Penn Uterus transplantation for Uterine Factor infertility (UNTIL) Trial. The multi-year trial will offer women with UFI their only chance to carry a pregnancy.

The UNTIL trial shows great promise both for the participants and for future research of women’s health issues. But the concept of uterus transplantation is still relatively new, and thus has its detractors. Criticisms include health risks women must face (two years of tests and high-risk surgeries) and the financial burdens they might experience in the future if the procedure is brought out of trials and approved for regular clinical use (projected costs in the range of $200,000-300,000).

At its core, uterus transplantation has reignited an age-old debate over a woman’s right to choose what she wants to do with her body, and it has reopened political discussion about whether insurers should cover the costs associated with treatment of infertility—a condition that until recently was not even recognized as a disease by the American Medical Association.

Despite criticism, O’Neill and Porrett believe uterus transplants should be offered in addition to other fertility options, not in place of them; and that the woman should be the one who ultimately chooses what lengths she is willing to go to bear a child.

“It's all about introducing more options, and not saying one of these options is perfect for all women, but saying let's make as many options as possible available for women and let's not judge them based on which option they want to use,” O’Neill says.

“Cost is going to be an issue with any new medical procedure,” Porrett adds. “But if we focus on finding ways to standardize and improve the process, as we get better at it, we may be able to make it widely available to potentially thousands and thousands of women who want this as an option.”

A living friend or family member donated the uterus that was transplanted for all of the successful post-uterus-transplant births reported in Sweden and U.S. to date. In the Penn trial, however, O’Neill and Porrett’s team may perform uterus transplants from either deceased donors or living donors, depending on availability and the preference of the individual woman receiving the transplanted uterus.

Penn’s trial is particularly unique for its intensive focus on research. Porrett, O’Neill, and their colleagues are not only joining the ranks of the pioneers of this surgical technique in hopes of establishing it as a safe and effective option for more patients; they are pairing that effort with a comprehensive, multidisciplinary effort to better understand how the body handles pregnancy—whether or not that pregnancy results from a uterus transplant or more established infertility treatment, and whether or not the pregnancy is healthy.

No matter what they achieve, clinically or in research, the process won’t be easy.

No pregnancy is ever simple.

Nearly 4 million babies are born in the U.S. each year, yet there is still so much that remains unknown about what happens in a woman’s body during and after pregnancy. Beyond the more commonly understood physical changes like stretchmarks and newly formed breast tissue, an unknown number of biologic and immunologic transformations occur in a woman’s body during pregnancy.

There are many differences between traditional organ transplantation and uterus transplantation. While kidney, heart, and other organ transplants are permanent procedures used as life-saving measures for individuals with terminal diseases who are often older, uterus transplants are not a medical necessity. They are temporary and are typically performed in young, healthy women who do not have a lot of other medical problems. The goal of a uterus transplant is to achieve pregnancy and birth. After a successful birth, the woman undergoes a second surgery to have the donated uterus removed.

Having that personal experience, understanding that desire to have a child, and now learning more about the struggles women with infertility face, it just makes me that much more motivated to help them.

Paige Porrett, an assistant professor of transplant surgery at Penn Medicine

Successful organ transplantation requires the use of immunosuppression medications to allow the body to tolerate the donor tissue by preventing their immune system from fighting it off as a foreign invader. Traditional organ transplant patients are required to take immunosuppression drugs for the rest of their lives. In uterus transplantation, because the organ is eventually removed, patients will take these drugs for only a finite amount of time—typically two to five years.

Studies of uterus transplants date back to the early 1960s, when doctors first tested the procedure in animal models. This work would eventually lead to the first successful live birth in a mouse model in 2003. In 1999, doctors at Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg in Sweden began preliminary research of living donor uterus transplants in humans. More than a decade later, in 2012, news of the Swedish team’s first successful transplant caught the attention of many in the medical community, including O’Neill and Porrett, who viewed the procedure as a promising, new option for some women living with infertility. Two years later, in 2014, the Swedish team achieved its first successful live birth from a uterus transplant patient. Since then, uterus transplants have been attempted in humans at least 40 times. A total of 12 babies have been born to women with uterus transplants worldwide; the majority of them in Sweden and, recently, two in the United States. But excitement has been tempered by many failed transplants. O’Neill, Porrett, and their team are out to accelerate progress in the field.

During pregnancy, a woman’s body accommodates a number of complex changes; her heart pumps more blood; her body changes how it metabolizes food; her uterus expands to roughly 500 times its normal size; her joints soften; her sense of smell improves; and then, in almost miraculous fashion, when the baby is born the body naturally returns to its pre-pregnancy state.

