(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

One word in a barely legible phrase written in faded ink caught the eye of Penn Professor Joan DeJean when she came upon the file for a woman imprisoned in Paris more than 300 years ago. As she paged through archives at the Arsenal Library in France looking for someone arrested in 1719, she paused when she saw “et autres prisonnières de la Salpêtrière pour la Louisiane” underneath the name “Fontaine (M.-A.).”

The translation: “and other female prisoners in the Salpêtrière (prison) for Louisiana.”

DeJean, a Trustee Professor who taught French and Francophone studies in the School of Arts & Sciences for 33 years, was born and raised in Louisiana, the last in her family’s lineage to speak both French and English. She had spent decades reading through files at the long wooden table in that archive in Paris, looking for a clue just like this one.

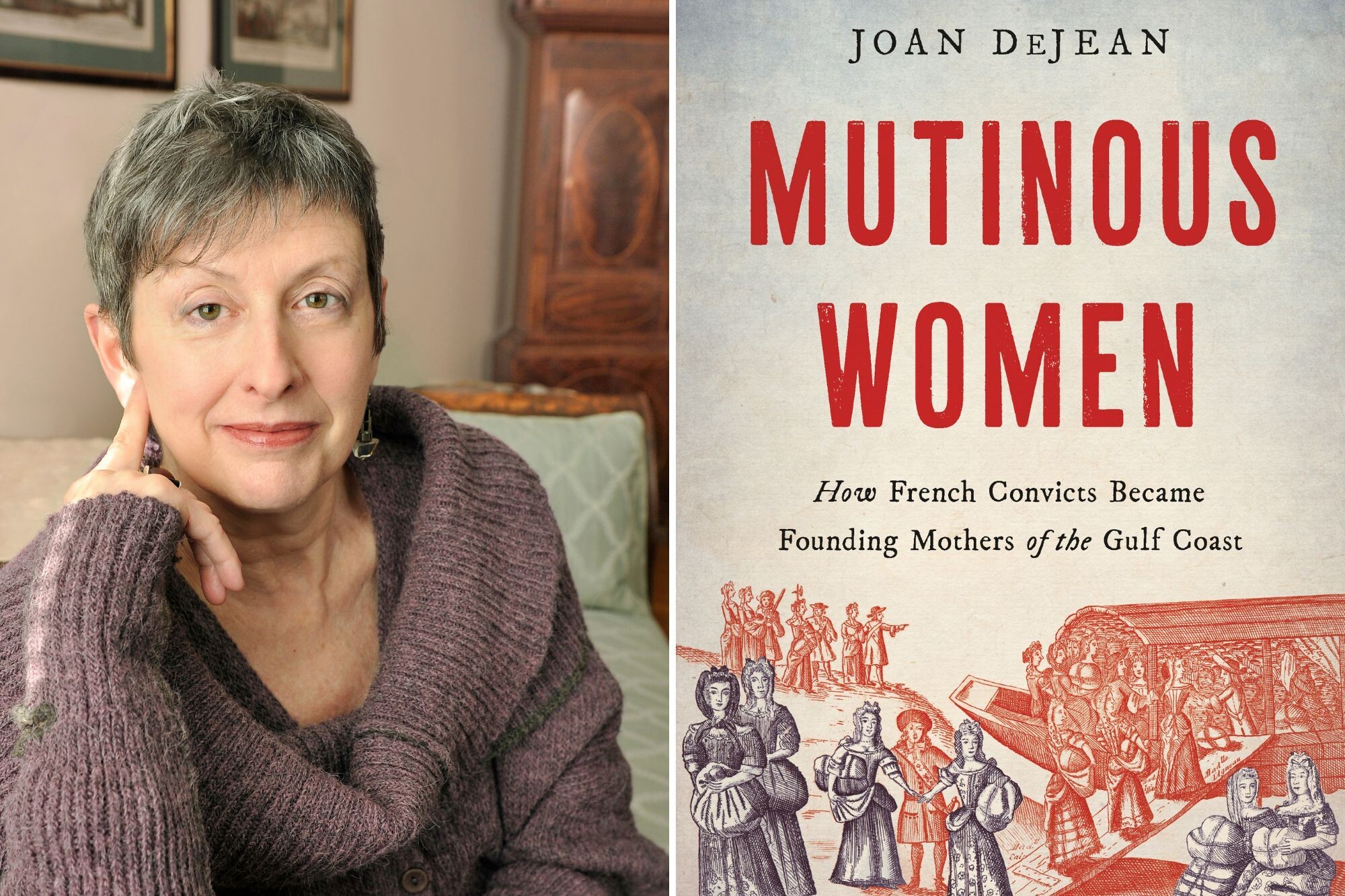

“Louisiana, that’s where it started. If I hadn’t been from Louisiana, I wouldn’t have opened that file, and I wouldn’t have seen the list of the women,” she says, women who became the focus of her research for the next 10 years, starting with Manon Fontaine, and culminating in DeJean’s latest book, “Mutinous Women: How French Convicts Became Founding Mothers of the Gulf Coast.”

The book has received quite a bit of attention, including reviews in the The Wall Street Journal, Time Magazine, and the New York Times, and on WWNO in New Orleans, as well as an interview with the Fédération des Alliances Françaises USA.

“These are truly remarkable figures, and I want their descendants to be proud of them,” DeJean says. “My biggest hope is that the descendants, as many descendants as possible, will find the book and that they will understand that they have wonderful ancestors.”

In December 1719 a ship, named La Mutine, or the Mutinous Woman, departed France carrying a cargo of convicts, the only all-female roster of deportees to what would become the United States, Fontaine among them. Most of the 132 women were illiterate peasants, most wrongly accused with no evidence of a crime, most labeled as prostitutes.

Abandoned by their nation, they arrived at a nascent European settlement with newfound freedom and seemingly impossible challenges, becoming pioneers who built New Orleans and French trading outposts and settlements along the Mississippi River.

Through investigative research in unexplored corners of archives in France, DeJean has documented and corrected these women’s stories, discovering that they were not prostitutes, thieves, or murderers, as accused, but instead victims of corruption. Ultimately, they were survivors.

Since publication, people, including a Penn graduate, from throughout the country—from California to New Jersey, Texas to North Carolina — have contacted DeJean, saying they are descendants of the women on the ships. “They write and say, ‘Thank you,’ because they didn’t know the true story,” she says. She was even invited to a gathering of descendants of Anne Francoise Rolland at a pig roast and Cajun music festival in Louisiana this summer.

