nocred

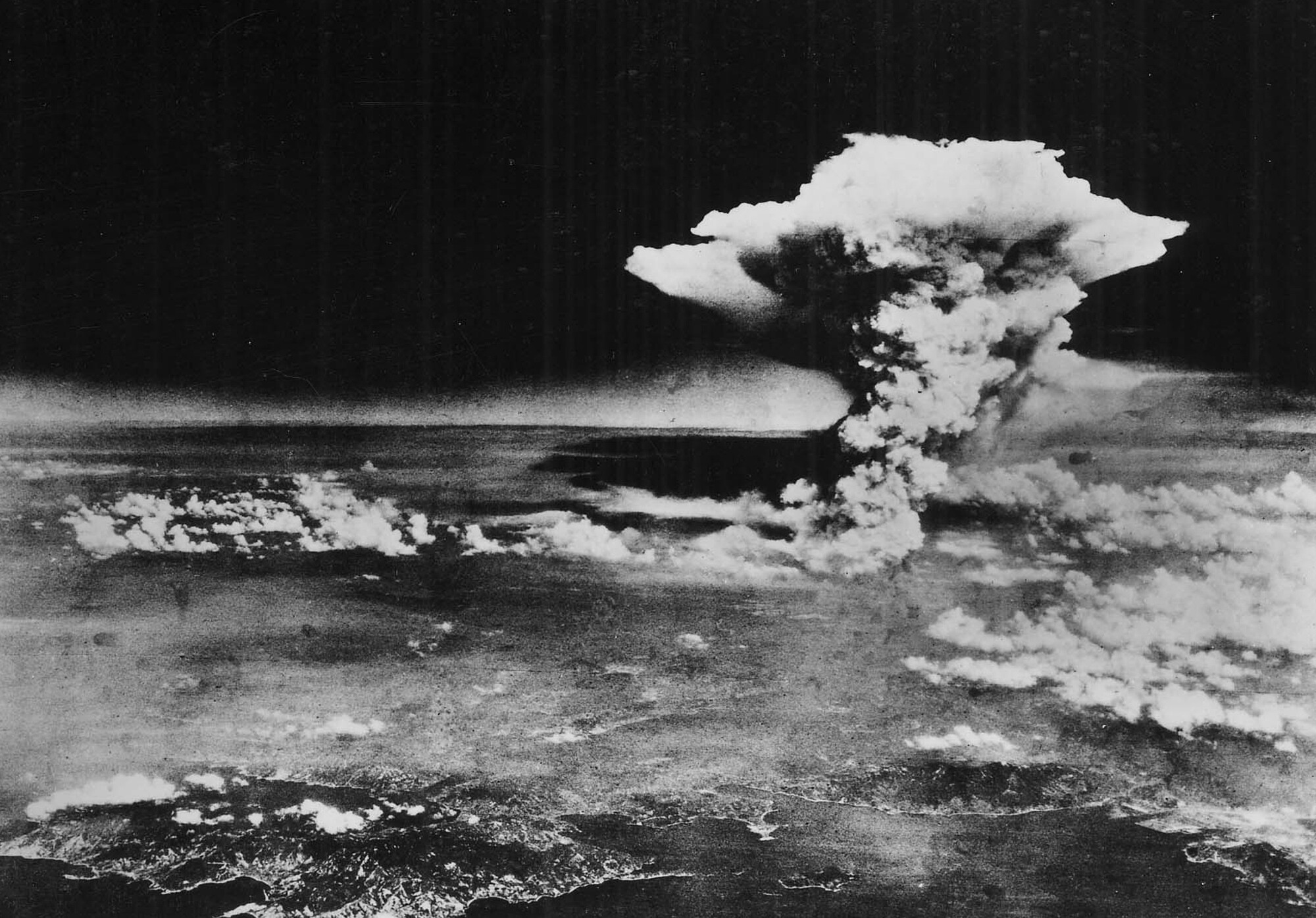

August 6 marks the 75th anniversary of America’s atomic bombing of Hiroshima, the first time a nuclear weapon had ever been used. Three days later, a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, leading to Japan’s surrender and the end of World War II. The two bombs took the lives of more than 200,000 people. Penn Today asked scholars and experts on Japan and nuclear weapons to share their thoughts on the anniversary.

