nocred

In a year that’s presented unimaginable hardships and loss for so many, Penn Today wanted to finish off 2020 by sharing heartwarming stories of Penn community members helping those in need—in their own backyards and across the world—as part of our Side Gigs for Good coverage.

This series has pulled back the curtain to reveal hidden facets of people who already spend their days doing amazing work, like a biologist who sells waffles to fund Tourette’s research or a surgeon whose band raises money to benefit gynecologic cancers. Since December 2019, eight installments have profiled more than 40 undergraduates, grad students, faculty, and staff in 28 inspiring stories featuring eight of Penn’s schools.

The stories below are no different.

They include students from the Perelman School of Medicine who provided supplies to West Philadelphia community groups; an undergraduate working to build toilets for a secondary school in The Gambia; a School of Arts & Sciences professor and a Wharton assistant professor helping homeless people in New York City; and an update from a staffer fostering a working dog.

Then there’s Sarvelia Peralta-Duran, administrative director of the Jerome Fisher Program in Management & Technology. Since June, she’s delivered food once a week to senior citizens around her neighborhood. “There’s been so much uncertainty and news about so much going wrong, so many people suffering,” she says. “I wanted to do something that had an impact on me, but that also helped my community.”

In a school in the Gambian village of Bwiam, students must walk a long distance to use the bathroom. Even after they make the trek, carrying their own water to wash up, the facilities amount to little more than a hole in the ground.

When junior Fatima Al Rashed visited Bwiam during the summer after her freshman year, part of the Penn Abroad Global Research and Internship Program, she witnessed these difficult conditions firsthand. She also noticed that they took a particular toll on girls.

“It made it very hard for a menstruating female to go to school,” Al Rashed says.

As part of her internship, she conducted a survey of 108 female students aged 15 to 21, looking into the challenges they faced during menstruation. She found they lacked access to sanitary pads and that the toilet facilities were inadequate. More than 84% of students surveyed reported missing school at least one day a month as a result.

Al Rashed, a biology major who volunteers for the Penn Medical Emergency Response Team as a certified EMT, wanted to find a way to help the students. “There’s a lot to be done,” she says, “but I thought it would make sense to start by building toilets.”

She started raising funds using a GoFundMe during the summer of 2019 and, despite the challenges of fundraising during the COVID-19 pandemic, is about halfway to the $6,400 needed to finish the project, which will involve constructing six private toilets with running water near the school’s entrance. She hopes to fully fund the effort and build the toilets in 2021, working with the organization Power Up Gambia and the Bwiam village committee.

“Having grown up in Iraq, I’m really passionate about supporting females, because I didn’t always see that happening where I’m from,” says Al Rashed, who moved to Connecticut with her immediate family when she was in high school. “I’m truly a believer that education for females is what gives them power.”

For Sarvelia Peralta-Duran, administrative director of the Jerome Fisher Program in Management & Technology, it all began with an email. “A friend of mine who lives in West Philadelphia had been volunteering for a grassroots effort that started in the initial days of the pandemic,” she says.

Back in March, Philadelphia City Councilmember Jamie Gauthier and Rick Krajewski, elected in November to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, created what they called the West Philadelphia Mutual Aid Effort. They were seeking volunteers for a number of jobs, including phone banking and food delivery.

“I felt compelled to do something,” Peralta-Duran says. “I’ve been a longtime West Philadelphia resident, since I graduated from Penn back in 2001, and this effort spoke to me because of the impact that COVID-19 was having on our predominantly African American community.” By then, she was already working from home, so she decided to dedicate her lunch hour on Fridays to the cause.

At the start of each week, she would receive notification of her route and where to pick up the food, along with contact information for her recipients. The day before dropoff, she’d call each person. “Here and there, I would see the same people,” she says. “Some were friendlier and would want to have a conversation. We would chat about how they were doing, about the election, what’s happening, have you voted. I think they just appreciated someone to talk to.”

Some offered their opinion about the food itself, too, which included frozen meals and produce boxes akin to those from a CSA. They preferred the meals to the vegetables, she recalls. “It was a lot of fresh produce and some of them were just not up for doing a lot of cooking.”

Though the program has officially wound down, Peralta-Duran is still making deliveries, with help from the coordinator who had been leading all the volunteers. At its peak, the effort provided food to more than 200 West Philadelphia seniors. About 16 or so still get the weekly deliveries, with a helping of friendship on the side.

