(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

The field of architecture and design has played a vital role in protecting public health during the ongoing pandemic, from offering strategies to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 to understanding how health and the built environment are connected.

The many impacts of COVID-19 were also apparent during this year’s La Biennale di Venezia (Venice Biennale), an international architectural exhibition that began this May and runs through Nov. 21, though it was originally scheduled for 2020. While this event looked quite different from previous iterations, and with its theme of “How will we live together?” taking on new significance amidst the ongoing pandemic, representatives from Penn were able to contribute to the exhibition with both virtual and physical submissions.

Faculty from the Stuart Weitzman School of Design’s Department of Architecture first became connected to the Biennale through a collaboration with Egypt’s Ministry of Heritage and Culture during a design studio on informal settlements in Cairo. The studio course, initiated by department Chair Winka Dubbeldam and led by associate professor Ferda Kolatan, culminated in an exhibition at the Egyptian Pavilion at the Biennale in 2016. Two years later, Penn returned to the Biennale with submissions from both students and faculty.

Dubbeldam explains that the 2020 Biennale exhibition was originally planned to be “way more intense” than years past, with plans for a carbon fiber pavilion with lecturers Ezio Blasetti and Danielle Willems and the output of a design-research studio focused on architecture and urban design in Istanbul with Kolatan, that then shifted because of the pandemic.

As the Biennale adapted to COVID-19, Dubbeldam was brought on to be one of the creative directors of the City X Venice Italian Virtual Pavilion, the Biennale’s first-ever virtual pavilion. “What they were looking for is how architecture interacts and engages with nature, and how nature could become instrumental in architecture,” Dubbeldam explains about the virtual pavilion. “The theme we were given was very symbiotic—not one beyond or above the other—and I found that an interesting challenge.” This exhibit will culminate in a large publication by the Venice Biennale to come out in 2022.

What they were looking for is how architecture interacts and engages with nature, and how nature could become instrumental in architecture.

Winka Dubbeldam, Miller Professor and chair of graduate architecture in the Weitzman School

As part of the output for the Italian Virtual Pavilion, Dubbeldam also brought together the Penn architects in a LOG’rithmn panel, hosted by Cynthia Davidson, for an online conversation on “The Science of Architecture,” with goal of expanding the role of architecture in society and nature. “We are only going to be of value to society if we allow ourselves to push these boundaries,” she said during the panel, which took place in July. “Architects have been passive, and we need to start to become more proactive participants. It is important to understand that there is a difference in theoretical thinking and research in architecture versus other ways of pushing boundaries in practice.”

Panelists Dorit Aviv, Laia Mogas-Soldevila, Karel Klein, Kolatan, Masoud Akbarzadeh, and Robert Stuart-Smith showed animations of their work and discussed the essential role of research in their work, how science can help architects understand and explore new approaches to their work, and what it takes to be both speculative creator and realizer. Specific topics discussed include bio- and geometric-inspired designs, thermodynamics, neural networks, and embedded aesthetics that demonstrated how one could see the science of architecture in the largest possible scope.

Dubbeldam says that the event was a “great cross-disciplinary discussion” that allowed a wide range of scholars to talk and think about what research meant across the department and how to push existing boundaries. “It was great to see that the research was appreciated by colleagues of other architecture schools, and also we thought it was important to have the discussion afterwards,” she says. “While it was disappointing that we didn’t get to build at the Biennale itself, between the Virtual Pavilion and the panel discussion it was, in a strange way, almost more interesting on a whole different level.”

In August, another exhibition featuring work by Weitzman faculty, “FEEDback – It’s About Time!,” will open in Venice. Curated by Eric Goldemberg, it is a modified version of an exhibition organized by Florida International University in 2020 that explores the role of feedback—both instrumental and conceptual—as a critical part of the design process. The exhibition includes work from Ali Rahim, professor of architecture and director of the MSD-AAD program; Hina Jamelle, senior lecturer in architecture and director of urban housing; Kolatan; and Simon Kim, associate professor of architecture.

