(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

The history of religion in America is often told as a story of Pilgrims and Puritans, but has in fact been more multifaceted than that, says Reyhan Durmaz, assistant professor of religious studies. Various denominations of Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Native American religions, Buddhism and other East Asian religions, as well as new religious movements, have created a diverse, multivocal religious landscape in America, she says.

In Orthodox America, an SNF Paideia course offered this fall, Durmaz and her students surveyed the history of Orthodox Christian communities in North America from the early 19th century to the present. These groups immigrated from the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Russia, North Africa, and elsewhere, influencing the religious, political, legal, and literary landscapes in their new home, America.

“There is a long history of Orthodox Christians shaping the U.S.,” she says. “Russian, Greek, Syrian, Coptic, Armenian, and almost all other expressions of Orthodox Christianity were here. But we rarely hear about their stories in conventional narratives of religion in America.”

Durmaz, who is assistant professor of religious studies in the School of Arts & Sciences, began the course by looking at race and religion. “If we want to understand the history of religion in America, we have to look at the history of race and race-making,” she says, noting, for example, that in the 19th century, Italian and Irish Catholic immigrants were not considered white.

Immigrants, Durmaz says, had to navigate the racial categories and the changing ways in which the American legal system defined whiteness, which deeply shaped the experience of Orthodox Christians, like other religious minorities. “Orthodox Christians from various ethnic, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds were seen as non-white from the gaze of the state,” she says. “So, soon after these groups came to the U.S., they had to engage the legal and racial discourse to obtain citizenship. They used biological, religious, and cultural arguments to ‘prove’ their whiteness and fitness for American citizenship. Some, in the process, for example, said, ‘We are Christians and therefore white.’”

This nuances the American religious history, Durmaz says, for it shows how race was continually made and rearticulated in an increasingly more diverse society. Religious diversity in America is always filtered through racial discourse. “Those two are impossible to detangle,” she says. In Orthodox America, Durmaz and her students explored the ways Orthodox Christians participated in those conversations.

Even though the course’s main aim is to incorporate Orthodox Christianity into the main narrative of American religion, for Durmaz it’s important to highlight the diversity within the Orthodox community. This diversity, she says, is often overlooked, and Orthodox Christians have often been stereotyped in America as “easterners,” their religion being perceived as an “exotic” form of Christianity. “But, if we look closely, we’ll see that Orthodox voices in America are diverse, since Orthodox Christians immigrated to America from different backgrounds, from different places in Asia, Africa, and Europe, at different times and under different circumstances,” Durmaz says, “They have been interested in different things with regard to preserving their religion and culture, and they expressed themselves in a variety of ways in their specific local contexts. So, they have contributed to American demography, and by implication American democracy, in foundational and complex ways. So, one of the goals of the course is to use the diversity within Orthodox Christianity as a tool to destabilize the totalizing understandings of the grand categories of Protestant, Orthodox, and Catholic Christians.”

To achieve this goal of questioning the perceived homogeneity within religious categories, Durmaz employs a variety of methods including primary source analysis, guest speakers from neighboring scholarly disciplines, field trips, and archival work. Her class visited the St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church in New York City’s Ground Zero, and the students discussed the ways this church’s sacred iconography incorporates images of the World Trade Center.

