Penn engineers and collaborators have developed a transparent, micro-engineered device that houses a living, vascularized model of human lung cancer—a “tumor on a chip”—and show that the diabetes drug vildagliptin helps more CAR T cells break through the tumor’s defenses and attack it effectively.

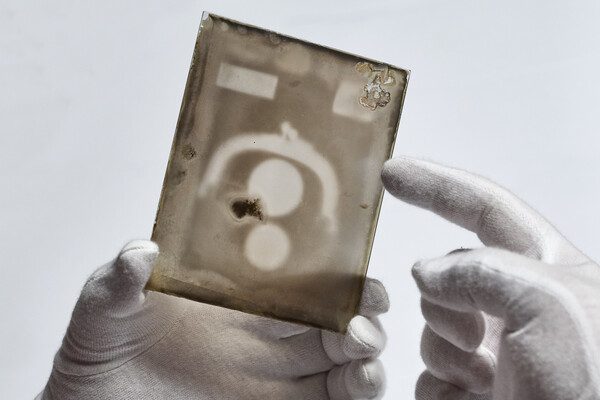

(Image: Courtesy of Dan Huh)