(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

The history of Philadelphia’s water lies mostly underground, buried and dormant. Watershed maps show a slow and persistent erasure of the streams that once covered the city, branching capillaries that stretched from Chestnut Hill to South Philadelphia. With 73% of the city’s waterways piped, visible water now exists mostly in large bodies: the Delaware River, the Schuylkill River, and the Wissahickon Creek.

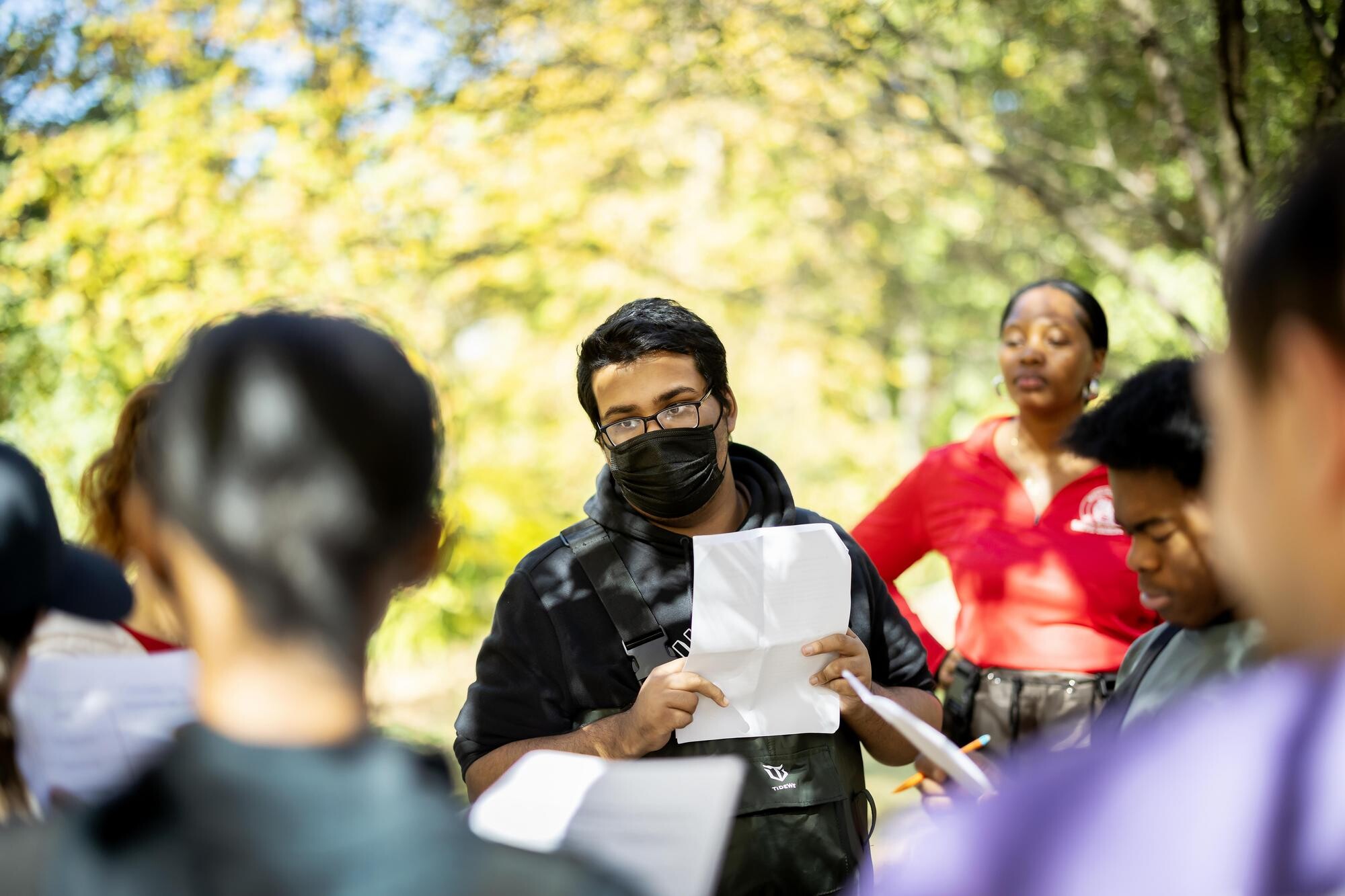

In West Philadelphia, an uncovered stream remains: Cobbs Creek, where 11 Penn students and 14 high school students from William L. Sayre High School gather on a mild morning for Rivers in a Changing World, an Academically Based Community Service (ABCS) class coordinated by the Netter Center for Community Partnerships. It is taught by Douglas J. Jerolmack, of the School of Arts & Sciences and the School of Engineering and Applied Science, in collaboration with LaRon Smith, a ninth-grade science teacher at Sayre.

This moment was two years in the making. The course grew out of a 2021 Projects for Progress award led by Ocek Eke of Penn Engineering to promote equitable access to STEM education for West Philadelphia students. Rivers in a Changing World uses environmental science and engineering to address climate change and encourage students to play an active role in their environment.

The Penn students learn alongside their high school counterparts, Jerolmack says. They lead small groups, teaching as they go. “That model, where students are co-learning and mentoring at the same time, is one of the really special parts about this course,” says Jerolmack, who is a professor of earth and environmental science and mechanical engineering and applied mechanics. “These students are stepping into a position of real responsibility.”

The Sayre students meet in 90-minute blocks, two to three times each week, depending on the schedule, says Sumaiyyah Fitchett-Fleming, one of the ninth graders. Every Wednesday, the group meets at Cobbs Creek Community Environmental Center, a West Philadelphia nonprofit with 850 acres of woods, creeks, meadows, and trails. This is what Fitchett-Fleming likes, she says, “being able to come here and learning about scientific things: what reduces erosion and what doesn’t, what affects the fish population.”