However, it is still unclear how many of the physiologic changes of pregnancy may persist into postpartum life. And the tremendous changes that occur to a woman’s immune system may alter her body’s functions forever.

The immune system’s changes during pregnancy are their own special mystery. The primary function of the human immune system is to identify foreign cells and tissues (invaders) in the body and launch an attack to remove them. Because a fetus is made up partially of its father’s genome, making it biologically different from the mother’s body, the mother’s immune system should identify the fetus as a foreign invader and expel it. During pregnancy, however, a woman’s immune system somehow tolerates the fetus despite its “foreign” status. How this occurs exactly remains unknown.

Much of Porrett’s training has focused on the phenomenon of immunological tolerance during pregnancy and other biologic consequences of pregnancy—though, as a transplant surgeon, women of childbearing age don’t make up a large share of the patients that she treats. After earning her medical degree from Northwestern University in Chicago, Porrett came to Penn for a doctorate in Immunology (completed in 2008) and residency in surgery (2010), followed by a fellowship in transplantation surgery (2012). Porrett has long been intrigued to learn whether and why women who have been pregnant in the past experience worse kidney transplant outcomes. Porrett is actively investigating whether the immunologic mechanisms that permit tolerance of a fetus during pregnancy are remembered by a woman’s immune system in later life. Now, in studying uterus transplantation, her challenge is to understand an unusually complex pregnancy scenario where the woman’s immune system must tolerate the immunological differences of both the organ donor and the fetus.

Porrett is also a mom, and she says her journey to motherhood helped drive her interest in leading the trial.

“I came to be a mom relatively late in life; I did not want to have a baby for a long time and then later, I changed my mind. I’m so glad that I did because it’s one of the greatest things that ever happened to me,” she says. “Having that personal experience, understanding that desire to have a child, and now learning more about the struggles women with infertility face, it just makes me that much more motivated to help them.”

A successful uterus transplant and birth is a massive undertaking.

