Griffin Pitt, right, works with two other student researchers to test the conductivity, total dissolved solids, salinity, and temperature of water below a sand dam in Kenya.

(Image: Courtesy of Griffin Pitt)

In a wide-ranging discussion hosted by the Center for Latin American and Latinx Studies (CLALS), three experts on Brazil—Penn historian Melissa Teixeira, CLALS Distinguished Visiting Scholar Marilene Felinto, and founder of the Guetto Institute and A Rocinha Resiste Magda Gomes—addressed the implications of Luiz Inácio Lula Da Silva’s triumph in the country’s presidential elections and what it might mean for Latin America’s largest democracy. The panel was moderated by CLALS director Tulia Falleti.

Leftist former President Lula defeated right-wing incumbent Jair Bolsonaro in the runoff elections Oct. 30, a stunning comeback for Lula and a rebuke of four years of divisive political moves by Bolsonaro, in which he targeted the media and the left, exacerbated the coronavirus pandemic that left 700,000 dead, and most recently sought to undermine the elections themselves. Bolsonaro’s defeat prompted thousands of his supporters to take to the streets, and truckers blocked hundreds of roads around the nation in protests that have since fizzled.

Felinto, a renowned columnist for the Folha de S. Paulo and award-winning author, told the audience that those protests hampered her arrival on campus last week, as she had to leave for the São Paulo airport 10 hours before her flight to wend her way around the hundreds of road blocks and protests that prevented access to the main airport and led to the cancellation of hundreds of flights.

She discussed how some political analysts in Brazil are optimistic about the defeat of the Bolsonaro project and believe it will fade away and be extinguished, one even comparing the rise and fall of Bolsonaro’s rule with the Islamic State in its rallying of religious extremists, which Felinto says are the neo-Pentecostals in Brazil.

She noted the support of President Biden, France’s Emmanuel Macron, and other international leaders immediately after the election, as well as international rejoicing and relief helped the country accept the results.

Felinto said Lula’s win was “a victory of poverty against wealth, from my point of view,” as well as the Democratic desire of a majority of Brazilians against continuing to live under fascism for another four years. The map of the election results shows it was the poorest regions of Brazil— the North, the Northeast, and the state of Minas Gerais—that gave Lula the victory.

She noted that Lula also performed well in large, progressive urban centers like São Paulo and its metropolitan region.

“Lula’s victory also means the affirmation of the desire of half of our society to have back in the country a policy of social justice, a policy of combating inequality, of repudiating racism, homophobia, misogyny, violence, and terror,” she said.

As for what implications Lula’s win will have for democracy in Brazil, Felinto pointed to political analysts who say he needs to build coalitions right away while others have fears of what might happen before Lula is officially installed in January—not just a threat of a coup but also the possibility of Lula’s assassination.

“Lula’s victory is the only chance we have to remake the country,” she said.

Gomes appeared from Rio de Janeiro via Zoom and noted the importance of having this discussion about democracy, Brazil, and elections.

“It’s not something that should worry Brazil but the world,” Gomes said.

Looking at the size of Brazil’s population, it’s important to protect democracy there, she said.

Teixeira situated Lula’s win in a longer historical arc to think about what his election means for Brazil going forward.

After the intense polarization of social and political life in Brazil as well as violence targeting marginalized communities, “I think for many in Brazil, there’s been a momentary sigh of relief with Lula’s election in terms of how he might be a conciliatory voice in Brazil right now,” she said.

She discussed the many ways his election is historic: Lula will be the first leader to serve three democratically elected terms; he saw the largest number of votes cast in Brazil’s history, with more than 60 million people voting for him versus the more than 58 million for Bolsonaro.

“While the victory was not a landslide, I do think it was decisive in terms of how it really depended on and benefited from grassroots organizations in Brazil,” she said.

She said the win built off Lula’s legacy of being at the forefront of pro-democracy movements since the 1970s.

“It’s really fitting and really quite remarkable that, again, Lula is going to be the person to guide Brazil through another moment of rebuilding democratic institutions,” she said.

Lula’s government in the past has focused on the expansion of social programs and poverty alleviation programs through state funding and during his previous term Brazil became a beacon and model of social justice, not only for other countries in Latin America but also for other countries in the Global South, Teixeira said.

The test will be to see how Lula can adapt his programs in these current, more uncertain economic conditions and amid the political opposition that he faces as Bolsonaro’s party made important gains in Congress and state government.

“There’s a lot to be optimistic about with Lula’s election,” she said. “But also, there’s some uncertainty as to what will happen in the next couple of months and next few years and to what extent Lula will be able to build upon his legacy.”

Falleti asked the participants to share their thoughts on a number of topics, including what type of coalition will be necessary to get the administration off on the right foot and to give their assessment of the current situation of democracy in Brazil and prognosis for the near future.

She asked Gomes to describe the climate in her favela, the Brazilian term for a dense urban working class neighborhood, before the election and after both rounds of voting. Gomes noted that 70% of people in her community cast ballots for Lula, which was a sign of how important they felt the election was and that they saw the Lula government as one who would focus on the issues that matter to them, like anti-racism and poverty reduction.

“There were fireworks on Sunday. It looked like it was a football game,” she said, noting she roots for the Vasco team, but it looked like the Rio team Flamengo had won. “It was a party. Everybody was jumping around. It was a huge celebration. This is a government of hope and celebration.”

Kristen de Groot

Griffin Pitt, right, works with two other student researchers to test the conductivity, total dissolved solids, salinity, and temperature of water below a sand dam in Kenya.

(Image: Courtesy of Griffin Pitt)

Image: Andriy Onufriyenko via Getty Images

nocred

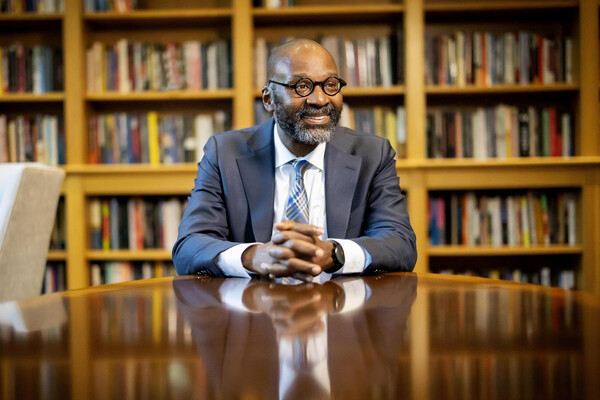

Provost John L. Jackson Jr.

nocred