On a mild autumn day, the Penn students are tasked with leading a scientific scavenger hunt for the Sayre students, looking for signs of human modification to the creek environment. Are the banks eroded? Metal pipes rising from the stream bed? And what about trash? After a quick lesson in the Center, the students suit up in waders and head across the bridge (sign of human impact, check) and into the creek.

It looks bucolic: leaves of gold drift down to the water’s surface; the water is calm and cool to the touch. But even this landscape is not untouched.

Humans have settled around rivers more than any other natural feature, Jerolmack says. Over the centuries, rivers have been a vital source of water, food, recreation, and transportation. “There have been humans modifying this creek for a long time,” Jerolmack says, whether with 18th-century mills built to grind flour or modern green stormwater infrastructure.

For 200 years, cities have been trying to keep water out of the streets, he says. “What we’ve done is built a super-efficient system for taking a lot of water and funneling it to streams. During periods of high flow, that’s a problem. Now when you look at what the urban streams receive, it’s huge.”

Jerolmack points to the sediment at the creek bottom. The largest rocks mark river velocity at its highest, he says, and heavy objects are barely able to move when the river is flooded. Rivers adjust to floods, he says, and these days, in a time of accelerated climate change, floods are becoming larger and more frequent.

“Rivers have always had the capability to flood, but with increased flooding and the consequences of industrialization and pollution, we now recognize that in super-dense areas, this resource has also become a hazard to us,” Jerolmack says.

The river, in essence, is an indicator of how we treat our environment. If you want to get a diagnosis of the health of our landscape, go to the river. That’s where everything ends up.

Douglas Jerolmack, Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Endowed Term Professor of Earth and Environmental Science

In Philadelphia, rivers have widened, banks have been cut, and infrastructure built around waterways has been undermined by increased water volume, he says. In Cobbs Creek, pipes that were once built five to six feet below the stream bed are now visible.

As dated engineering fails, there is enough information to show why. “America has a lot of problems,” Jerolmack says. “One thing to be proud of is the density of our stream gages.”

