Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

Allison Chou’s great grandfather is a renowned Chinese calligrapher, his works so popular and prolific they’re shown in temples in Taiwan. Why, then, she eventually wondered, did she not know how to write calligraphy?

“I asked my mom why I hadn’t learned Chinese calligraphy; it should be in my genes,” Chou, a May 2023 graduate and 2023-24 Fulbright Scholar, recalls. “And the reason [she gave] is that it’s because I’m left-handed and you learn Chinese calligraphy with your right hand, because of the way the strokes are structured. But as I grew up, I really wanted to learn.”

When she came to Penn and realized there were no classes or clubs for Chinese calligraphy, she saw it as an opportunity to self-teach and learn alongside others around campus. She co-founded the Penn Chinese Calligraphy Club with a fellow transfer student in 2020, but when the pandemic struck soon after, it relegated the club to online-only meetups. Still, she says, participants persevered and would creatively angle their phones and computers to their calligraphy setups. (The club mailed supplies to members for practice.)

What’s endured since is a club that’s a connective cultural tissue for Chinese and Chinese American students on campus.

The club has grown immensely from its modest pandemic iteration, welcoming about a dozen participants on Friday evenings in the ARCH Building’s fireside lounge and countless more at holiday events like the Mid-Autumn Festival. Students—undergraduates and graduates, all of whom are welcome regardless of background—gather to practice their strokes, listen to Chinese-pop or background music with traditional Chinese instruments to, Chou says, “bring out the Chinese calligraphy mindset,” and share experiences. Others, she says, view calligraphy as a meditative practice that functions as a study break from busy semesters.

Alan Han, a third-year in the School of Engineering and Applied Science, encountered the club two years ago while perusing tables at the Locust Walk Student Activities Fair. His parents, he says, used to make him practice Chinese writing, which he didn’t enjoy, so they asked if he’d try calligraphy instead. Because he had a background in sketching, he viewed it more as a drawing exercise and stuck with it.

For that reason, he jumped at the chance to join the club when he discovered it existed, mostly because he thought he’d never encounter it in the first place.

“In high school I thought, ‘That’s it, I’m in college now and an adult and I don’t need to do calligraphy because my parents won’t make me,’” Han says.

Alas, he discovered that he wanted to practice after all. And, as he does now, instruct newcomers.

The club’s current president, Regina Chau, a fourth-year in the College of Arts & Sciences from Egg Harbor Township, New Jersey, began practicing calligraphy during the pandemic, primarily because it was one of few clubs that could be conducted online. She was surprised that she enjoyed it as much as she did.

“Calligraphy, there are two reasons why I like it: The first is that it feels like good meditation, because you have to go really slow and control your breathing when your hand is shaking; and the second reason is that it has helped me connect to my family,” Chau explains. “My family from my dad’s side is from China and they haven’t seen calligraphy in years, but through this club, we have these water books where you use water instead of ink on the book and it disappears in a few minutes. So, I brought supplies to my family, and they were amazed by it. It was a nice bonding experience.”

Han says others, like himself, are surprised and intrigued to see the club exists, especially given calligraphy’s almost punitive reputation among schoolchildren.

“A lot of people have a parent or grandparent who has done Chinese calligraphy or were made to do it as elementary schoolchildren, and like me, they drop it a number of years and are shocked to find it’s a club with a decent size and following on campus,” says Han. “It’s a common story we hear. ‘My grandpa does this,’ or something like that.”

Chinese calligraphy has roots as not just an art form, but a scholarly pursuit. Jing Hu, a lecturer in the Chinese Language Program, says that while Chinese script dates to the ancient era of oracle bone inscriptions, calligraphy is largely associated with the Chinese art form that emerged during the Han Dynasty alongside Chinese paintings.

“Calligraphy played an important role in recording historical events, governmental decrees, religious texts, philosophical writings, and also scholars—intellectuals—highly regarded calligraphy as the essential skill for anyone aspiring to be part of the literati,” she says. “Knowing and mastering calligraphy was a hallmark of refined education.” Many emperors and eminent officials in Chinese history, such as Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty, Emperor Huizong of the Song Dynasty, and notable figures like Chu Suiliang, Su Shi, and Huang Tingjian, were all accomplished calligraphers.

The five scripts used in calligraphy symbolize everything from a mind-body-spirit connection to an embodiment of someone’s personality, Hu says. During some dynasties, she explains, ministers would be selected based on the quality of their calligraphy and the elements of their personality they infused into it—“‘Ren ru qi zi’ is an old Chinese saying, which functionally translates to ‘One’s calligraphy reveals one’s character,’” she says.

Even today, there are many Chinese people who see it as an important art form.

“It’s bridged the gap between the Asian tradition and modernity, and people now continue to create new styles of calligraphy while keeping the rich heritage,” Hu adds.

She was so impressed with the Chinese Calligraphy Club that she invited the group to demonstrate at a year-end celebration held in May as part of the Chinese Language Program. They’ve also engaged with classes in the Chinese Language Program.

Looking ahead, Han hopes to continue to lower the barrier to entry for learning Chinese calligraphy.

“We want to lower the stakes and the pressure of learning calligraphy, especially for the American-born Chinese people whose parents and grandparents did this,” he says. “The way I look at it, a lot of times in trying to assimilate—trying to be part of American culture or a new society—you discard or throw away a lot of your lifestyle or culture back in China, or wherever, and at the same time we get the pressure of ‘Why don’t you speak Chinese better? Why don’t you do calligraphy? How come you talk to me in English?’

“So, we really try to resolve some of that tension by saying ‘It’s OK, you don’t need to know any Chinese, and if you know a bit, great—just give it a try and we’ll teach you and hold your hand through all of it.’”

Image: Kindamorphic via Getty Images

nocred

nocred

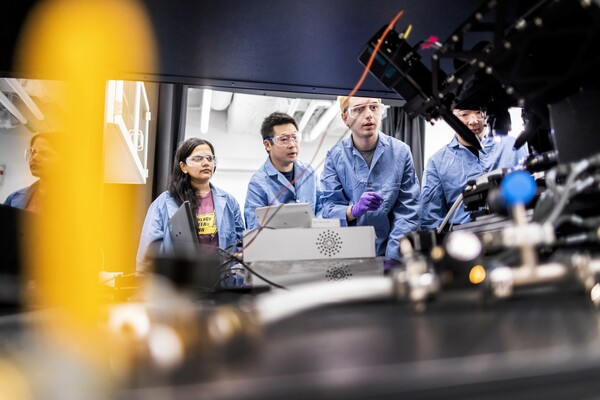

(From left) Kevin B. Mahoney, chief executive officer of the University of Pennsylvania Health System; Penn President J. Larry Jameson; Jonathan A. Epstein, dean of the Perelman School of Medicine (PSOM); and E. Michael Ostap, senior vice dean and chief scientific officer at PSOM, at the ribbon cutting at 3600 Civic Center Boulevard.

nocred