COVID-19 can spread like wildfire when people group together inside, putting those who live in shelters at a heightened risk. To protect them, this past spring New York City offered shelters access to hotels emptied out due to the pandemic. Support staff relocated to the hotels as well, allowing shelter residents continued access to services as they gained private rooms.

A handful of these hotels were located in Manhattan’s Upper West Side, where some permanent residents quickly objected to the relocation. “It was truly awful to hear how some of the wealthiest people in the city were responding to the presence of some of the most vulnerable people in the city,” says Melissa Sanchez, the Donald T. Regan Professor of English and Comparative Literature in the School of Arts & Sciences, who lives on the Upper West Side. “In a neighborhood where people have so much and could have really helped, some were instead trying to drive the shelters out.”

To combat this outcry and instead uplift shelter residents, the Upper West Side Open Hearts Initiative emerged as a grassroots effort. Penn assistant professor Corinne Low of the Wharton School, another Upper West Side denizen, was a co-founder, and Sanchez was active from the organization’s start. Both now serve in leadership roles.

The group has forged connections with shelter caregivers and residents, fostered awareness and education around homelessness issues, and lobbied city officials to ensure unhoused people not only receive needed support, but also have a voice in decisions that affect them. For their efforts, Open Hearts received the 2020 Compassionate Community Award from the NYC Coalition for the Homeless.

Sanchez says that while she had supported efforts to combat homelessness in the past, the events of 2020 turned her into an activist—a shift she’s been heartened to see in many of her fellow faculty at Penn. “It’s such a cliché to say everyone can make a difference,” she says. “But there really are a lot of ways a single individual, as well as a collective of individuals, can influence things in concrete ways.”

Every year, the Med Student Government (MSG) of the Perelman School of Medicine (PSOM) receives an allotment of money from the University’s Graduate and Professional Student Assembly, which MSG then disseminates to 100 or so groups. The idea is to fund lunch talks and other events. But like with so many facets of 2020, the pandemic made most such happenings disappear.

“At the end of the fiscal year, the money doesn’t carry over. It’s use it or lose it,” says Michelle Rose, MSG treasurer and a second-year medical student. “So, we came up with this idea to have students submit projects that the groups with leftover money could then give to. The money wouldn’t go to waste and we could do some good for the community.”

In October, the med student body received an email explaining the situation and asking for project submissions. Rose says she and her fellow board members hoped to receive a few ideas and had a goal of redistributing $2,000. The actual response blew them away: They ended up with nine projects—eight student-led, one from the school’s administration—and about $12,000.