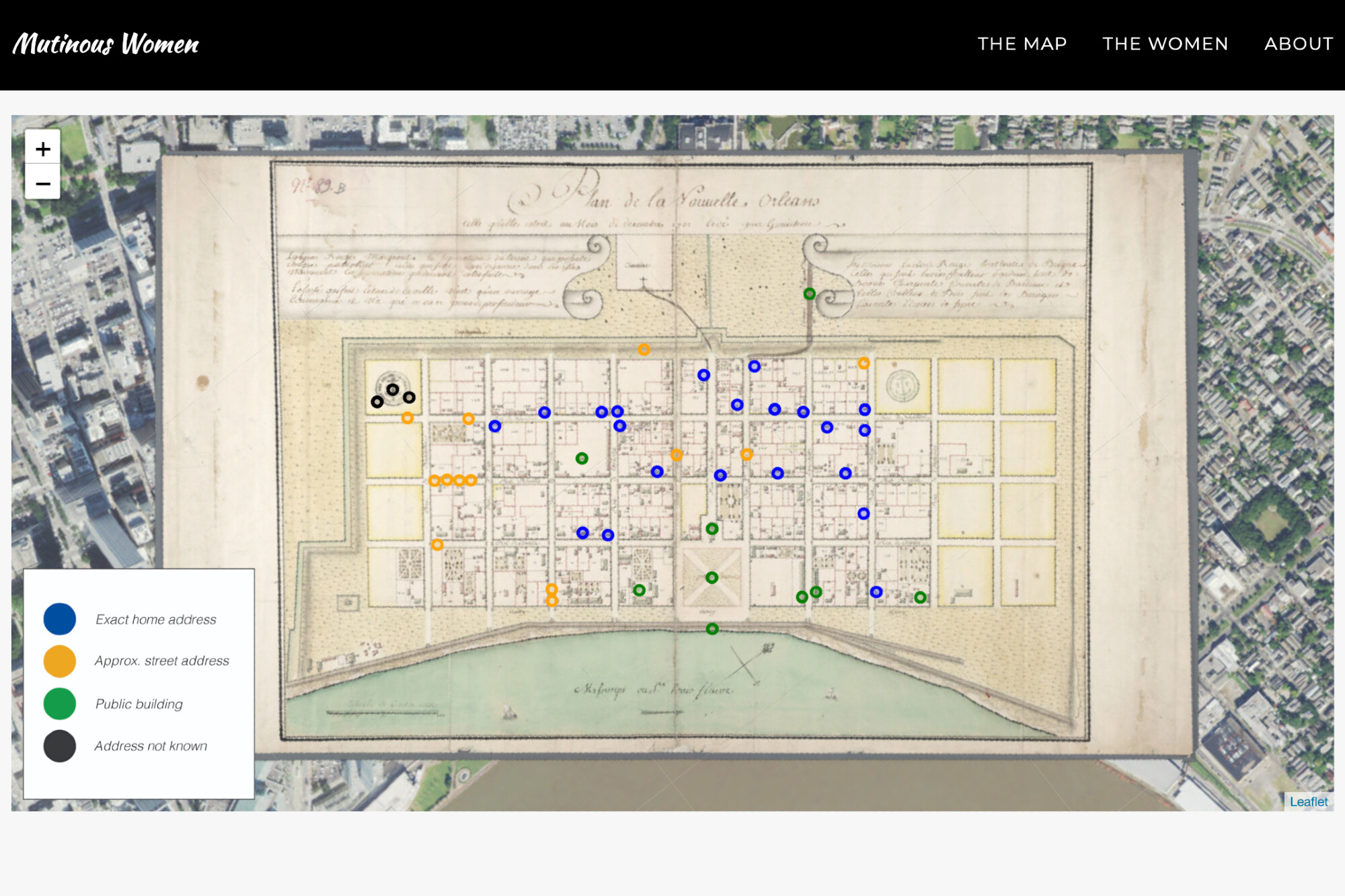

DeJean worked with the Price Lab for Digital Humanities to create an interactive digital map of where some of the women settled, using a 1731 map of New Orleans. By clicking on the numbered plots, users can read the biographies of 37 of the women who lived there.

Despite her family’s long history in Louisiana, DeJean is not herself is not among the descendants. “I kept worrying as I went through this that I would discover that I was a descendant, and that I didn’t want, because I thought then my outrage would seem personal,” she says.

However, DeJean did discover that one of her ancestors, Jean Gradenigo, witnessed the women’s marriages as they regained their status, finding their footing in their new world. DeJean grew up where some settled, in southwest Louisiana.

“As a child, I spent days on end with my paternal grandfather, a true Cajun, in his dugout canoe,” DeJean wrote in the book’s Coda. “I was once perhaps as comfortable in the bayous and the wetlands of that strange and fragile landscape as many deported women had grown to be over two centuries earlier.”

Traveling far from the bayou, DeJean made her career on Ivy League campuses, teaching French and Francophone studies at Princeton and Yale universities before joining Penn’s faculty in 1988. She retired from teaching last year.

DeJean is the author of 12 books on French literature, history, and material culture of the 17th and 18th centuries. She was researching “The Mutinous Women” at the same time as she was researching her 2018 book “The Queen’s Embroider: A True Story of Paris, Lovers, Swindlers, and The First Stock Market Crisis,” also set in 1719 Paris.

Along the way she learned the intricacies of the French financial records, as well as how to recognize police and political corruption. “You can tell the two books fed each other,” DeJean says.

