nocred

A month ago, the University-wide announcement came: Labs across campus must put on hold all nonessential on-campus research activities. Though the message was simple, the decision to come to it was anything but, says Dawn Bonnell, Penn’s Vice Provost for Research.

“It wasn’t easy to think about turning down all research except for that which was deemed to be essential,” she says. “We based the decision on evidence, on what was happening in our region, in the country, and globally. We came to understand the impact of not depopulating the research labs in terms of the health of our community. It was the right thing to do.”

Going quiet has meant different things for different labs, depending on their use of animal models and cell lines, people the lab employs, years it’s been running, even experience level of the principal investigator (PI). For some at Penn, this change has been as straightforward as it could be given the strange circumstances. For others, it has posed complicated challenges that involve determining what’s crucial to maintain versus what’s OK to let go.

Unquestionably, for everyone, this has presented a challenge that researchers have never before faced.

“I’ve had a lab for 20 years. I’m not sure we’ve ever had a time where nobody was doing an experiment for more than a week,” says molecular biologist Boris Striepen of the School of Veterinary Medicine. “Even when we shut down over the holiday break, not everybody stops working. Having a lab is a little like a farm; you cannot shut down the farm. It’s a living thing.”

And yet, Striepen’s lab and so many others across campus have come up with creative ways to remain productive and keep in touch, with focused writing and virtual coffee breaks. They’re putting together grant proposals and manuscripts, review papers and dissertation intros. Federal agencies, directed by the Office of Management and Budget, have loosened the grip on funding requirements and said they might consider proposal extensions, relieving some of the productivity pressure on labs and scientists.

“If this had happened 10 or 15 years ago it would have been possible but not easy. We have the technology to do this now, and we’re a community that has the skillset to make this work,” Bonnell says. “Everyone wants to continue to be as productive as they can.”

In the world of research, there’s a distinction between wet and dry labs. In the former, scientists conduct bench work, working with cells or animal models in biological research, or with specialized equipment and materials in fields like chemistry and physics. Experiments often involve a model system that’s altered in some way, then compared to a control group. Research in dry labs, on the other hand, typically happens computationally, with scientists parsing massive datasets to seek out patterns.

These are generalizations, of course, with much more crossover and nuance than the description above allows. But understanding that these two broad categories exist provides some context for how labs across Penn, like that of biologist David Roos, had to react when asked to temporarily shutter.

Roos ran an active wet lab for 30 years studying parasites, evolutionary cell biology, and host-pathogen interactions. With the rise of genome sciences, his work has become increasingly computational, helping researchers around the world to capture, manage, and mine large-scale datasets. His group is now entirely computational, which meant a relatively seamless transition to remote working.

“Our team is dispersed around the globe, with staff at several sites in the U.S. and UK, as well as in Germany, Brazil, and Uganda,” he says. “Even before the coronavirus pandemic, we were already conducting much of our business via conference calls and were pretty adept at the available technologies for online chatting, video conferencing, screen-sharing, and cloud-based collaborative work.” As a result, the lab has been able to keep moving apace with its research, providing resources to scientists now unable to work at the bench, he adds.

Other labs however, like those run by chemist Thomas Mallouk or physician-scientist Daniel Kelly, had to halt experiments altogether.

Mallouk’s lab synthesizes new nanoscale materials and then analyzes their potential in energy-conversion technologies. “One big focus of the group is how we convert electrical energy into chemical energy and back,” says Mallouk, the Vagelos Professor in Energy Research in the School of Arts & Sciences. “We have to make molecules and fabricate electrodes. It really requires a laboratory.”

The same holds for Kelly, the Willard and Rhoda Ware Professor of Medicine who also runs Penn Medicine’s Cardiovascular Institute. His lab studies muscle metabolism—how muscle cells work—and what happens when the heart becomes “energy starved.” His research program involves studying heart failure in dozens of unique genetic animal models and using hundreds of unique cell lines.

If this had happened 10 or 15 years ago it would have been possible but not easy. We have the technology to do this now.

Dawn Bonnell, Penn’s Vice Provost for Research

Unlike Mallouk and other researchers whose labs don’t require constant upkeep, who can likely pick up where they left off when this ends, Kelly and PIs with similar labs face an additional hurdle: keeping crucial animals alive, cell lines viable, reagents frozen, and liquid nitrogen stocked. At the outset of these changes, that meant significant mental and operational shifts.

“Initially, this was hard for everyone to get their heads around because we are talking about scientists who spend day and night in the laboratories. It’s really not just a job,” Kelly explains. “At first, we thought maybe we could work in shifts. But if you get right down to it, the number of people, the potential ‘germ pools’ in the building, need to be whittled way down. We had to adapt to the new reality that we could no longer operate in a business-as-usual manner.”