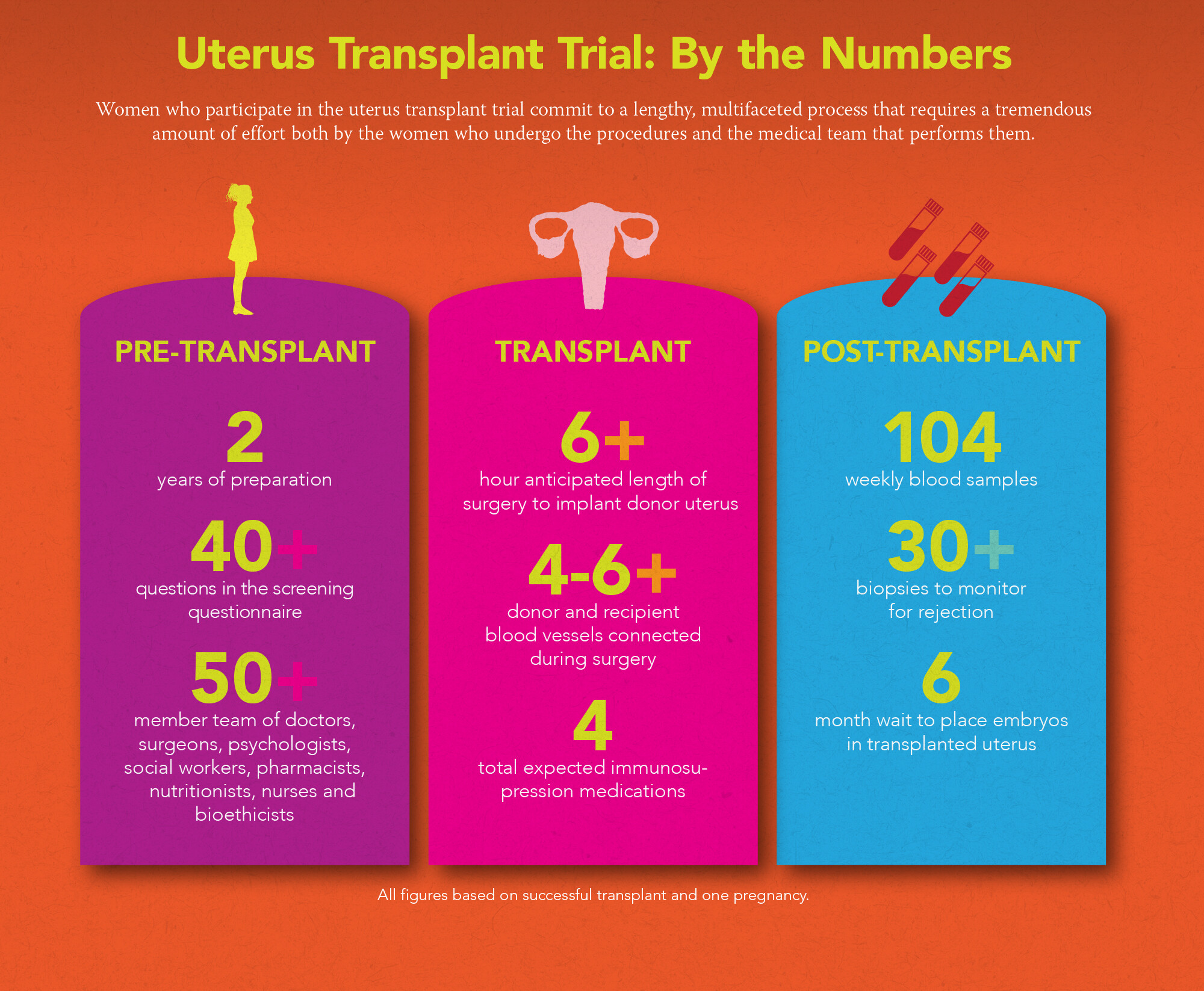

The UNTIL trial will pool the expertise of a 50-plus member team of doctors, surgeons, psychologists, social workers, pharmacists, nutritionists, nurses, and bioethicists who will help guide transplant recipients through as many as 150 medical procedures ranging from urine and blood analyses to ultrasounds, cervical biopsies, and surgeries.

While there are many medical visits in the course of a typical healthy pregnancy—roughly 15 times over 40 weeks, encompassing seven or more prenatal check-ups and screenings—women participating in the UNTIL trial will be monitored far more intensely before, during, and after pregnancy. They will have weekly visits for at least two years, and will submit more than 100 blood samples, over 30 urine samples, and undergo more than two dozen cervical biopsies over that two years. From pre-transplant evaluation to final follow-up after up to two births, a uterus transplant patient’s course can take anywhere from 16 to 24 months. This intensive prenatal screening schedule will help ensure the safety of mom and baby throughout transplant, pregnancy, and delivery. The detailed surveillance also gives doctors the unique opportunity to gather data for future research that may help improve other infertility treatments.

We’re going to gain tremendous knowledge from this trial... It’s uncharted territory.

Co-investigator Nawar Latif

Candidates for the UNTIL trial must be women with UFI between the ages of 21 and 40 who don’t smoke and are in general good health. Potential candidates are required to complete an initial questionnaire and undergo an extensive health screening through which researchers will assess everything from physical health to social support systems.

Experience is an equally important component for success in uterus transplantation. Penn is one of only three centers in the U.S. that currently offer uterus transplants to women with UFI.

O’Neill is an expert in reproductive endocrinology and infertility. A graduate of the University of Michigan Medical School, her training includes a residency in obstetrics and gynecology at Barnes-Jewish Hospital of Washington University in St. Louis, a fellowship in reproductive endocrinology and infertility at HUP, and a master’s degree in translational research from the Perelman School of Medicine at Penn.

Her expertise is an ideal complement to Porrett’s background in transplant surgery and immunology.

Together, and with the rest of their collaborators, O’Neill and Porrett are well positioned to take the many measurements of a quantified pregnancy and translate that into a wide range of advances in understanding of how pregnancy occurs, how it changes women’s bodies, and how to treat many rare and common complications.

As their co-investigator Nawar Latif, an instructor in gynecologic oncology notes, “We’re going to gain tremendous knowledge from this trial about anatomy, surgery, perfusion of the uterus, and other organs. Obstetricians will also learn a lot about transplant and pregnancy, and how we can better manage those situations. It’s uncharted territory.”

Consider the placenta. This fascinating organ temporarily grows in a woman’s uterus and is expelled after pregnancy. In addition to providing nutrients and oxygen to the fetus and removing fetal waste through the umbilical cord, the placenta transfers antibodies from the mother that provide immune protection for the fetus.

As Porrett explains, the placenta comes into contact with various tissues in the uterine wall, including immune system cells which would normally come from the mother, but in the setting of a uterus transplant, these cells are derived from the donor. As the placenta matures while the fetus grows, the fetal immune system is also developing and growing, but researchers still do not know exactly when some of the earliest immune precursors occur in the fetal blood.

“We know the fetus is having an effect on mom and that mom is also having an effect on the fetus,” Porrett says, “but how much of this comes from the local uterine environment and therefore might be influenced by the donor is still unknown.”

I'm thrilled to participate in something that may, to some extent, help raise awareness of infertility and hopefully revolutionize the care of women’s health issues across the board.