Starting with Fontaine’s dossier in the prison records, DeJean then searched for her in the archive of criminal trial proceedings. “I kept turning pages and turning pages. And there was Manon Fontaine,” she says. “The false claims in the trial records matched with the dates for the arrest. It was really her. So that’s when I knew I had a book.”

The lawyer who pursued Fontaine “was the greatest legal mind of the 18th century in France, and was personally invested in trying to nail her,” DeJean says. “So everything was saved, every verdict, everything.”

The book starts with the details from the 1701 trial of Fontaine, an illiterate teenaged street vendor who sold fruit from a basket strapped around her waist. She was accused and convicted of murder, with dubious witnesses and no credible evidence, even though she had an airtight alibi. She spent 18 years in prison. “It’s all there,” DeJean says of the archives.

DeJean researched the prison records and trial proceedings of the other women shackled together on that ship in December 1719 and followed the paper trail to learn their fates. Often they were sold out by their own families, considered financial burdens.

Repeatedly on key documents DeJean would find similar phrases: “to rid the Salpêtrière of female prisoners,” or “to transport women to the islands,” reading allegations she says were “patently ludicrous” that went unchallenged and became even more inflated.

“This just happened to be this conjunction of factors, the financial crisis, the need to get money quickly from France, huge police corruption, all of this together at that time made it possible,” DeJean says. “I tabulated all the arrests for prostitution and the change of vocabulary in this period; they were going after women in a major way. And they just decided it’s prostitution. Anything became prostitution. Yet those who would’ve been seeking their favors were not prosecuted.”

DeJean says she has developed a “certain distrust” of law enforcement after working in the police archives of 18th-century Paris for decades. “I know the period, and I know about the police corruption. So I went in with a doubting angle. Because of the ‘Embroider’ book, I knew how to trace families financially. And that hadn’t been done before with these women,” DeJean says. “So that’s how I could tell when there was poverty, when there were desperate circumstances.”

While their ship, La Mutine, was on the Atlantic the Paris Stock Exchange crashed. In the financial chaos, they were forgotten by the authorities who sentenced them to the journey and banishment.

During her research DeJean would become outraged as she discovered the women’s fates. Writing in a half-French/half-English shorthand, she would bang her fist on the wooden tables. “I would get so mad. I would bam [hitting the table], hurting my hands, when I couldn’t stand it,” she says. “Sometimes I’d go bam [hitting the table again] with both of them and everyone would look.”

Once the women crossed the Atlantic, only one mother tried to find her daughter, and only so she could collect an inheritance. “These were the things that just broke my heart. Daughters, women, had so little value, especially in poor families,” DeJean says. “There was poverty, but nonetheless, to give up your daughter to let the police frame her? Yes, I felt outrage.”

Some of the women she could not trace once they reached U.S. because records read simply “plus wife,” DeJean says. “I keep wondering that “plus wife” could it be one of the women? There could be other survivors,” she says.

DeJean says she believes the women constantly supported one another. “They were chained. I traced them. I knew their numbers, so Number 69 would have been chained to 70, etc., and so often friendships followed with those numbers. They must have really been there for each other through the worst moments,” DeJean says.

“And every time I found a will, one of them would list another, noting that one had lent her money. They were continuing to look out for each other. New Orleans was big, but it was small. They would see each other all the time.”

One of those was the flower girl Fontaine, a loyal friend who loaned money and extended credit to her fellow former prisoners, DeJean says. Although she remained illiterate, her signature an “X” on the documents DeJean found, Fontaine married a blacksmith and became one of the founding residents of New Orleans. By the time of her death in 1734, she owned five properties in today’s French Quarter.

DeJean says she considers herself to be a witness, her book a way, as she writes in the conclusion, “to attest to the true identities of the deported women, to the fact that the identities recorded for them by the French judicial system were fabrications designed to serve the interests of a society corrupted by financial greed and to the lives that survivors built against all odds in places that, as girls in France, they could never have imagined.”

Louisa Shepard

(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

Jin Liu, Penn’s newest economics faculty member, specializes in international trade.

nocred

nocred

nocred