nocred

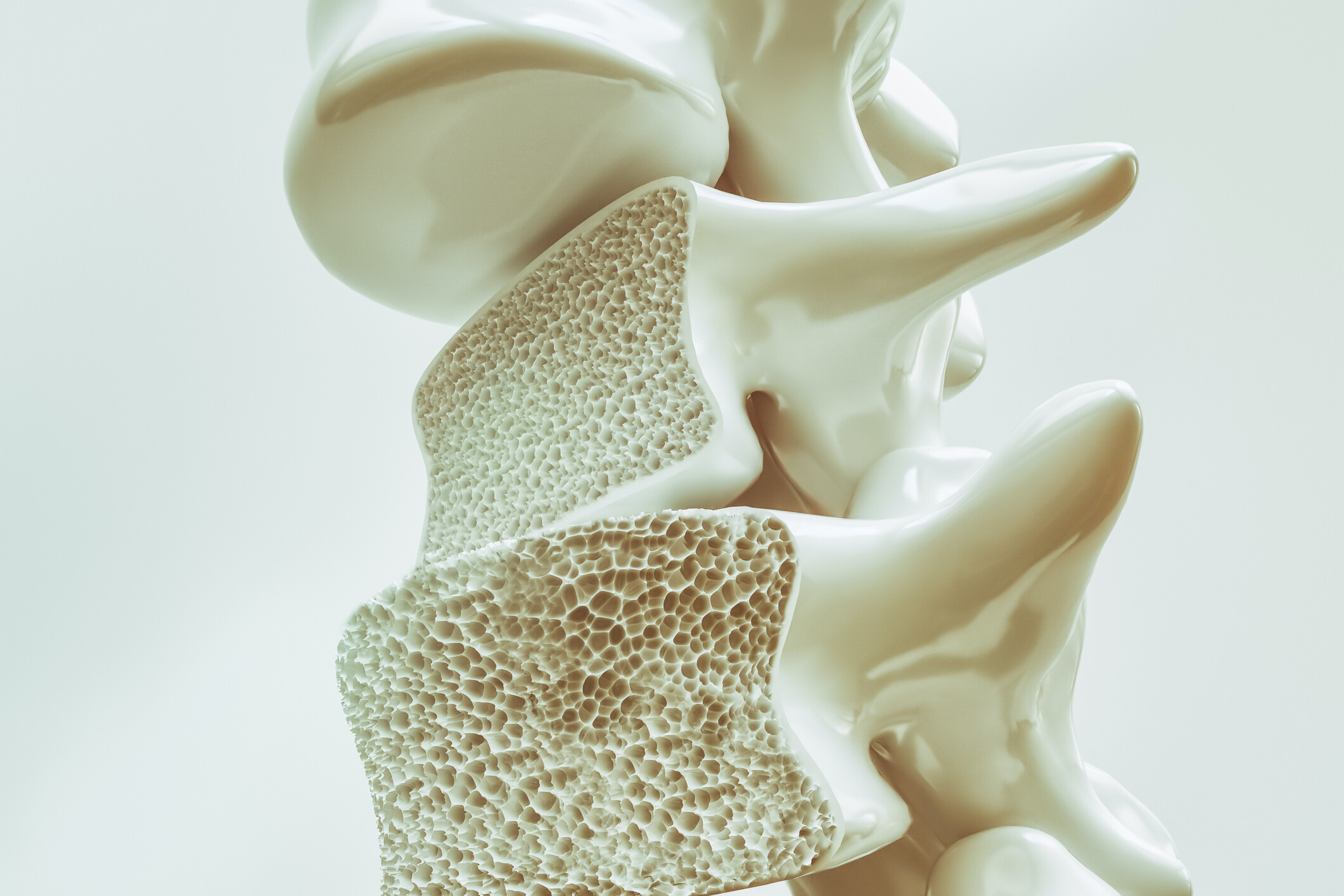

Bone remodeling in the body involves a balancing act between osteoblasts, cells that build bone, and osteoclasts, cells that break it down. Diseases such as osteoporosis, arthritis, and periodontitis involve bone loss, and are linked with an overabundance of osteoclast activity.

