Image: Aditya Irawan/NurPhoto via AP Images

Fossil fuel powered the making of the modern world. As the first fossil-fuel state, Pennsylvania ushered the United States into the current energy-intensive economy.

“In the opening stages of the fossil fuel world we live in now, it was all about Pennsylvania,” says historian Jared Farmer. “The original oil boom in the world was here; the high-quality anthracite that was the best fuel source of the 19th century was almost exclusively in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania has a kind of planetary importance.”

The state’s role in laying the groundwork for our current climate crisis inspired Farmer to make his first class at Penn a seminar called Petrosylvania, which he describes as a historical accounting and an ethical reckoning of coal, oil, and natural gas.

Over the fall semester, students investigated the histories and legacies of fossil fuel in the Commonwealth, in Philadelphia, and at Penn, contributing to a multi-year research project that will eventually be available to the public. Students did original research, mostly online, using historical databases as well the University Archives & Records Center.

Farmer also had a personal reason for wanting to delve into these histories of Pennsylvania and Philadelphia: He’s in the midst of his first year of teaching at Penn and living in the city.

“I’m very much a place-based historian,” he says. “I like to write about and learn about and teach about where I’m living.”

I want to reach students outside of history as well as in history, and do something that’s timely and ethical.

History Professor Jared Farmer

Originally from Utah and trained as a historian of the 19th-century American West, he earned his undergraduate degree from Utah State, his master’s from the University of Montana and his Ph.D. from Stanford. He’s written books exploring various western regions, like the Colorado Plateau in “Glen Canyon Dammed,” the Great Basin—including his hometown in Utah—in “On Zion’s Mount,” and about California in “Trees in Paradise.” He most recently taught at the State University of New York at Stony Brook.

“I got this amazing opportunity to come to Penn,” Farmer says, and he used his beginner’s knowledge of mid-Atlantic history as motivation. “I want to know more about where I live, I want to know about the history of the University that now employs me, the state where I now live,” he says. “I want to connect with all the scholars on campus doing climate and environmental research. I want to reach students outside of history as well as in history, and do something that’s timely and ethical.”

The creation of the Petrosylvania course let him and his students achieve that and more.

The research was split into three parts: the Schuylkill River watershed, which Farmer calls America’s original petrochemical corridor; oil refineries in Greater Philadelphia, including their labor and environmental impacts; and the University itself, including when it started or stopped teaching certain courses like mining, polymer chemistry, and energy policy. Students were paired with topics that interested them.

Nikita Patel, a freshman in the School of Nursing from Lexington, Kentucky, says she tailored her research in the class to look at air pollution because she wanted to tie her work back into public health.

She says she loved Farmer’s flexibility and support as an instructor that allowed her to gain a better understanding of historical research and feel a connection to Philadelphia, especially since she spent her first fall semester far from the city and University.

“I’d only been to Philadelphia once before the pandemic hit, so this was a cool way to connect to the city and to campus as well as take a specialized approach to environmental studies,” she says.

Georgia Ray, a senior from Denver studying urban studies, cognitive science, and philosophy, says she was looking for a class focusing on how environmentalism is happening in cities.

“This class was a perfect combination of my interests of urban studies and environmentalism,” says Ray, who is also a student fellow at the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy.

Ray says she wanted to use the opportunity look at fossil fuels from a foundational perspective, from 1875 to 1975.

“Why do some people think they’re bad? Why do some people champion them? This class has done an awesome job allowing me to form my own beliefs on the issue and I think that's so valuable for anybody,” she says.

A guest speaker, Bilal Motley, who worked at the now-shuttered Philadelphia Energy Solutions (PES) plant, and who was there during the explosion in 2019, helped give a human perspective to the industry, she says.

“The biggest takeaway I've had from this class is how the issue is not black and white,” she says. “I personally have come away realizing the nuance of this issue and how there are so many players involved. It’s really important to consider what it means to move away from fossil fuels and what we need to do to help everyone involved when we're doing that.”

This spring, Ray will continue working with Farmer as a Public Research Intern sponsored by the Penn Program in Environmental Humanities.

Sage Basri, an environmental studies sophomore from Rumson, New Jersey, heard about the Petrosylvania course over the summer when she was working with Franca Trubiano from the Weitzman School of Design on research that connects social and environmental justice with human health and architecture. That work focused on studying the impacts of the PES refinery and was to be a starting point for empowering community members and the building industry to better understand the long-lasting legacies and wide-ranging impacts of petroleum on the built environment.

Basri, who has an award-winning policy essay coming out through the Kleinman Center soon, focused her Petrosylvania class research on a deep dive into Penn’s curriculum, to see how the University has taught fossil fuels over time.

“I loved learning these historical research methods. Archival research is far different than what I was doing this summer, which was more investigating the internet as a whole library in itself. Now, I’m looking through Penn’s catalogs from the 1860s to 1900.”

She says it’s been fascinating to see how Penn has taught energy over time.

“I feel like sustainability is a buzzword. It’s very trendy now and we almost think that people didn’t notice the environment before today, but that’s just not the case,” says Basri, who, like Ray, is a Kleinman undergraduate fellow.

Her largest contribution to the project is going to be a timeline highlighting dates when certain subject and topics—like mining and metallurgy—were introduced in the curriculum and when they dropped off.

“I’m really excited to see where the research project goes and to see the end product,” she says.

Farmer plans to teach the course two more times, in fall 2021 and fall 2022. The work of each student cohort will build on the last. In addition, he has hired a part-time researcher, Ph.D. candidate Chelsea Chamberlain, and he hopes to supervise summer interns through the Center for Undergraduate Research and Fellowships. All of this research—including thousands of documents he has collected himself—are being organized in a cloud-based archive hosted by Box. At the end of this collaborative effort, there will be a website to showcase student projects, as well as an executive report Farmer will write and present to the University.

