Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

More than 42 million people in the United States who identify as Latino or Hispanic have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. This statistic, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s COVID data tracker, tells one side of the story regarding Latino people, who make up about 19% of the U.S. population or 62 million Americans.

But a research team including Penn’s Adriana Perez, Elena Portacolone from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), David X. Marquez from the University of Illinois Chicago, and colleagues wanted to better understand the other side: What might deter millions of unvaccinated Latino people from getting a shot that could protect them against the coronavirus?

In a qualitative study conducted between April and June 2020—before a COVID-19 vaccine existed—the researchers learned that for Latino communities four main barriers come into play: access to appropriate health care services, money, immigration concerns, and misinformation. The team shared its findings in the journal PLOS ONE.

“We’re falling short on outreach that is culturally and linguistically relevant, that is considerate of people who aren’t just culturally diverse but who have specific needs and continue to struggle with equity and access,” says Perez, an associate professor in Penn’s School of Nursing.

Many barriers exist for Latino adults, says Marquez, a professor of kinesiology and nutrition in UIC’s College of Applied Health Sciences. “Most are rooted in inequities that Latino people face. This study brings some of those to light and how we might better address them.”

The work emerged out of a study that began in 2019 focused on factors that influence Latino participation in research. To answer questions specific to COVID-19 and vaccination, Perez and colleagues recruited individuals already involved in the overarching study who were 18 or older and who self-identified as Latino or Hispanic.

With these 21 adults, they conducted three focus groups. Participants had an opportunity to share how they felt about getting tested for COVID-19 and whether they might get inoculated once a vaccine came to market.

In addition, the researchers interviewed 12 administrators of organizations serving primarily Latino communities in urban and rural California. During these video calls, participants answered questions about barriers they saw to testing and vaccination. Finally, about a year after COVID-19 vaccines became widely available, the research team followed up with its advisory board of Latino leaders to validate and expand the findings.

Four central themes emerged from those discussions.

The first was a lack of access to high-quality health services. “Not having a place to go for care was a big concern,” Perez says. “Latinos as a group have one of the highest uninsured rates in the country, and many live in rural communities. They expressed to us that they were really pressed for resources, they were really being stretched.” Beyond that, some reported reluctance to interact with health care providers, who they often viewed as “government agents.”

When it comes to public health and COVID-19, our system doesn’t take into account a person’s culture. We’re still missing the mark for Latinos across the country.

Adriana Perez, associate professor, Penn Nursing

Similar sentiment underpinned the second theme, which centered around immigration. One focus group participant summed it up plainly: “All roads lead to possible deportation.” Portacolone, an associate professor at the Institute for Health & Aging at the UCSF School of Nursing, says such fears around immigration repercussions are ever-present. “This is the often-secret suffering of rural and urban Latino/Hispanic communities,” she says. “It was particularly prevalent at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, when vaccines weren’t yet on the horizon.”

As a third theme, the researchers noticed that participants expressed concerns over the pandemic’s financial repercussions, lost employment or income that could lead to an inability to pay for food and housing. This trickled down to the vaccination as well; people reported anxiety over the vaccine’s cost, transportation to get it, and the time and money they would potentially leave on the table should they have to miss work.

The fourth theme the researchers identified was a lack of reliable information around the COVID-19 vaccine. “The misinformation aspect was interesting,” Perez says. Participants noted getting mixed messages from traditional and social media, turning instead to trusted family members and others for information. “They would get a message on TV that’s not congruent with what they were hearing on the ground,” says Perez. “For COVID—and many other public health issues, for that matter—there needs to be clear messaging.”

Beyond consistent communication, overcoming vaccine uptake barriers within the Latino community in the U.S. will require relevant public health policy, better coordination between state and local governments, and more resources, according to the researchers. “When it comes to public health and COVID-19, our system doesn’t take into account a person’s culture,” Perez says. “We’re still missing the mark for Latinos across the country.”

And yet, there’s reason for hope, Portacolone says.

“The majority of this suffering can be addressed via an intentional and long-term commitment by policymakers, public officials, health care providers, and private entities to eradicate inequities,” she says. “This could include expanding access to health care and making paid sick and family leave mandatory, among other ideas. Overall, these findings call for a strong commitment to equity.”

Adriana Perez is an associate professor in the Department of Family and Community Health in the School of Nursing at the University of Pennsylvania and a senior fellow at Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics.

Elena Portacolone is an associate professor in the Institute for Health & Aging in the School of Nursing at the University of California, San Francisco.

David X. Marquez is a professor of kinesiology and nutrition in the College of Applied Health Sciences at the University of Illinois Chicago.

Other co-authors on the study include the University of California, San Francisco’s Julene K. Johnson, Sahru Keiser, Paula Martinez, Javier Guerrero, and Thi Tran.

Michele W. Berger

Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

nocred

nocred

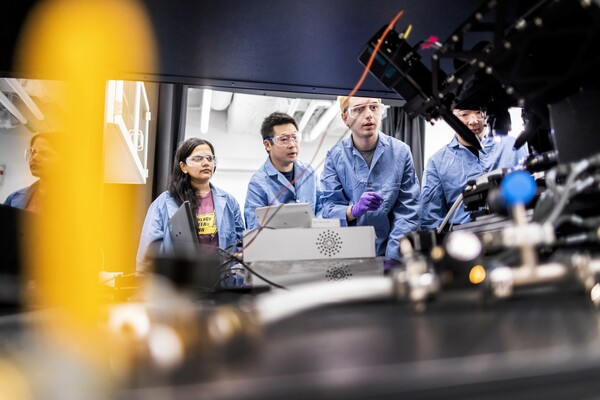

(From left) Kevin B. Mahoney, chief executive officer of the University of Pennsylvania Health System; Penn President J. Larry Jameson; Jonathan A. Epstein, dean of the Perelman School of Medicine (PSOM); and E. Michael Ostap, senior vice dean and chief scientific officer at PSOM, at the ribbon cutting at 3600 Civic Center Boulevard.

nocred