Rather, extraordinary circumstances require extraordinary measures: Some labs froze mouse embryos, which still means they’ll lose time when they breed the animals again, but far less time than if those genetic models had been lost altogether. Labs also appointed a small number of essential personnel to care for and maintain small animal colonies and check on operational safety issues.

Many teams, like those in the lab of physicist Marija Drndic, are still figuring out a path forward. “We’re doing a lot of work by email,” says Drndic, the Fay R. and Eugene L. Langberg Professor of Physics in the School of Arts and Sciences. “We need a plan B for two independent study undergrad students who were working in the lab. The rest of the group—grad students, postdocs, several more undergrads who were doing research—are all on standby, like fish out of water doing parts of the work that do not require physically being in lab.”

Logistics aside, the process can be heartbreaking. “We had an experiment set up to test a hypothesis that’s dear to us and crucial to the prevention of the infection we study. We worked for the last three years to come up with technology to test this, and we were finally ready,” says Vet researcher Striepen, whose lab studies the parasite Cryptosporidium, a leading cause of diarrheal disease in young children. “We had to put that on ice for an unclear amount of time. The students and postdocs who worked so hard on this may not see the result prior to graduation.”

Stories like this will likely become common as the time away from labs extends and as the situation evolves. In the meantime, researchers are making do. Almost everyone interviewed for this piece mentioned taking advantage of the time to write—new grants and grant renewals, analysis papers and review papers and literature study. One mentioned writing a textbook chapter revision.

“We’re knuckling down, taking out our lab notebooks, and writing papers that we’ll submit for publication. We’re at the front end of that,” Mallouk says. “Students who are nearing the end of their study are writing their theses. Some who are kind of in between, second or third years who have passed their qualifying exams, I’ve encouraged them to think about drafting a review article that pertains to their topic. That’s also potentially something we could publish.”

Beyond the writing, groups are learning how to conduct lab business and educational activities virtually. “Through videoconferencing, we can stay in touch quite a bit,” Kelly says. “We have weekly, if not more frequent, lab meetings, where one of our trainees presents. We’ve added a journal club once a week, where someone identifies a paper in their area and will review it for everybody. Two to three times per week, we’re having some type of academic exercise as a group.”

Though the conference video chats can help keep the labs running, they can’t foster the same social connections that come from seeing each other face to face every day.

A new staff member started in the Roos group just as the University asked on-site work to cease. To get her set up, all they could do was pass a laptop through the open window of her car. Though videoconferencing tools have at least made it possible to welcome this new group member and get her up to speed, it’s unclear when she’ll have the chance to sit in the same room with her new colleagues.

Partially for this reason, Roos has set up regular 30-minute social video calls, so the team can chat about nonwork issues. “Our second-most recent hire works in Liverpool. She has small kids around the same age as our newest employee,” Roos says. “And we have staff in Uganda with kids around the same age, too. These people have never met in person, but they’ve met for work and socially online, and we’ve talked about creating an opportunity for their kids to meet, too.”

The Kelly lab and others in the Cardiovascular Institute have instituted virtual coffee breaks. “We take for granted what we do each day when we go into work. All of our hallway discussions have been lost,” he says. “These interactions are invaluable for our research, but perhaps even more for fostering collegial interactions and team building.”

Losing these ties, even temporarily, worries Mallouk. “This group is like a family. Everyone understands that we have to self-isolate to stay healthy,” he says. “But everyone is missing the interactions we had with each other.”

No one knows yet when the situation will shift, when labs will physically reopen and research teams will be allowed to return. For scientists, whose work focuses on answering the as yet unanswered, those unknowns can be particularly challenging.

“Everyone wants to know what’s coming and to have a plan. But we are not at a time when that can happen,” Kelly says. “We are maintaining some degree of normalcy by having frequent videoconferences—we’re all in the same boat and are still talking about science, including how we can help in understanding and treating COVID19—and that’s really helpful for the staff, trainees, and PIs. It also allows us to identify folks who are struggling. They shouldn’t be left to do it alone.”

That’s just the point: Despite physical distance from labs and team members, no one is doing this alone. Across the Penn community, researchers are proving this by staying connected and staying the course.

Dawn Bonnell is the Vice Provost for Research at the University of Pennsylvania.

Marija Drndic is the Fay R. and Eugene L. Langberg Professor of Physics in the Department of Physics and Astronomy in the School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania.

Daniel Kelly is the Willard and Rhoda Ware Professor of Medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine and director of the Cardiovascular Institute at the University of Pennsylvania.

Thomas Mallouk is the Vagelos Professor in Energy Research and a professor of chemistry in the Department of Chemistry in the School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania.

