nocred

Handwritten in black ink is an original working draft of a poem, “Going Somewhere,” penned by Walt Whitman in 1887, some words crossed out, others added, scrawled on the back of a discarded note.

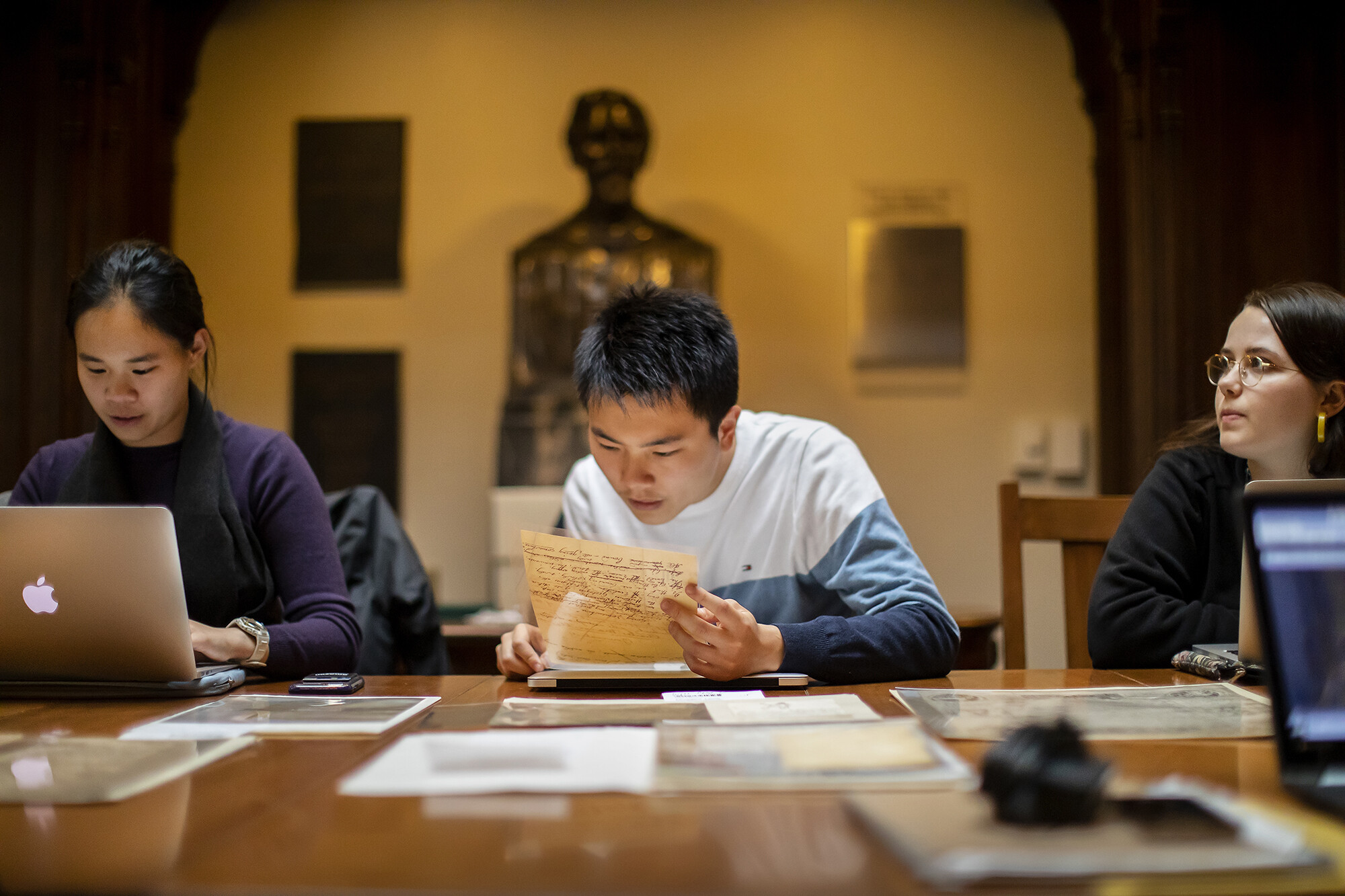

Holding the fragile sheet of paper protected in a clear sleeve is Huilin “Kelly” Liang, a Penn sophomore from Hong Kong. She is a vice-president of the Penn Manuscript Collective, a group of undergraduates who meet every other Friday to transcribe originals in the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts.

“Having access to all these original manuscripts, and actually holding them in your hands, is so different. It feels like you are actually accomplishing something, not like just seeing it on a laptop,” Liang says.

On this particular Friday, the students are focused on Whitman’s work in anticipation of this year’s celebration of the 200th anniversary of his birth. Their work deciphering the handwritten words of Whitman and his circle will be presented during a March 29-30 international symposium, Whitman at 200: Looking Back, Looking Forward, at the Penn Libraries, which holds a significant Whitman collection.

Whitman, who lived the last 20 years of his life and is buried in Camden, N.J., regularly crossed the Delaware River on the ferry to visit friends and do business in Philadelphia. The Libraries is the lead institution behind Whitman at 200: Art and Democracy, a region-wide series of exhibitions and cultural events meant to reassess Whitman and examine his impact on art and society.

The Libraries’ Whitman Collection includes books, manuscripts, documents, correspondence, photographs, and objects by and about Whitman, as well as rare first-editions of Whitman’s publications.