Once upon a time a mayor dared us to unmake the prophecy uttered about Hiroshima post-August 6, 1945: ‘Nothing will grow for 75 years.’ Mayor Akiba Tadatoshi predicted in a 2004 Peace Declaration we could ‘bring forth a beautiful “flower”’ for the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings, namely, the total elimination of all nuclear weapons from the face of the earth.’

It was just a fable. The mayor summoned ‘an anti-nuclear tsunami.’ Instead the 2011 tsunami exposed how the ‘Atoms for Peace’ myth had flourished. Rimming Japan, reactors imperil the coasts for the short-term benefits that Haruki Murakami, the fabulist, excoriated in his Catalunya Speech as ‘efficiency.’

Is there hope? Weeds once returned in no time, barely covering the pain and peril of the city. Words bloomed from eyewitnesses like Tamiki Hara, Yōko Ōta, Sadako Kurihara, and Kyōko Hayashi. These voices speak the unspeakable, yet 75 years after the United States government dropped the only atomic bomb on a civilian population—twice—how many Americans heed them? Young readers may know the anti-war manga series ‘Barefoot Gen,’ but have we seen the Maruki murals, savored Kenzaburō Ōe’s essays or watched the film version of Masuji Ibuse’s ‘Black Rain?’ Now is the time.

Now, as we rewrite our national story, the fables of the past—nuclear deterrence, racism, inequality, climate exploitation—must all be untold. Seventy-five years from today people must say, ‘Once upon a time, nothing grew but lies and misery;’ children must shout ‘No way!’ when they hear that generations had harbored these delusions. This is my view from Japanese literature.

National narratives thrive on tales of victimization, not transgression. China in 1985 built a museum to the 1937 Nanjing Massacre, which Japanese conservatives routinely dismiss as a fabrication. The Hiroshima Memorial Museum opened in 1955 and hosts a large annual commemoration, but the first American president to visit was Barack Obama just four years ago.

Hats off to President Obama for not just visiting but acknowledging the ‘brutal end’ of the Pacific War and acting on a key lesson of Hiroshima. The U.S., Obama declared in 2016, ‘must have the courage to escape the logic of fear and pursue a world without’ nuclear weapons. He cut American nuclear stockpiles by 553 warheads.

Unfortunately, the farther we move temporally from Hiroshima, the less likely we are to act constructively upon its lessons. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe consistently proclaims Japan the world’s only victim of nuclear war to press for a nuclear-free world. Meanwhile, over vociferous public protest, he has dramatically enhanced Japanese military capabilities and reactivated nuclear power plants after Fukushima. Donald Trump now speaks of resuming nuclear testing for the first time since 1992.

Nuclear weapons did not win the war against Japan. As both Tsuyoshi Hasegawa (2005) and Yukiko Koshiro (2013) have cogently argued, a declaration of war by the one power with which Japanese statesmen had hoped to negotiate terms, the Soviet Union, was key. In this context, Hiroshima is less significant as the end of a calamitous war than as the start of what President Eisenhower would decry as a looming American military industrial complex.

Thankfully, since the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, 1945, nuclear weapons have been used only as force held in reserve to back up threats. Nuclear-armed states, unsure they can avoid devastating retaliatory strikes, have refrained from escalating their confrontations involving the use of military force and instead have cautiously managed their crises. The distinctive fear about what could go wrong when nuclear weapons are in play has been such a potent constraint that even the meager arsenal of North Korea has dissuaded an incomparably powerful U.S. from indulging the temptation to launch a disarming preventive attack. The nuclear revolution effectively rendered the old calculus about balances of power and the use of military force obsolete. And yet, ideas once disparaged as ‘conventionalized’ thinking that ignored the stark reality of the nuclear age have reappeared in policy debates.

