(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

The everyday visitor to an art museum may not know how many seconds or minutes they spent looking at a given painting or whether they spent more time with purple art or green art. But by placing participants in a virtual art gallery and using an open-source tool, researchers from the Humanities and Human Flourishing Project at the Positive Psychology Center have been able to track this kind of data and match behavior with questionnaire responses.

Studying virtual art galleries and their wellbeing benefits is a relatively new line of inquiry for the Project, a National Endowment for the Arts Research Lab. Some digital art experiences take the form of an online picture catalog of artwork while others “are almost like Google Maps Street View, where you can click through,” says Katherine Cotter, associate director of research.

Cotter and James Pawelski, principal investigator and founding director of the Humanities and Human Flourishing Project, talked with Penn Today about their research into digital art engagement.

Pawelski: This is a case of necessity being the mother of invention. When we brought Katherine on as a part of the Humanities and Human Flourishing Project, we had great plans and support to conduct research in the Philadelphia Museum of Art to see how visits there affected the visitor’s wellbeing. Unfortunately, the pandemic had other ideas.

A lot of art museums pivoted very quickly to making their exhibitions available online. Katherine had a colleague who had a very creative and dedicated partner who offered to create a virtual platform for study during the pandemic. He followed through and OGAR—the Open Gallery for Arts Research—was born. We then helped to co-develop it to add more functions.

Because of these various projects that museums had undergone—putting their art online, making it accessible virtually—these opportunities were not going to go away when the pandemic was over. Instead, they realized this is a very powerful way of engaging audiences who can’t come, or can’t come today, to the art museum. We’ve been in conversations with a variety of art museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and their digital folks there, and thinking, “How can we continue to use this platform to study the wellbeing effects of engaging with art?”