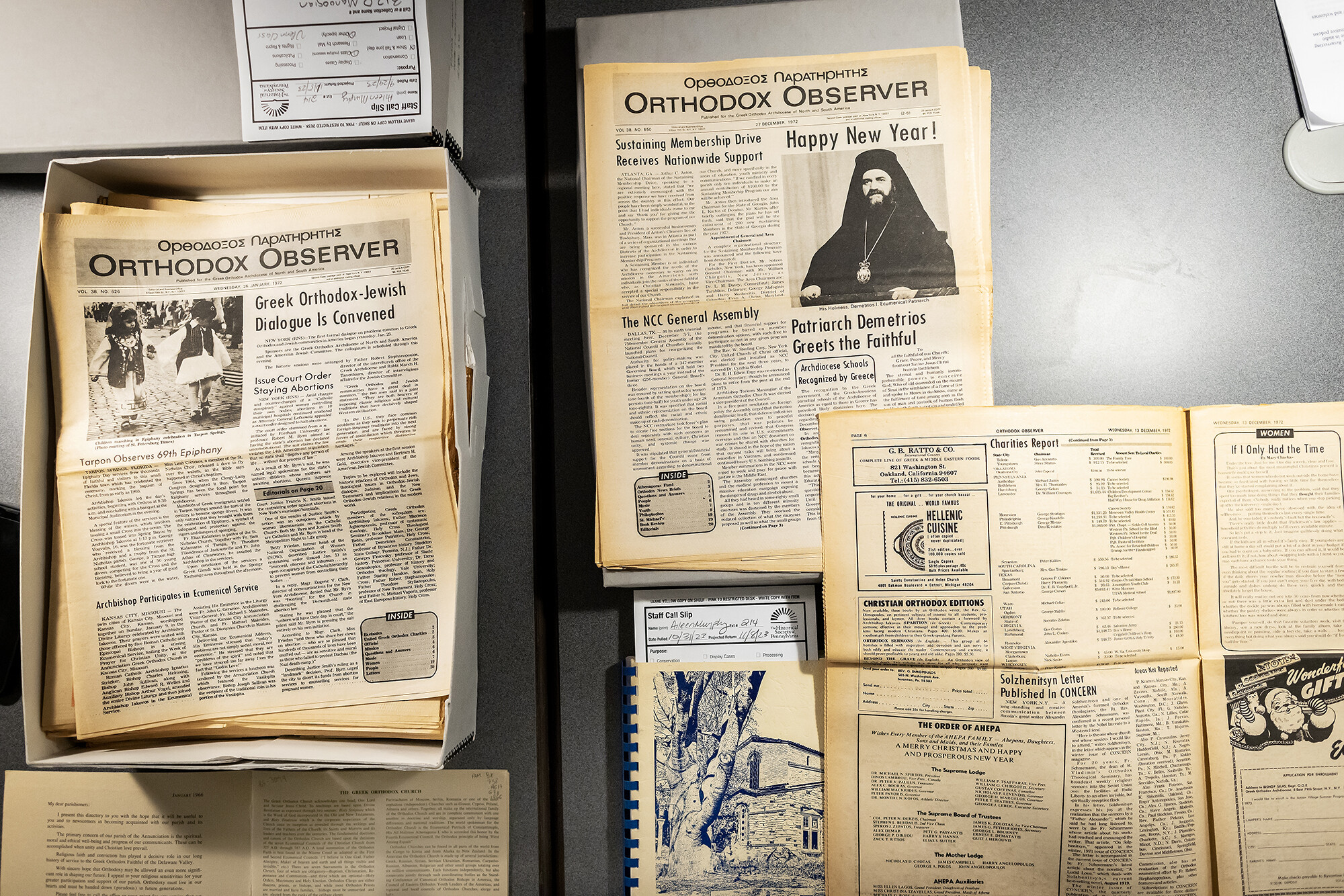

The class also visited the Historical Society of Pennsylvania to view building sketches, photographs, newspapers, and church records of early Philadelphia, its river banks and row homes populated, depopulated, and repopulated with Americans of all stripes. The purpose of this research is not only to learn about archival work but to think about the historical implications of immigrant communities who thrived in the U.S. by finding creative ways to protect and communicate their religious or cultural identities, Durmaz says.

Joseph Wilbur, a fourth-year student from Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, majoring in classical studies and religious studies, researched the names behind a parish directory at the Historical Society, finding that the priest who compiled the directory went on to publish books and that the parish itself decamped to Elkins Park, where they built a new church.

For his final project, he wrote about how Orthodox Christians talk about the 13th-century theologian Thomas Aquinas on 21st-century social media, reinterpreting the medieval Dominican priest to make sense of their current American realities.

For Wilbur, the class was an opportunity to explore his long-standing interest in Aquinas. “I could just keep reading him for the rest of his life,” he says. From political philosophy to the nature of God, Aquinas “covered everything,” Wilbur says.

Sam Herrmann, a doctoral student in religious studies, researched how 20th- and 21st-century evangelical Christians engaged with Orthodox Christianity.

In the 1990s, there was a big push from evangelicals to focus more on persecuted Christians, Herrmann says. They advocated for the International Religious Freedom Act of 1998, which declared that it was U.S. policy to condemn violations of religious freedom and channeled U.S. funds away from countries found in violation of religious freedom.

Hermann says Orthodox Christians often could not be found on these religious freedom committees. “I’m finding that evangelicals oftentimes would neglect the distinctness of orthodoxy when talking about these Christians,” he says. “There was an erasure of identity going on, mostly saying that Orthodox Christians needed to be protected without including them.”

For evangelicals at the time, “their political project was borne from the idea that they were persecuted, that modern secularity was pushing them out,” Hermann says. “It was a way for evangelicals to identify with persecution; the way they had to do that was to look globally,” and incorporate the stories of “other Christians” into their narrative of global Christian persecution.

Durmaz says she appreciates the way her students connected the history of Orthodox Christians with contemporary American life. “Although this is a history course,” she says, “I would like my students to leave the course being more aware of ongoing debates about religious freedom, American democracy, and how these debates are changing as we speak.”

Kristina Linnea García

(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

Jin Liu, Penn’s newest economics faculty member, specializes in international trade.

nocred

nocred

nocred