(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

4 min. read

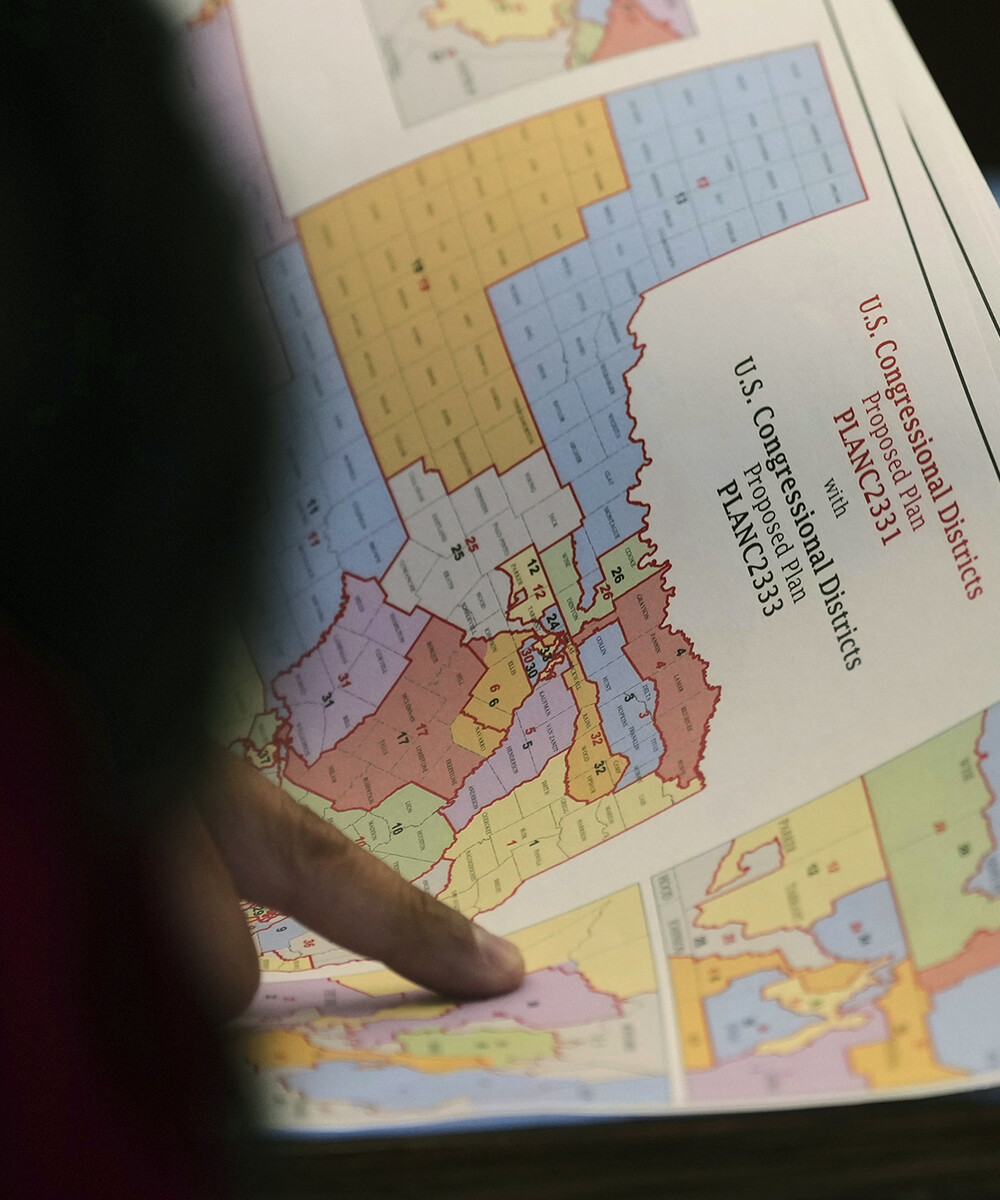

Image: Eric Gay via AP Images

Recent votes in Texas and California seeking to reshape congressional districts and thus possibly control Congress have sparked new conversations about gerrymandering.