Lynne Farrington, senior curator of special collections and project director for Whitman at 200, writes: “The collection provides a picture of the tremendous forces that shaped public and scholarly reception of Whitman’s work, forces that ensured the poet’s entry into the canon of American literature.”

These rare materials are available upon request at the Kislak Center in the Libraries. Students and faculty regularly make use of primary documents there.

“There is no way you could do this virtually anywhere but at Penn. Certainly never to touch them—that’s extremely unusual, certainly for undergraduates,” says Peter Stallybrass, emeritus professor of English, comparative literature, literary theory, and the humanities. “Everybody here has access to original manuscripts.”

Stallybrass oversees the Manuscript Collective, along with John Pollack, a Kislak Center curator. Founded in 2015, the group publishes a blog and a journal of its transcriptions.

When the group last met, on the last day of November, several Whitman papers are in the center of the polished-wood conference table in the historic Lea Library. The books are open, supported on foam wedges, the many single sheets protected in clear sleeves.

While transcribing, the students work from a digital image projected on a screen to make it easier for everyone, collectively, to decipher the words on each line, reading them aloud as the group’s president, Yuxin “Vivian” Wen types the transcription into her laptop.

“A group like this which is all about the physical connection to materials is also very reliant on digital tools to make the process work,” Pollack says. “We’ve got pictures, and digital versions online, and we magnify the digital images on the screen. We create Google docs for everyone to share.”

They work through Whitman’s writing in “Going Somewhere,” written on the back of a crossed-out letter, folded twice, sent to Whitman from a journalist and autograph-seeker, Charles Marseilles, and dated April 18, 1887.

The students take turns reading out each word, noting capital letters, and every comma, apostrophe, and period, specifying what was crossed out and replaced.

“‘My’ is crossed out, for ‘a’ before ‘memory.’ But if you look up above, it is the other way, he’s crossed out ‘a’ and put ‘my.’ So he’s going back and forth,” says Stallybrass. On the same line, “word” is crossed out after “memory” and “leaf” is written in above.

“I think there are three stages: first, writing below; then writing above; and then squeezing it in here and here,” Stallybrass continues, noting that this document is probably an early draft. “He’s at this experimental stage where he’s not sure where all of these are going yet, and he’s shoving words around.”

Henry Hung, a sophomore from Hong Kong who is majoring in philosophy, reads the last line: “All, dash, insert, surely, going somewhere, all underlined, period, end quotation marks,” he says aloud to the group.

Whitman was trained as a printer. Nicole Hartland, a junior history major who is an exchange student visiting from Queen Mary University of London, reads Whitman’s instructions written on another of his works displayed on the table: “Please set this up in the usual way usual time & let me see a proof this evening or to-morrow morning.”

“He is thinking about how, quite literally, it will look on a page,” Stallybrass says. “The comments he is making, these are really fascinating to have.”

The group then examines a printed version of “Going Somewhere,” signed by Whitman. The students compare the two versions: one typeset, one handwritten. “It’s a fabulous thing to have the draft, and the printed version, too,” Stallybrass says.

“There is a strange sense of intimacy with physical objects,” says Wen, a junior from China who is majoring in comparative literature, explaining why she enjoys the Manuscript Collective’s work.

The other draw, she says, is to spend an hour with other students who are interested in these works, along with Stallybrass and Pollack.

“It’s the materials we work with, but also the group, the vibe,” says Wen. “It’s amazing to see how we progress.”

Part of the learning is to decipher an author’s handwriting, intent, and purpose. “It is training your sensibility to different kinds of handwriting, Whitman in particular,” Wen says.

Hung says that, although he has always been interested in writing, through his work with the Manuscript Collective he has realized how much can be gleaned from the written text itself.

“We can learn the writer’s psychological state through their changes in the drafts,” he says. “In the versions of Walt Whitman’s poem that we just read, there are some minute but not insignificant changes that we can discover. We can learn a great deal about Walt Whitman, the man and his thoughts, through these manuscripts.”

As the yearlong celebration Whitman at 200 kicks off this month, the Penn Libraries’ Whitman Collection will take center stage, including the work of the Manuscript Collective to be presented at the Libraries’ Whitman symposium, organized by Penn faculty and staff.

Many of the major events and exhibitions are scheduled around Whitman’s May 31 birthday.

Two of the first Whitman at 200 events take place at Penn on Jan. 26. One is the first in a series of three workshops centered around the creation, translation, and printing of images to be held in two venues, the Kislak Center and the Common Press; the other is a workshop to create a hand-lettered and illustrated Walt Whitman verse at the Arthur Ross Gallery. A Whitman portrait from the Libraries’ collection is one of 50 works in the crowd-sourced exhibit “Citizen Salon.”

Major support for Whitman at 200: Art and Democracy has been provided by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage.

Lynne Farrington is a senior curator, special collections (Kislak Center), in the Penn Libraries and the project director for Whitman at 200.

Peter Stallybrass is the Walter H. and Leonore C. Annenberg Professor in the Humanities Emeritus, Professor of English and of Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Emeritus, and co-director, the History of Material Texts Emeritus, in the School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania.

John Pollack is curator, research services (Kislak Center), in the Penn Libraries.

Louisa Shepard

nocred

nocred

Despite the commonality of water and ice, says Penn physicist Robert Carpick, their physical properties are remarkably unique.

(Image: mustafahacalaki via Getty Images)

Organizations like Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships foster collaborations between Penn and public schools in the West Philadelphia community.

nocred