He says he hopes the course helps the three cohorts become better researchers and scholars and helps them become better informed about the place where they lived for a formative period and the school they’re connected to for the rest of their lives.

“I want them to feel that this is part of a longer history of which they are now also a part: the history of Penn,” he says.

The biggest takeaway I've had from this class is how the issue is not black and white.

Senior Georgia Ray

Farmer sees the research as a complement to the Penn and Slavery Project, which investigated Penn’s connections to slavery and scientific racism, as well as an extension of PPEH’s “Futures Beyond Refining.”

“I’m hoping in the long run, whatever the students find, our colleagues throughout the University will see that Penn has an ethical imperative as one of the leading schools in the world to do as much as possible in terms of climate and environment, but also to look at its own history and to see what it has done well and what it hasn’t done well, and to see to what extent it’s implicated or tied up in the very problems it’s trying to solve,” he says.

“There are so many great scholars here on campus interested in these issues; Penn is really well positioned to be a world leader.”

Jared Farmer is a professor of history and chair of graduate studies in the Department of History in the School of Arts & Sciences.

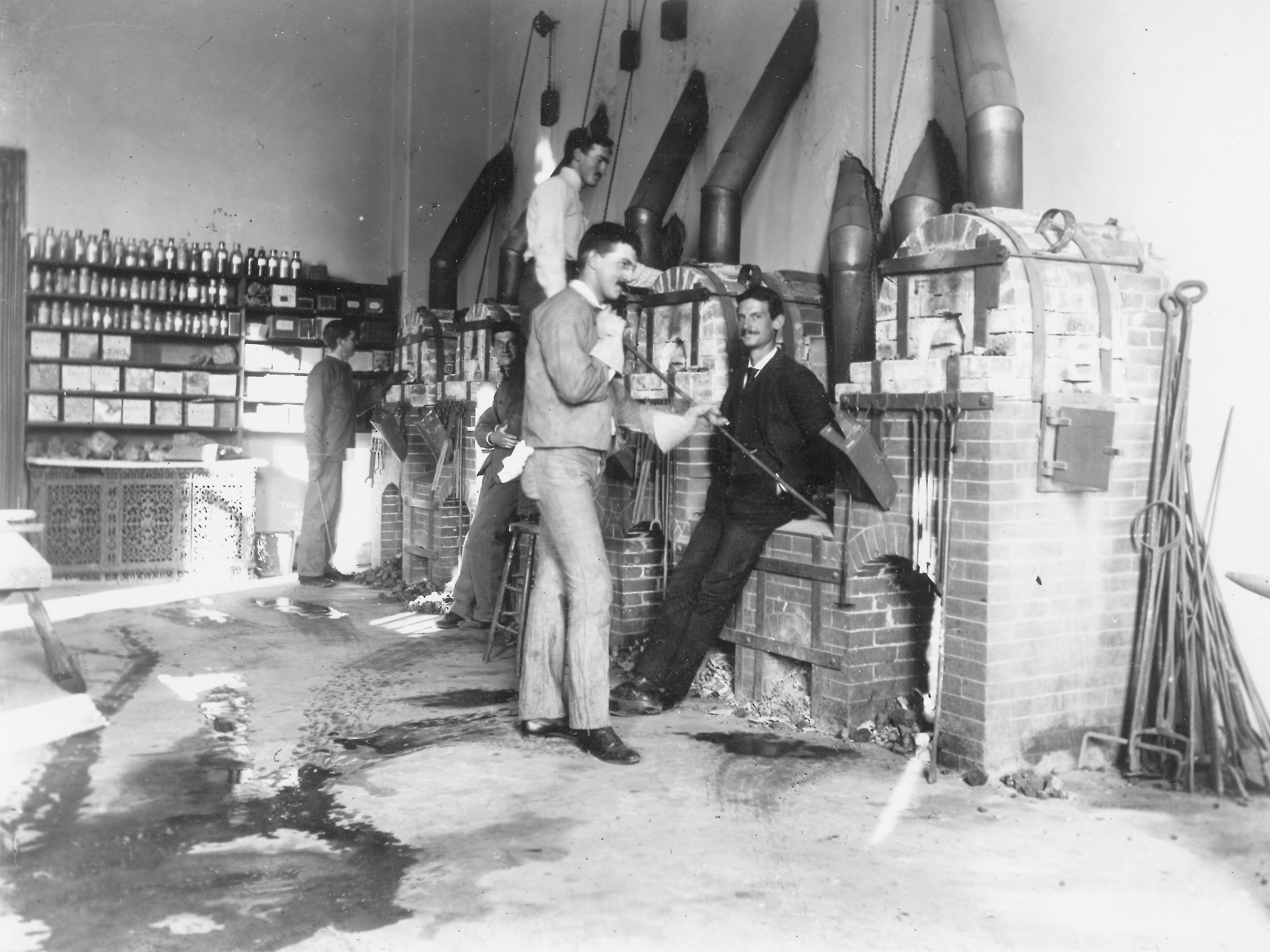

Homepage image: Campus power station at Spruce and 34th Streets (current location of Irvine Auditorium), circa 1901.

Kristen de Groot

Image: Aditya Irawan/NurPhoto via AP Images

nocred

Image: Michael Levine

A West Philadelphia High School student practices the drum as part of a July summer program in partnership with the Netter Center for Community Partnerships and nonprofit Musicopia.

nocred