Penn Today spoke with Matthew Levendusky, professor of political science in the School of Arts & Sciences (SAS) and the Stephen and Mary Baran Chair in the Institutions of Democracy at the Annenberg Public Policy Center, and Philip Gressman, professor of mathematics in SAS, to learn more about gerrymandering. Levendusky’s research focuses on how institutions influence political behavior, and Gressman was part of a team of mathematicians that submitted a district map for consideration during Pennsylvania’s most recent redistricting efforts.

Gerrymandering arises when mapmakers want their party to control as many districts as possible and draw district lines to get what they want. Levendusky and Gressman shared the history of the practice, how gerrymandering is done, its legality, and how technology has changed the redistricting process.

Matthew Levendusky: Every 10 years after the federal Census, states must redraw their congressional district boundaries to reflect any changes in population. In that process, state legislatures sometimes draw districts to favor one part or the other or, in some cases, to favor incumbents of both parties. People typically call these sorts of districts ‘gerrymandered.’ A strict definition is difficult, but typically it centers on manipulating the district boundaries to achieve some end, typically favoring one political party.

It is important to note that just because a district heavily favors one party or the other does not mean that it was gerrymandered. For example, in the congressional districts containing most of Philadelphia, PA-2 and PA-3, the Democratic candidate wins easily. That’s not because of gerrymandering but rather because the city is overwhelmingly Democratic. Likewise, if you went to congressional districts PA-15 or PA-13 in the middle of the state, the Republican wins handily because the voters there are largely Republican.

Levendusky: It comes from Elbridge Gerry, one of the founding fathers who later served as Massachusetts governor and U.S. vice president. He asked the Massachusetts legislature to redraw districts to favor his party. A cartoonist claimed the map resembled a salamander, hence the name.

Levendusky: There are two main types: racial gerrymanders and partisan ones. Because race and party are strongly related to one another, it is hard to differentiate the two, but the distinction matters legally. The Supreme Court ruled that it cannot intervene in partisan gerrymandering cases (Rucho v. Common Cause), but it can and does intervene in racial gerrymanders. But while the Court ruled federal courts cannot intervene in partisan redistricting, state courts can; that is how Pennsylvania was redistricted, for example.

Typically, in a partisan redistricting, those drawing the map try to either concentrate voters from the other party into overwhelmingly lopsided districts, called ‘packing,’ or they’re spread out over multiple districts but in numbers such that they are unlikely to win. That is called ‘cracking.’ The idea is to give your side enough voters in each district so that they’re likely to win, while also maximizing the number of seats your side wins.

Philip Gressman: When districts are gerrymandered, the distribution of representatives is distorted in ways that do not match the distribution of voters. In cases where there are two main parties which are very similar in size, it’s possible in some cases for gerrymandered maps to confer substantial unearned advantages to the party drawing the map.

Gressman: Gerrymandering laws differ among the states. Pennsylvania law recognizes certain ‘neutral criteria’ which require districts to be compact, to be contiguous, to have equal population, and to minimize the division of political subdivisions, e.g., to divide existing voting districts only when necessary.

These neutral criteria make gerrymandering more difficult but not impossible. The Voting Rights Act also places important limits on gerrymandering but does not end the practice. A major issue, though, is that, unless it is done in a very extreme or public way, it might be difficult to say conclusively whether a specific map is gerrymandered or not.

Gressman: Over the last 10-15 years, computing power has grown to the point that it’s now possible to use computers to generate fair district maps and, perhaps more importantly, conduct impartial testing to help identify and push back against partisan gerrymandering. Suppose, for example, that a state legislature redistricts in such a way that the majority party gains four new seats. It’s not necessarily obvious just by looking at a map that partisan interests have put a thumb on the scale. Maybe, for example, the number of voters in the majority party has grown since the last map was drawn.

What computers can do is provide an important frame of reference. A computer can be programmed to generate tens or hundreds of millions of valid maps essentially at random, all satisfying the necessary legal requirements. The algorithm used by the computer can be scrutinized to ensure that it isn’t explicitly favoring one party over another. If it’s extremely difficult for an unbiased algorithm to reproduce the same outcome, gaining four seats for the majority—i.e., if only a very small fraction of the millions of maps in the ensemble had similar results—that’s a strong indication that the legislature’s map is not reasonable or fair.

(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

Jin Liu, Penn’s newest economics faculty member, specializes in international trade.

nocred

nocred

nocred