(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

Children in the U.S. are often introduced to America’s troubled and cruel history through movies, television programs, and children’s books. Historical fiction is frequently the means by which children learn about atrocities such as the enslavement of African Americans, racial segregation, Japanese-American internment, and the genocide of Native Americans.

Discourse about these topics in children’s literature can be difficult in light of the books’ overall function to inspire, transmit values, and spark young minds. But an omission or inaccurate portrayal of the crimes and suffering can do lasting societal damage to readers and how they see the world.

Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, an assistant professor in the Graduate School of Education, has for the past decade been exploring representations of slavery in children’s literature. Over the last six years, she and her research team have compiled a database of 160 children’s books covering slavery that were published between 1970 and 2015—almost half of all the children’s books on slavery published in the 35-year period, many of which are no longer in print.

An expert on children’s literature and the teaching of African-American literature, history, and culture in K-12 classrooms, Thomas says parents, teachers, and educators must consider questions of readership, ethnicity, class, gender, story, background, intended audience, and difficulty when selecting books for their students.

Thomas supports the criteria put forth by scholar Rudine Sims Bishop that children’s literature about slavery should, in part, celebrate the strengths of the black family as a cultural institution and vehicle for survival, and bear witness to African Americans’ determined struggle for freedom, equality, and dignity.

Ashley Bryan’s “Freedom Over Me: Eleven Slaves, Their Lives and Dreams Brought to Life” is a book Thomas points to as one that successfully gives an accurate depiction of slavery, humanizing African Americans held in bondage while also conveying the truth and difficulty of slave life.

“I recommend this book. What you’re getting here is 11 slaves’ lives and dreams that are being brought to life by this author,” she says. “[Bryan] is representing their complexity in the illustrations, his writing of the poetry. I highly recommend this because it balances humanizing enslaved African Americans, but he’s also showing the complexity of their lives.”