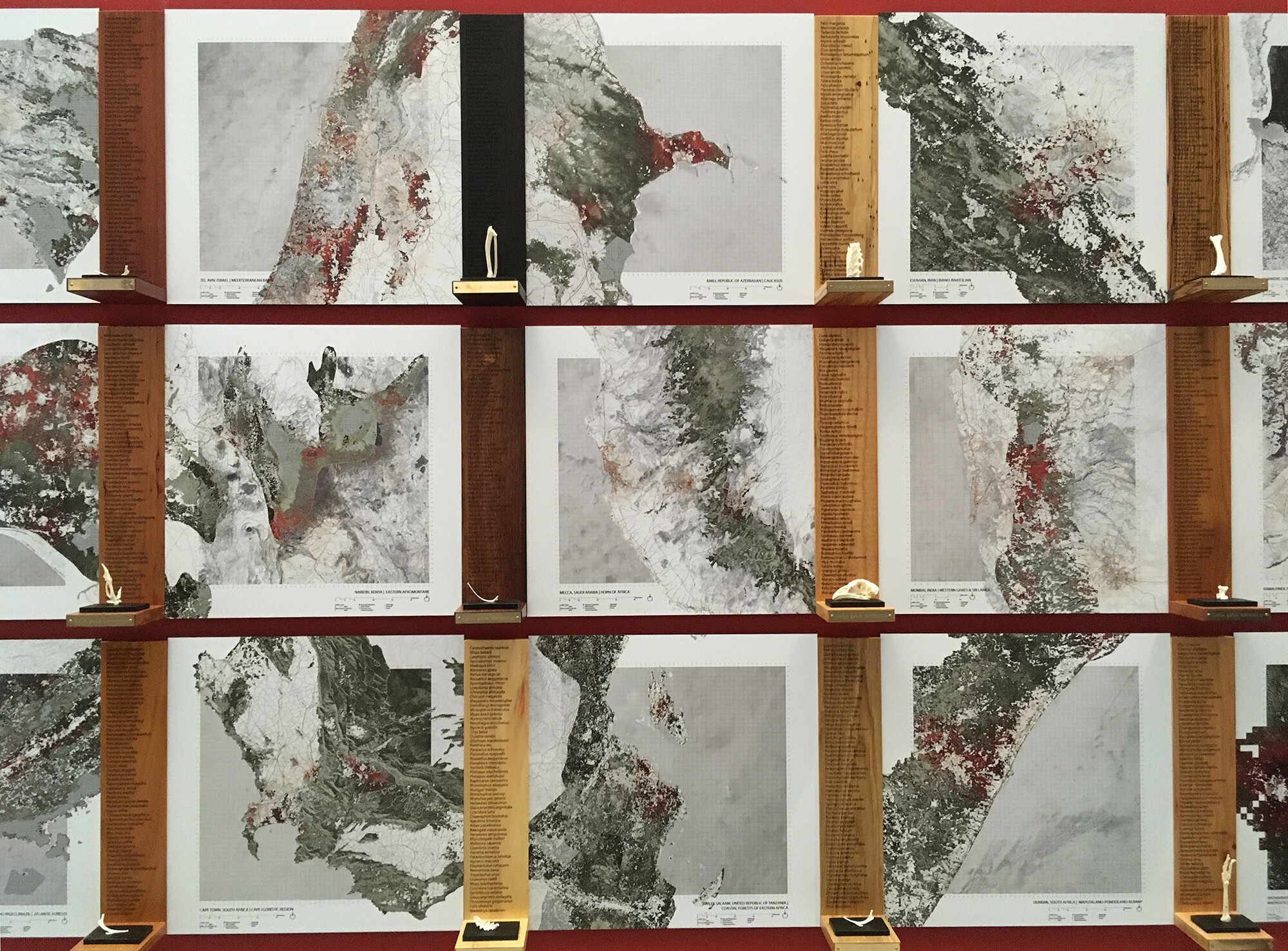

Currently on display at the Central Pavilion is an exhibit by Richard Weller, professor and chair of landscape architecture and co-executive director of The McHarg Center. “What we can’t live without” is a three-part exhibition that addresses the question “How will we live together?” from the lens of the relationship of humans and animal kind.

“The work argues directly that landscape architects, planners, and others can plan land use and urban growth in a way that’s compatible with other species rather than just always being focused on human interests,” Weller explains. “Ultimately, doing that is in our best interest, because without that biodiversity ecosystems collapse.”

This is especially important in the context of COVID-19, Weller adds. “This happened because of a breakdown in ecological health, and ultimately it goes back to how we manage landscapes,” he says. “If those species and ecosystems were healthy and intact, then this disease might not have jumped. We have to be able to think about more than just human interests.”

In “World Park,” Weller presents a proposal for a global network of restored lands, one that stretches across 55 of the world’s most biodiverse nations, and creates three hiking and nature trails that connect Namibia to Turkey, Australasia to Morocco, and Alaska to Patagonia. Its goal is to form a continuous landscape that helps species migrate and adjust to the impacts of climate change. “I want people in the broader community to start to see that it’s only as outlandish as a big, national park was in the 18th century,” Weller says.

The second installation “Hotspot Cities” focuses on 33 of the largest and fastest growing metropolitan areas and the threat they pose to endangered species and their habitats. Designed to be a call to action and to highlight the role that design can play in mitigating the threats against biodiversity, the exhibition includes maps that show forecasted growth to the year 2050 and how that growth overlaps with the remaining habitats of threatened species.

Finally, “Not the Blue Marble” is a simulation of a future Earth where only current protected areas remain, which includes around 15% of the Earth’s land mass and a small area of marine habitats. The simulation can be seen through a 3D printed replica of the Apollo 11 hatch, but instead of the surface of the moon, the observer/astronaut looks down at Earth alongside instructions on how to reinhabit its remaining fragments.

Weller says that while it can be “dangerous” for artists to have too much time, his team was able to maintain consistency and used the pandemic delays to enhance the exhibition’s construction. “It’s a risk because you might fall out of love with an idea or lose interest, which can be quite disheartening,” Weller says. “Or, it gets better because you have time to refine, and you can make things more carefully. With this, there was time for reflection, which is good.”