Does the revival of claims about the plausibility of fighting nuclear wars, a focus on offense and defense rather than deterrence, reflect new technologies that reverse the verdict on the nuclear revolution? Or are they ‘zombie ideas’ whose fatal flaws will again be revealed as today’s analysts rediscover shortcomings identified decades ago but whose relevance has been forgotten? Seventy-five years after Hiroshima, these are public policy questions of overriding importance. Policies rooted in the belief that the old lessons and harsh realities of the nuclear age no longer pertain will increase the ever-present risk of instability during a future crisis.

Although one might hope that the old fears about what could go wrong make it likely that caution would kick in and catastrophic conflict would be averted, there are no guarantees. In this regard, another lesson from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima should be recognized: When wars start, one can never be sure where and how they will end.

The 75th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima is an opportunity to reflect on one of the most important events in world history. Marking the dawn of the nuclear age, Hiroshima still resonates with us today because the threat of nuclear devastation first seen there remains with us as well.

While the world stepped back from the nuclear brink in the latter part of the Cold War, the technology cannot be put back in a bottle. Countries around the world, including the United States, still possess this capability and are working to modernize their nuclear arsenals for the 21st century. Even as the practical realities of geopolitics mean this is likely to continue, it is ever more important to recognize the horrific human toll of warfare and the very real lives, families, and consequences at stake.

We each have a responsibility to learn, to remember; those involved in decision making about the use of force have an even bigger responsibility not to look away. Hiroshima is our history and our responsibility; we must never forget what that means.

“Unforgettable Fire” is the title of a book of drawings and paintings by atomic bomb survivors that presented their visual memories of the hours and days after the bombings. These artistic creations provide one way of understanding an experience that occupies a special place in geography, time, and history.

Some have suggested that the two cities were bombed as experiments. I would suggest that if Hiroshima and Nagasaki were experiments, then so, too, were Dresden, Berlin, Hamburg, and Tokyo. Destroyed cities in World War II were sites for scientific knowledge production, what I call collateral data. Like other bombed places, Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the focus of significant scientific research, by physicists, geneticists, psychologists, botanists, physicians, and other experts.

Even 75 years later, Hiroshima and Nagasaki are still the only two cities to have been subjected to nuclear attack in wartime, and the United States is still the only nation to have used nuclear weapons in active, declared war. Had they been firebombed like almost every other city in Japan, their names would not be shorthand for anything. They would have been burned and destroyed as were Tokyo, Yokohama, Iwakuni, Nagoya, Kobe, Matsuyama, and Osaka. Instead, they have come to symbolize almost a break in time. As we contemplate this break in time today, we contemplate a shift into a post-nuclear world made by some of the finest minds of the 20th century, the scientists and engineers who built a machine that could in theory destroy all human life—an unforgettable act of brilliance and heedless stupidity.

What made the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki possible? Military buffs might answer this question in terms of technological capacity. Grand strategists may debate whether the bombings were inevitable or justifiable. But we must consider how it even became conceivable for Americans to deploy such weaponry against their fellow human beings. The answer is disturbing because the same logic remains in operation today.

The use of atomic weapons was a logical extension of the dehumanization of the Japanese enemy in American media. Posters likened Japanese people to vermin in need of extermination. Magazines depicted rapacious Japanese soldiers kidnapping blonde American women. Long before the atomic bombs fell, these images rationalized the indiscriminate firebombing of nearly every Japanese city. The results were devastating. For example, at least 100,000 civilians died during a single raid on Tokyo on March 10, 1945. Many more died in subsequent raids. The atomic bombs added harsh insult to grievous existing injuries.

Today Japan is our ally, not our enemy. But U.S. political leaders still portray foreign ‘Others’ as subhuman monsters. The technologies have changed. Drone strikes and border cages are not as visually arresting as mushroom clouds. Indeed, we’re not supposed to see them. But body counts still rise, and innocent noncombatants remain the ones who suffer most.

Kristen de Groot

nocred

nocred

Despite the commonality of water and ice, says Penn physicist Robert Carpick, their physical properties are remarkably unique.

(Image: mustafahacalaki via Getty Images)

Organizations like Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships foster collaborations between Penn and public schools in the West Philadelphia community.

nocred