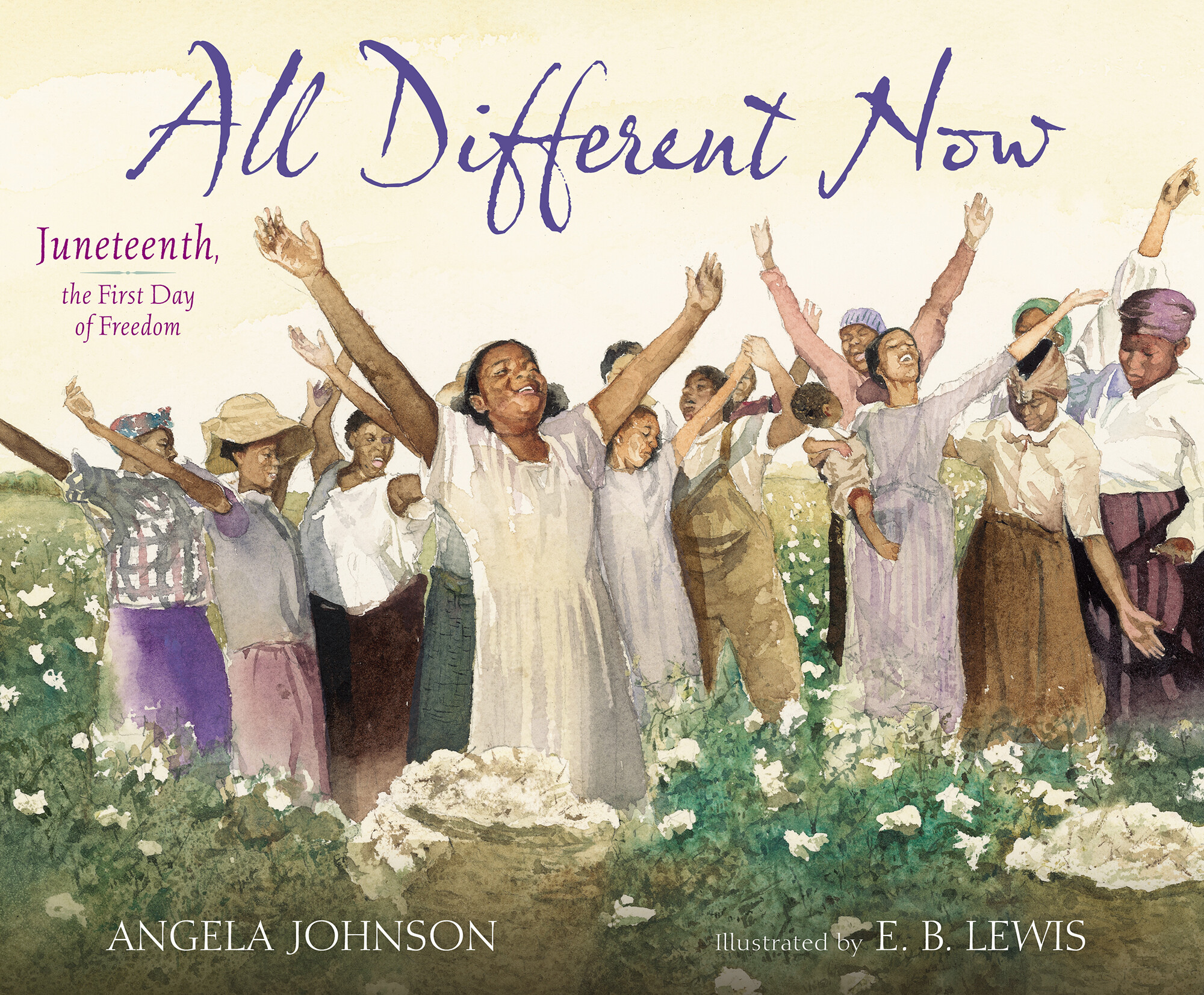

Thomas also praises “Underground: Finding the Light to Freedom” by Shane W. Evans; “All Different Now: Juneteenth, the First Day of Freedom” by Angela Johnson; “Freedom Song: The Story of Henry “Box” Brown” by Sally M. Walker; “Almost to Freedom” by Vaunda Micheaux Nelson; “The People Could Fly: The Picture Book” by Virginia Hamilton; and “Love Twelve Miles Long” by Glenda Armand.

Emily Jenkins’ picturebook “A Fine Dessert: Four Centuries, Four Families, One Delicious Treat,” was published in 2015 by Schwartz & Wade and caused a storm of controversy.

Initially well-reviewed and highly praised, the book depicts parents and children in four different centuries making a dessert called blackberry fool. In a story that takes place in 1810, an unnamed enslaved black mother and her daughter happily make blackberry fool in the kitchen on a South Carolina plantation, with nary a hint of terror, displeasure, or fear.

Months after the book was released, social media raged over its depiction of cheery and smiling slaves, and the lack of concern for how the images would be received by readers of color.

Interviewed by The New York Times, Thomas called depiction of happy slaves “degrading” and said the book suggested a misleading equivalency between the enslaved family and the other white families.

“Publishers are not thinking enough about who is reading these books,” she told the Times. “Imagine reading ‘A Fine Dessert’ to a classroom in Philadelphia that is 90 percent African-American. How are those kids going to feel?”

Jenkins, the author of the book, eventually apologized for being racially insensitive.

Ramin Ganeshram’s 2016 picturebook “A Birthday Cake for George Washington” also caused outrage after its release. It took only a few weeks after its publication for reviewers to criticize its whitewashing and depiction of smiling, joyful slaves. The book portrays Hercules, an enslaved African owned by Washington and forced to work as his chef, and his daughter gleefully making a birthday cake for the president.

Publisher Scholastic eventually pulled the book from distribution.

On top of her 160-book database on slavery in children’s literature, Thomas is conducting reader response surveys in Philadelphia public schools, and has published two articles on representations of slavery in children’s books.

Additionally, she is working on a book about slavery in children’s literature tentatively titled “Reading Racial History,” and she serves on the advisory board of Teaching Tolerance’s Teaching Hard History project.

Thomas says children’s literature is a prime site for social reproduction, and an unexamined site of social progress, regress, and/or transformation.

“If you have children’s media that’s regressive, and the children of today are going to be the adults of the mid-to-late 21st century, if we don’t change the children’s media that they’re being fed by, just like we still remember and talk about ‘Peter Pan,’ ‘Alice in Wonderland,’ and other fictions of the long-ago Victorian and Edwardian eras, they’re going to still be influenced by these current writings—from ‘Harry Potter’ to problematic books about slavery—deep into the 22nd century.”

(From left) Doctoral student Hannah Yamagata, research assistant professor Kushol Gupta, and postdoctoral fellow Marshall Padilla holding 3D-printed models of nanoparticles.

(Image: Bella Ciervo)

Jin Liu, Penn’s newest economics faculty member, specializes in international trade.

nocred

nocred

nocred