On display in the “Among Diverse Beings” section are three pieces by fine arts professor Ani Liu, who was invited by Biennale curator Hashim Sarkis to approach the theme at the scale of the body. Combining her interests in gender-specific design and the human body with both the personal and global shifts she experienced over the past year and a half, Liu’s installations are meant to open up conversations on how to make lives better through design.

“Pregnancy menswear” depicts a genderless pregnancy suit and shows how design can open up doorways to talking about what is culturally normative. The work also remakes previously stigmatized assumptions about the relationship between gender, fertility, and parenthood.

Following a similar theme is “AI Toys,” a series of color schemes, titles, and descriptions of toys that depict how society constructs gender roles in early childhood. The toys were created by a machine learning algorithm that was trained on real toys sold on Amazon and Target. An example “girl” toy is “Beyond Anything in the World Princess Castle Tent,” whose description includes words like “heart shapes,” “versatile looks,” and “glitter and glamour” while one of the “boy” toys, “NERF N-Strike Elite Series 30-Dart Refill,” is “inspired by the blaster used in Fortnight” and has a “fast reload, and Lightning Strike Scope extension.”

Liu’s third installation, which is also available online and in the App store, is a video game called “Shapes and Ladders: Battles of Bias & Bureaucracy.” The game, projected in the shape of a large building at the Biennale, is a first-person simulation of structural inequality and was spurred by the murder of George Floyd and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement last summer. The installation also embraces a format that was inspired by the sudden shift to more virtual interactions during the pandemic. “During the pandemic I started to notice more people were playing video games such as Animal Crossing as a form of escapism. I was interested in using the video game as a platform for art making and social change,” says Liu.

“Shapes and Ladders” has its players (depicted as either a circle, square, or triangle) navigate an office setting while attempting to find health insurance, earn enough coins to maintain life quality, and pay off debts. However, the game mechanics differ based on the shape—a circle is more likely to encounter workplace sexual assault and has access to fewer coins, for example—and players cannot choose their shape when they start the game.

While Liu has not been able to travel to Venice, she’s been able to participate in conversations about her pieces through social media and hopes that her work will provide new perspectives on gendered experiences and systemic racism and sexism. “Design can do a lot to open up these conversations and to spark real world change,” says Liu. “I hope that people will become more critical consumers of design and technology, especially in collectively imagining futures we want to live in.”

Dubbeldam says that Penn will certainly be part of the next exhibition, now scheduled for 2023. These plans include individual faculty submissions, the studio work focused on Istanbul, and the carbon fiber pavilion, along with hosting more dialogues thanks to the success of the online conversations around the virtual pavilion.

“This has been an interesting intermezzo,” says Dubbeldam. “If we look back at this year, what was the most exciting is the fact that we tightly collaborated on this, we learned from each other, and we got into the deeper insight of what every researcher and designer is working on. It was quite incredible how inspirational that was, and it was rather unexpected.”

The 17th International Architecture Exhibition runs until November 21 2021 and is curated by Hashim Sarkis. For more information, visit https://www.labiennale.org/en/architecture/2021.

Winka Dubbeldam is the Miller Professor and Chair of Graduate Architecture in the Stuart Weitzman School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania.

Ani Liu is a Professor of Practice in Fine Arts and Design in the Stuart Weitzman School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania.

Richard Weller is a professor and Chair of Landscape Architecture, the Martin and Margy Meyerson Chair of Urbanism, and the Co-Executive Director of The McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology in Penn’s Stuart Weitzman School of Design.

Weller’s fabrication team for the Venice Biennale included alums Chieh Huang, Zuzanna Drozdz, Nanxi Dong, Shannon Rafferty, Lucy Whitacre, and Lujian Zhang and students Oliver Atwood, Emily Bunker, Tone Chu, Francesca Garzilli, Rob Levinthal, and Allison Nkwocha.

Undergraduate architecture students whose work was displayed at the Venice Biennale include Elizabeth Beugg, Sarah Borders, Alexander Brown, Lindsey Chambers, Hannah Cho, Seung Jin (Irene) Choi, Lula Chou, Alice Cochrane, Nathaly De La Paz, Jake Dieber, Mary (Beth) Finley, Benjamin Finnstrom, Zuqi Fu, Roberto Galindo-Fiallos, Audrey Hioe, Eric Hoang, Dillon Horwitz, Begum Karaoglu, Melina Lawrence, Louise Lu, Yuhui (Mindy) Ma, Charlotte Matthai, Isabella Mayorga, Nana Ntiriwaa-Berkoh, Nuri (Lucy) Jung, Antonio Rinaldi, Tomoki Tashiro, Eric Wang, Xinping Yang, Yihan Yin, Jieun Yoon, Yue (Sarah) Shi, Judy Zhang, Rongxuan (Roxanne) Zhou, Leechen Zhu.

Video by Jessica Charlesworth.

Erica K. Brockmeier

(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

Jin Liu, Penn’s newest economics faculty member, specializes in international trade.

nocred

nocred

nocred