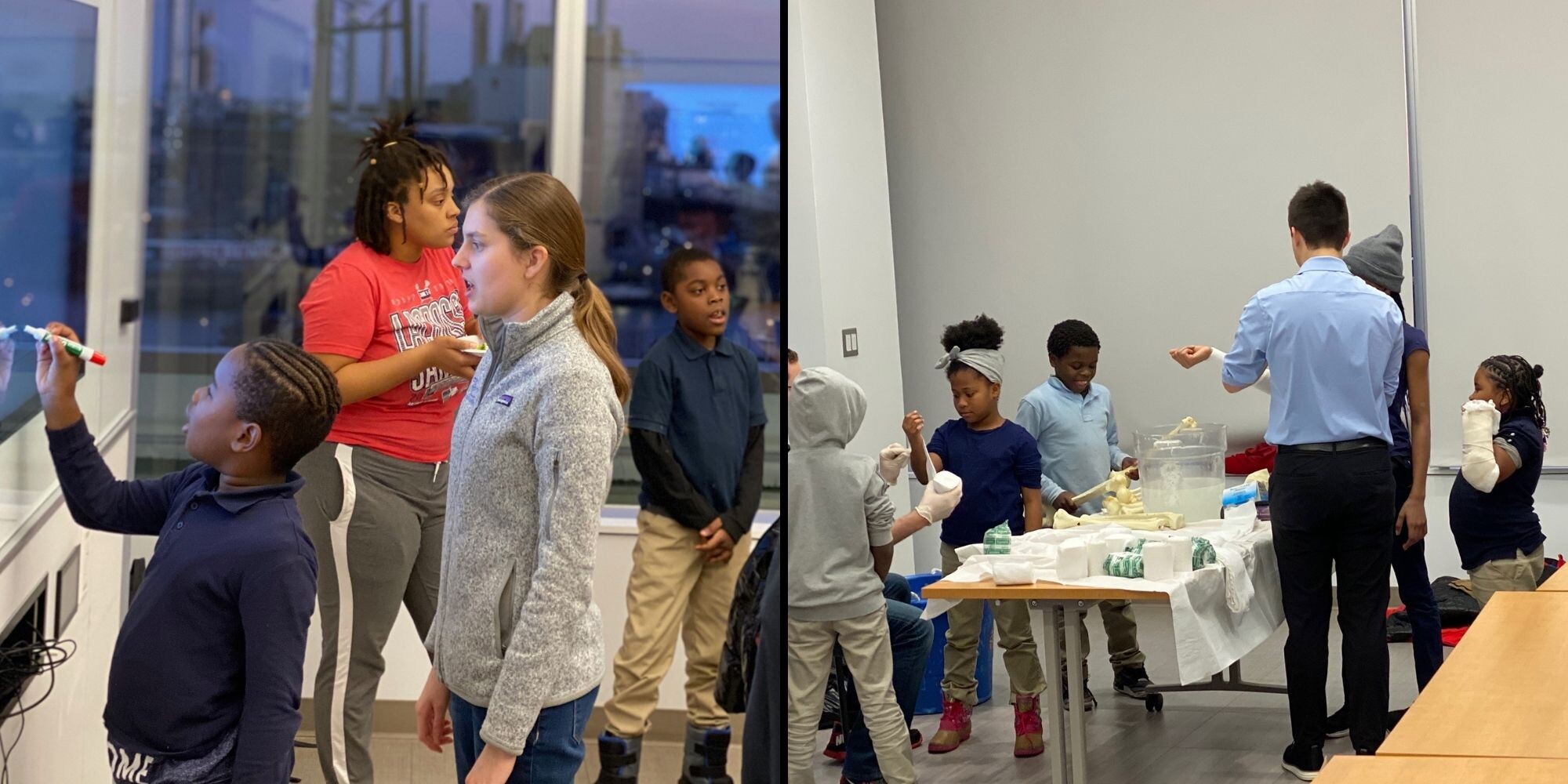

The bulk of the projects center around supplies, Rose explains. One, for example, provides funding for keyboards, backpacks, and other needs for the Benjamin B. Comegys Elementary School in West Philadelphia, where, in a typical year, a PSOM group visits weekly. Another purchases clothing for patients at the local hospitals who are known to be homeless. A third focuses on money for personal protective equipment for the community clinics where Penn medical students often volunteer.

“There were a lot of great projects,” Rose says. “We were just floored.”

“All of these projects deserved their full funding and more,” she adds. “They’re the ones making a difference in Philadelphia.” Most have already received the repurposed money and have begun putting it to good use.

A year ago, Heather Calvert and her family were just getting used to having black Labrador Ugo around. One of working dogs in training at the School of Veterinary Medicine’s Working Dog Center (WDC), Ugo was just 3 months old, wriggly and energetic. Speaking to Penn Today at that time, Calvert had noted that one of the perks of fostering for WDC was balancing having a dog and working full time, as the dogs go to “school” at the Center each day and stay home with their foster families on nights and weekends.

Just a few short months later, however, the pandemic forced the WDC—along with many University operations—to go remote.

For Calvert, executive director of MindCORE, her husband Matt Gauntt, a web developer in Human Resources, and their son, Ugo made this somewhat disorienting transition easier.

“He was a great comfort,” Calvert says. “He was really helpful to me personally by giving some stability to my day. He got me out of the house every day because he needed to be walked.”

While the Center was physically closed, from mid-March until mid-May, staff provided “online school” for the dogs, shipped food and other supplies to the fosters’ homes, used a shared Slack channel to navigate any problems, and asked foster families to take video of them going through their paces.

Calvert occasionally met up with another WDC foster family, that of Ugo’s sibling Umar, for walks in the Woodlands. Ugo will soon take on a job as a working dog, which means his time with Calvert’s family is coming to an end. And that’s a transition that won’t be easy. “We’ll absolutely miss him,” she says. “But I’m excited for him.”

This is the eighth article in a series on Side Gigs for Good. Visit the Penn Today archives to read parts one, two, three, four, five, six, and seven. If you have a side gig for good to share, COVID-related or otherwise, contact Michele Berger.

Katherine Unger Baillie , Michele W. Berger

nocred

nocred

Despite the commonality of water and ice, says Penn physicist Robert Carpick, their physical properties are remarkably unique.

(Image: mustafahacalaki via Getty Images)

Organizations like Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships foster collaborations between Penn and public schools in the West Philadelphia community.

nocred