In a new paper published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and colleagues offer new insights into the regulation of osteoclasts, potentially shedding light on the imbalances that can cause disease. The work identifies the protein IFT80 as a key player in keeping populations of osteoclasts in check. The team found that mice lacking IFT80 grew larger-than-expected populations of osteoclasts, and subsequently developed severe osteopenia.

“When you think about translation to the clinic, we believe this finding is very important,” says Shuying (Sheri) Yang, an associate professor in Penn’s School of Dental Medicine and the study’s senior author. “As we begin to understand the mechanism and the gene function of IFT80, we may be able to consider it as a potential therapeutic target. For example, a DNA- or mRNA-based therapy that introduced this protein could help treat certain bone diseases.”

Yang and colleagues became interested in IFT80 after an earlier study in Nature Cell Biology. It revealed that IFT, or intraflagellar proteins, play a role in T cell protein transport. These proteins are a focus of Yang’s lab and the finding piqued her interest as T cells and osteoclasts are both derived from hematopoietic stem cells, the precursors of blood cells. IFTs help construct cilia, antenna-like sensory organs that extend from cells, by transporting proteins from the cilia’s base to their tip and back again. In previous work, Yang and others had shown that IFTs play critical roles in regulating osteoblasts and chondrocytes, cells that maintain cartilage, from mesenchymal stem cells, which make and maintain bone, cartilage, and other tissue types.

To explore the role of IFT80 specifically in osteoclasts, Yang’s group developed a knockout mouse line that lacked the protein in precursors of osteoclasts. Notably, they found these animals had significantly lower bone volume compared to normal mice, and their osteoclasts nearly doubled in number. “It was a dramatic change,” Yang says.

The researchers found that IFT80 prevents osteoclast precursors from giving rise to the bone resorbing cells and inhibits osteoclast maturation.

Further experimentation indicated that IFT80 interacted with a protein called Cbl-b in the protein degradation pathway regulated by the small regulatory protein ubiquitin in osteoclasts. Yang’s team found that IFT80 prevents the breakdown of Cbl-b, and Cbl-b normally degrades another protein called TRAF6. TRAF6 normally promotes osteoclast production, so by degrading TRAF6, IFT80 inhibits osteoclast differentiation.

Downstream of TRAF6, the research team also found evidence that IFT80 suppresses a signaling pathway governed by the proteins RANKL and RANK.

To test the idea of IFT80 being a potential target for intervention in bone loss disorders, the researchers overexpressed IFT80 in a mouse model that normally experiences overactive osteoclasts-caused bone loss. Doing so effectively tamped down RANK/RANKL activation, lowered osteoclast production, and increased bone volume in the mice.

The study is the first to link IFT80 with a role in osteoclasts and to find that IFT80 controls a protein degradation pathway and serves as a negative regulator during osteoclast differentiation. These features makes it a valuable target for potential therapeutic intervention, says Yang.

“Right now there is a lot of interest in how the body promotes osteoclast differentiation,” she says. “With so many diseases related to excess bone loss—osteoporosis, periodontitis, rheumatoid arthritis, even fractures—there is a big need to find ways to address bone loss and restore balance in bone remodeling.”

Shuying (Sheri) Yang is an associate professor in the Department of Basic & Translational Sciences in the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine.

Yang coauthored the study with Penn Dental Medicine’s Vishwa Deepak, Shu-ting Yang, Ziqing Li, and Xinhua Li; State University of New York at Buffalo’s Andrew Ng and Ding Xu; Tulane University’s Yi-Ping Li; and the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine’s Merry Jo Oursler.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants DE023105, AR066101, and AG048388).

Katherine Unger Baillie

nocred

nocred

Despite the commonality of water and ice, says Penn physicist Robert Carpick, their physical properties are remarkably unique.

(Image: mustafahacalaki via Getty Images)

Organizations like Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships foster collaborations between Penn and public schools in the West Philadelphia community.

nocred