Paige Porrett, an assistant professor of transplant surgery at Penn Medicine

As the surgical director of the Living Donor Kidney Program in Penn’s Transplant Institute, Porrett also sees the trial as an opportunity to apply her years of organ transplantation knowledge to a completely new patient population.

In the field of transplantation, immune rejection of the donor’s organ by the recipient is prevented through the use of medications which restrain the immune system. Porrett refers to these immunosuppressive drugs as “highly effective but not specific,” because immunosuppression drugs limit all of the body’s immune responses—not just those that might damage an organ, but also immune cells that are harmless to it and may be required to respond to other threats to the body, such as bacterial or viral infection. But perhaps, Porrett theorizes, research on the immunology of pregnancy could help doctors make immune suppression far more specific. Essentially, she hopes to someday trick the immune system into responding to any donor organ—lung, liver, or kidney—in the same way that it responds to a newly developed fetus during a normal pregnancy. Transplant patients could be spared all the complications that come with immunosuppressive drugs—notably the constant vigilance to avoid exposure to infection because even a common cold could be life-threatening in the face of their bodies’ weakened defenses.

“Nature has solved our problem; the body achieves immune tolerance in pregnancy every single time,” she says. “But we still don't fully understand how. Better understanding of the biologic mechanisms of fetal maternal tolerance could completely revolutionize the way we immune manage our patients because the body is capable of doing this. We just have to figure out how to influence it to do so.”

The UNTIL trial will give researchers unprecedented access to observe and screen multiple women during these early stages of pregnancy, possibly allowing them to uncover new information about when and how the fetal immune system is formed.

The trial may also help improve understanding of some of the most common complications that occur during pregnancy and transplantation.

Thrombosis (blood clotting) and preeclampsia (high blood pressure during pregnancy) are two of the more common complications that occur in pregnancy as well as in uterus transplantation, but doctors do not yet know much about why either occurs—even though these conditions can be life-threatening to both mother and baby. Porrett estimates thrombosis occurs in roughly 30-40 percent of uterus transplants. According to the Preeclampsia Foundation, approximately 5 to 8 percent of pregnancies are affected by preeclampsia, a disease thought to occur because not enough blood flow reaches the placenta, thereby limiting the amount of oxygen and food that reaches the fetus. This ultimately results in low birth weight.

Obstetricians see preeclampsia and eclampsia in women from all over the world but do not yet understand the biologic basis for it. It’s an area of research that trial co-investigator Eileen Wang is excited about exploring through the trial.

“Our field has been plagued by the complications of pregnancy; one is preterm birth and the other big category in terms of number and frequency is hypertensive disease in pregnancy or preeclampsia,” explains Wang, the director of obstetrical ultrasound in Penn Medicine’s Maternal Fetal Medicine Program. “I think it’s a big arena to explore because right now we don’t have a lot of good answers.”

As Wang explains, women who enter pregnancy with vascular conditions such as hypertension, long-term diabetes, or lupus have a much higher risk of preeclampsia. Through the trial, researchers will be able to observe healthy women as a comparison. By monitoring blood flow to the uterus multiple times throughout the trial, researchers may learn how to improve the blood flow to that organ and reduce the risk of preeclampsia.

Porrett says knowledge gained from the trial will be crucial to helping researchers address these and other complications to make uterus transplantation safer and more accessible, as high thrombosis and preeclampsia rates are major barriers to offering uterus transplant therapy more broadly. She’s also hopeful that the trial will help change the way women’s health issues are viewed and treated for years to come.

“Ultimately, these women are enabling us to study something that is very abnormal so that we can understand something more about what is normal,” Porrett says. “I'm thrilled to participate in something that may, to some extent, help raise awareness of infertility and hopefully revolutionize the care of women’s health issues across the board.”

At the time this article published, more than 100 women from more than 25 states have entered the screening process for enrollment in the Penn trial. The UNTIL trial is still enrolling patients. For more information, visit http://www.whcrc.upenn.edu/uterine-transplantation.

This article was originally published in the Fall/Winter 2018 issue of Penn Medicine Magazine.

Homepage photo: Penn Medicine’s Kathleen O’Neill, an assistant professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology (left), and Paige Porrett, an assistant professor of transplant surgery, are co-principal investigators of the multi-year Penn Uterus transplantation for Uterine Factor infertility Trial (UNTIL), which offers women with uterine factor infertility a chance to carry a pregnancy. The procedure shows great promise both for the participants and for future research of women’s health issues, but the concept of uterus transplantation is still relatively new. (Photo: Peggy Peterson)

Queen Muse

(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

Jin Liu, Penn’s newest economics faculty member, specializes in international trade.

nocred

nocred

nocred