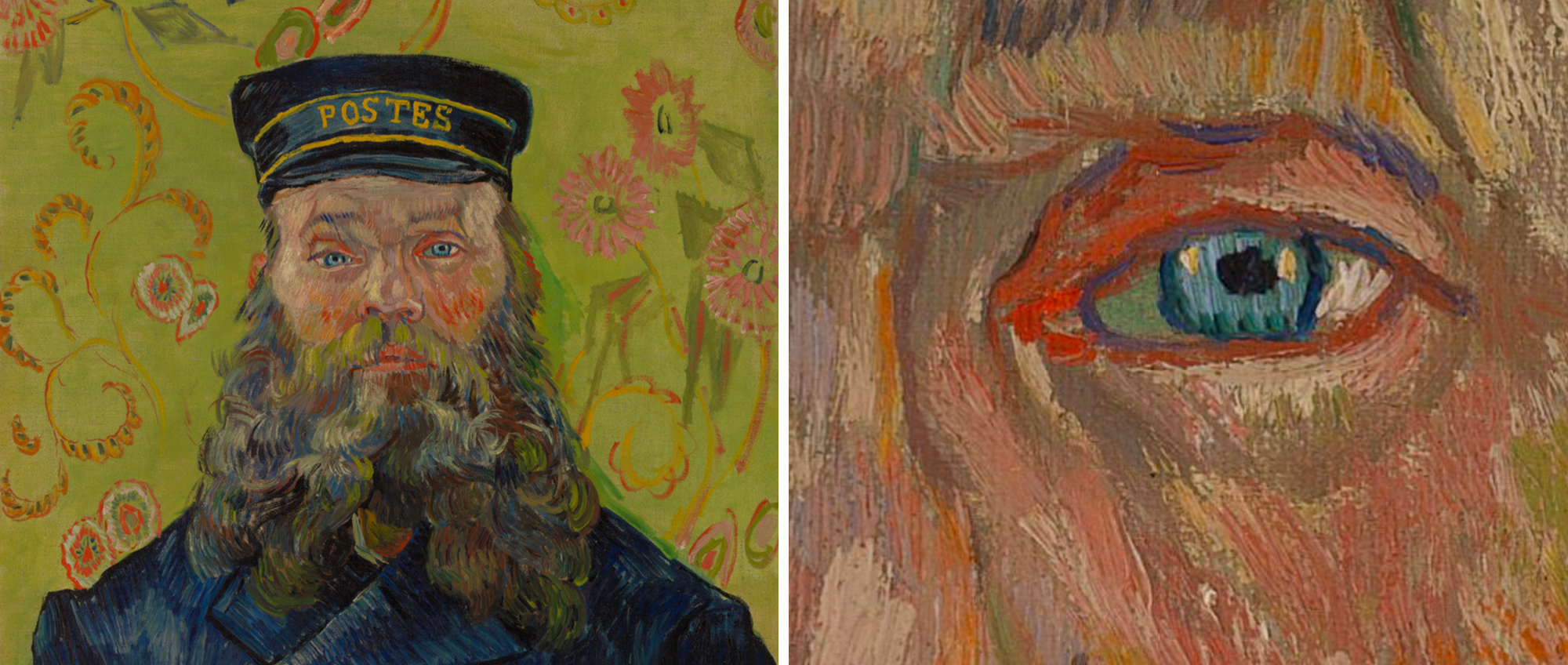

Cotter: One that I think is also really cool is Google Arts & Culture because they have such high-resolution images. You can scroll in so close to see the brushstrokes. James and I also taught a course for the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia around this topic of visual art and flourishing on their online platform, which also has some of these really nice zoom-in features. They’re doing a lot of robust online teaching and programming on a variety of topics.

Pawelski: The Humanities and Human Flourishing Project is interested in looking at connections between arts and culture and various positive outcomes. These can range from physiological outcomes—Does it have an effect on your cortisol levels? Does it have an effect on your heart rate?—to neuroscientific effects. What happens in our brains as we walk into an art museum or as we go onto OGAR?

We have a very broad notion of what we mean by these flourishing outcomes, and we have five different key pathways that we’ve identified. The first one is immersion; it’s hard to be changed by an experience in the arts and humanities if you’re not paying attention to it. The others include being able to express your feelings and your thoughts, acquiring long-term skills that you can put to use elsewhere, connecting with others, and reflecting on what the experience means to you.

Cotter: This was a gallery put together with OGAR where we partnered with the Philadelphia Museum of Art to utilize their collection and create a set of galleries featuring 30 artworks. Part of what we were interested in was what happens in the virtual gallery but also what happens when people have repeated engagement. We had people complete a series of four gallery visits, and each gallery was different, so they were seeing new art each time.

We see that people—across time—are having changes in their positive emotions, their negative emotions, and what we call aesthetic emotions, so feeling moved or in awe, or getting goosebumps or chills. But what seems to be particularly important is their immersion levels. People who are more immersed in these experiences overall have greater positive emotion, lower negative emotion, and more of these aesthetic feelings.

All five personality traits—openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—were uniquely linked to immersion, so people who are higher in these traits are reporting greater immersion. An interesting lack of effect was that none of these things was associated with people’s interest in art coming in, so it didn’t mean you had to be highly engaged with art or highly interested in art to see these benefits.

Pawelski: Another aspect of our work that I think is really valuable is that if you go to an art museum and you ask these questions, that’s great, but you have to keep in mind that you have a biased sample. These are people who have decided, for whatever reason, that this is the way they’re going to spend their day. What is it about those people versus the other people driving by who have not decided to do that? Can you really generalize from that self-selected population to everyone? But with the work that we’re doing with OGAR, these are people who are representatively selected.

Cotter: There are unique affordances to the digital. I can go to three different international museums in the same day if I want to and not have to spend all that money on airfare to get to them.

I got a not-infrequent number of responses from people doing this study saying they haven’t been to a museum in a long time because of physical or geographic accessibility, and they’re like, “It was so nice to view art again because I couldn’t.” I think there’s also some of these broader accessibility factors that come into play. If you want to go to a museum, they’re open at certain times; the internet’s always open. There’s mobility considerations as well; there’s not always a lot of spots to sit in the galleries, or they’re often taken.

Pawelski: I think in some ways, our attitudes about art need to catch up with our attitudes about music. I don’t think anybody would say, “You’re listening to Spotify? Why would you do that? That’s kind of nuts. You’re not actually with the musician? You’re not actually at the concert?”

We have incredible richness available to us in music. Why not take advantage of a similar kind of richness that we have available to us in art?

(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

Jin Liu, Penn’s newest economics faculty member, specializes in international trade.

nocred

nocred

nocred