David Roos is the E. Otis Kendall Professor of Biology in the Department of Biology in the School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania.

Boris Striepen is a professor of microbiology and immunology in the Department of Pathobiology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine.

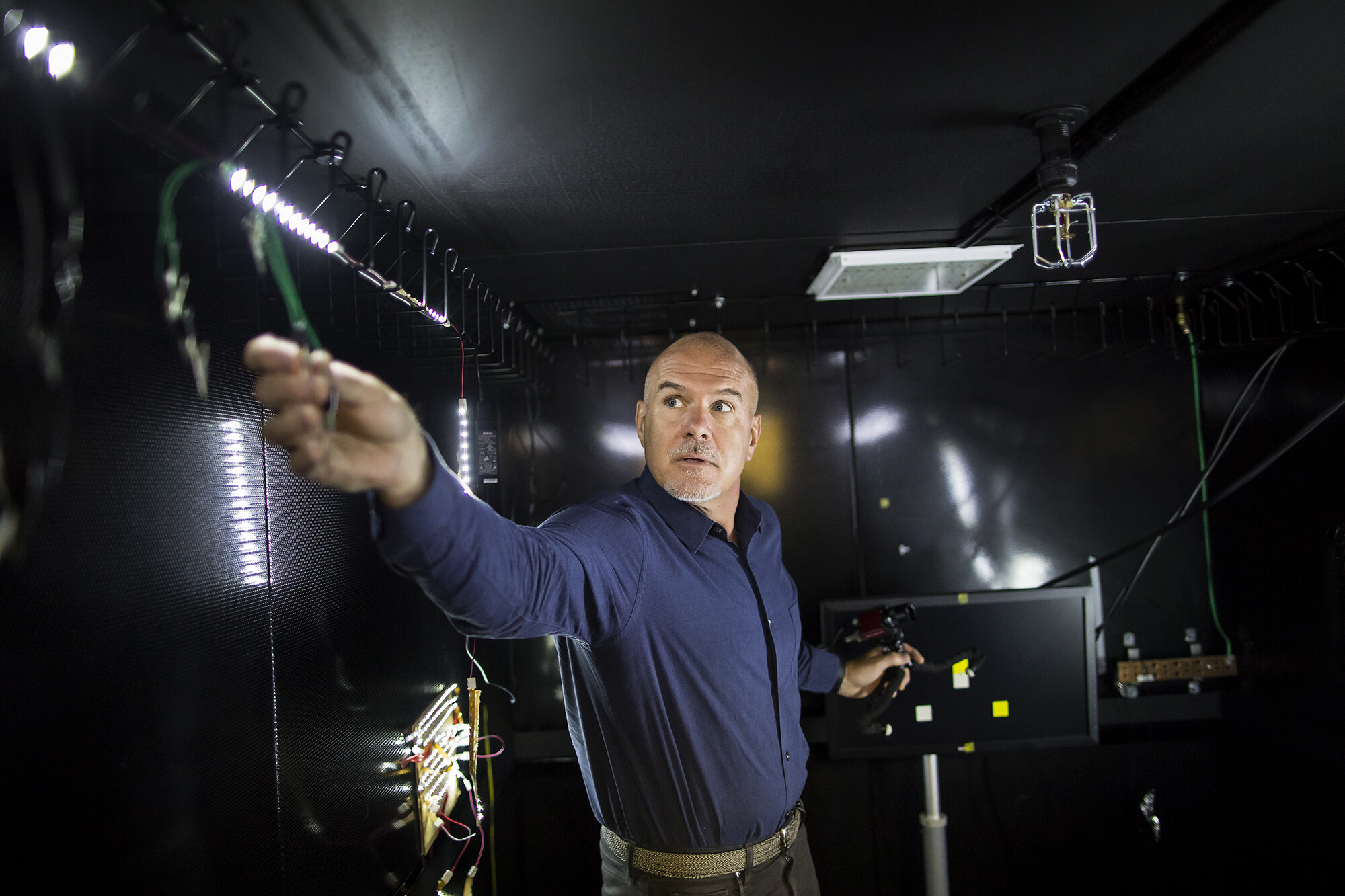

Homepage image: Luis De Jesus Baez, a provost postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Thomas Mallouk in the Department of Chemistry, in August 2019. His work focuses on unique aspects of 2-D materials and how their properties can be tuned.

Michele W. Berger

nocred

nocred

Despite the commonality of water and ice, says Penn physicist Robert Carpick, their physical properties are remarkably unique.

(Image: mustafahacalaki via Getty Images)

Organizations like Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships foster collaborations between Penn and public schools in the West Philadelphia community.

nocred