Scientists are now gathering enough data to show that water flow is changing dramatically. The famous “hockey stick” graph showing mean temperature change over time is mirrored by hydrographs showing increasing river levels. The quantity and quality of the waterways has changed, with fewer fish and macroinvertebrates present as erosion volume increases, Jerolmack says. “The river, in essence, is an indicator of how we treat our environment,” he says. “If you want to get a diagnosis of the health of our landscape, go to the river. That’s where everything ends up.”

To the students, Jerolmack asks, “Can you see any effects on Cobbs Creek that indicate that it gets any more discharge than it used to?”

Fitchett-Fleming works in a group with classmate Rayazul Arnob, who is somewhat infamous for picking up a crayfish to show to the group. “I picked him up on his back so he could not pinch me,” says Arnob, whose favorite part of the class is getting into the water and finding animals and insects.

Fitchett-Fleming and Arnob quickly identify erosion. “The dirt’s getting carried away by the water,” Arnob notes. “Chunks of wall all over the stream bank.” To reduce erosion, humans have built walls and planted trees, he says. “We saw a bunch of those spots.”

Cobbs Creek is about one mile from Sayre High School, says Smith, who teaches the ninth-grade science course. But for many students, it’s their first time getting their feet wet.

“It’s amazing for me to see this,” Smith says. “Let the students see nature and ecology outside of the neighborhood. See how nature actually works.”

Smith is a former landscape gardener from South Philadelphia who switched careers after a shooting on his nephew’s block in 2002. Smith saw different pathways for young people in Philadelphia, saw how one wrong turn can lead to another. He wanted to put himself in the position to mentor a younger generation. “I have love for the kids and their future,” Smith says. “I think my passion is for them to be better individuals, better human beings.”

Vicky Zolotar, a third-year Penn student from Needham, Massachusetts, majoring in materials science and engineering, is interested in creating sustainable materials and wanted to think about the environmental impact of engineering. But the best part of this class isn’t the environmental component, she says. It’s meeting with Sayre students.

With an ABCS course, “you’re partnering with the Netter Center; you’re working in the West Philly community. And that’s just something I've always loved,” says Zolotar, who has volunteered with the West Philadelphia Tutoring Project, an outreach program of Penn’s Civic House.

Teaching is a way of learning, says Cypress Kaulbach, a third-year Penn earth science major from Philadelphia. She took a course on freshwater ecology last semester and enjoyed the material but says she wanted to get out into the environment to better comprehend the information.

“That experience of getting in the creek and putting the waders on, it’s super exciting for the students and it’s super exciting for us,” Kaulbach says. “The creek shapes our relationships.”

Kaulbach has spent a lot of time on the Schuylkill River, first as a high school student and later as a member of the Penn Women’s Rowing team. “I think a lot about rivers and I have always been very close to the environment,” she says.

Jerolmack wants students to understand how the environment has been negatively affected by human activity, but he also wants the environment to positively influence the students. “Creeks like this are still an oasis in an urban landscape,” he says. “This is still a ribbon of green in an otherwise super-developed place.”

Cobbs Creek is a place of solace, he says. “We can go here and we can learn about our influence on the environment, but we can also come and just enjoy this place.”

That’s the balance Jerolmack wants to hold with this class, he says. “The other thing is, I just love rivers.”

Douglas Jerolmack is the Edmund J. and Louise W. Kahn Endowed Term Professor of Earth and Environmental Science in the School of Arts & Sciences and professor of mechanical engineering and applied mechanics at the School of Engineering and Applied Science.

One of 41 ABCS classes coordinated by the Netter Center for Community Partnerships this semester, Rivers in a Changing World was co-developed by Ocek Eke, director of Graduate Students Programming at the Pen Engineering, and Jerolmack, along with Zachary Steele of the Netter Center and Jazmin Ricks of The Water Center.

Jared Rusnak, a Masters of Environmental Studies student who participated in the Netter Center’s Penn Graduate Community-Engaged Research Mentorship program last summer, is the teaching assistant for the course and helped to develop the labs central to this semester’s curriculum.

William L. Sayre High School is a University-Assisted Community School supported by the Netter Center.

Kristina Linnea García

(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

Jin Liu, Penn’s newest economics faculty member, specializes in international trade.

nocred

nocred

nocred