Griffin Pitt, right, works with two other student researchers to test the conductivity, total dissolved solids, salinity, and temperature of water below a sand dam in Kenya.

(Image: Courtesy of Griffin Pitt)

Penn played its largest role yet in this year’s United Nations climate change conference, COP27. The conference, held in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, from Nov. 6-20, and attended by more than 30,000 people, included policy discussions, climate events, and negotiations that resulted in a deal to fund “loss and damage” related to climate change. In its third year with accredited observer status, the Penn delegation contributed to both the negotiations at the center of the conference, including significant work on loss and damage conversations, and the series of events at its perimeter, called the “blue zone.”

“Penn has real expertise on climate solutions, so it’s really important for us to participate in these international venues where finding solutions is the number one priority,” says Cornelia Colijn, executive director of the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy and one of two heads of Penn’s delegation, with Michael Weisberg, the Bess W. Heyman President’s Distinguished Professor in the Department of Philosophy.

More than 30 representatives from across the University—including the Kleinman Center, Perry World House (PWH), School of Arts & Sciences, Penn Carey Law School, School of Veterinary Medicine, Stuart Weitzman School of Design, Penn Institute for Urban Research (Penn IUR), and more—participated in COP27.

“Penn is an international leader in the fight against climate change,” says President Liz Magill. “Focused research and teaching on all issues related to climate is a top institutional priority across the University, and it’s a testament to our broad expertise on climate change that so many from Penn could share their knowledge and insights in front of an international audience of this caliber. This type of engagement is crucial to finding solutions to one of the biggest challenges we face today.”

Shortly after the conclusion of COP27, Magill and Penn Board of Trustees Chair Scott L. Bok published a statement—which will also run in the Dec. 6 issue of the Almanac—articulating how Penn is responding to the challenge of climate change in its management of the endowment (see the sidebar). The University has also launched a new website designed to centrally curate its work on sustainability in the hope of making it easier for the University community to follow Penn’s efforts to combine its research, educational, operational, and investment initiatives aimed at addressing climate change.

Overall, the 27th Conference of Parties brought together nearly 200 nations that had signed on to the 1992 U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Paris Climate Agreement was adopted at COP21 in 2015, when nearly every country in the world agreed to curb emissions to prevent global warming from surpassing 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, the temperature at which dangerous climate “tipping points” become increasingly likely. Since then, the annual conferences have focused on enacting policies and measuring progress to keep warming under that level, as well as taking actions that protect humans and ecosystems as the planet warms.

This year, the three major objectives of the 2015 Paris Agreement guided the talks: adaptation, mitigation, and financing. Adaptation addresses how countries will adjust to the unavoidable effects of climate change. Mitigation concerns how countries will moderate their emissions to prevent further warming. Financing addresses who will pay for these efforts.

The agreement surrounding loss and damage is a significant win, says Scott Moore, director of China programs and strategic initiatives at Penn Global. “This is the biggest thing to happen in international climate diplomacy since Paris—by a mile,” he says. “I don’t think many saw it coming.”

While global events like this often spotlight political leaders, nongovernmental organizations and research institutions like Penn also play a key role in sharing knowledge and lending legitimacy to the negotiations, says Weisberg, who is also director of postgraduate programs at PWH. “One thing of great importance that university researchers can do,” he adds, “is to be there at the right moment to offer their expertise to the governments and civil society organizations trying to solve the climate crisis.”

Despite efforts to limit emissions, increased incidence of droughts, wildfires, floods, and extreme weather events around the world show that the effects of climate change are here and unavoidable. This reality made adaptation one of the most pressing issues at this year’s COP and stoked an urgent need for solutions, says Melissa Brown Goodall, senior director of the Environmental Innovations Initiative in Penn’s Office of the Provost.

Adaptation strategies won’t look the same around the world, and they’ll require specific expertise to tailor them to each environment and circumstances. “The adaptation narrative is particularly important to Penn,” Goodall says, because multiple centers at the University focus on adaptation research.

For instance, climate change threatens global food supply chains, requiring a holistic solution that considers the welfare of animals, people, and the environment to prevent future food shortages. That was the subject of an address by Andrew Hoffman, the Gilbert S. Kahn Dean of Veterinary Medicine at Penn Vet, at the Nairobi Work Programme Focal Point Forum, which focused on agricultural adaptation and food security.

We’re taking our research and bringing it to bear on what’s happening within the venue. But we’re also learning while we’re there and bringing those new ideas and relationships back onto campus.

Cornelia Colijn, executive director of the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy and one of two heads of Penn’s delegation

Specifically, it provided an opportunity for researchers and delegates to interface and discuss how countries will ensure their food systems remain resilient in the face of a changing climate. Under Hoffman’s leadership, Penn Vet opened its Center for Stewardship Agriculture and Food Security earlier this month, a research hub for issues of agricultural adaptation that aims to promote responsible use of natural resources in agriculture.

Eugenie Birch, the Lawrence C. Nussdorf Professor of Urban Research in the Weitzman School and co-director of Penn IUR, joined the launch of several campaigns on urban adaptation. One, called “Roofs Over Our Heads,” is an effort to publicize and address the needs of informal settlements, led by PWH visiting fellow Sheela Patel. Another looks at ways to finance projects to beat urban heat; visiting scholar and former mayor of Quito, Ecuador, Mauricio Rodas, who is now affiliated with the Kleinman Center, PWH, and Penn IUR, is a key leader on this work.

Other engagements of Birch’s included those focused on integrated urban development in 20 cities, resilient food initiatives, technology transfer, and urban resilience. Beyond that, she attended the first COP urban ministerial meeting as a partner and stakeholder for a project called “Sustainable Urban Resilience for the Next Generation” and participated in a process that summarizes for lawmakers the highly technical Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) findings.

“They translated those findings into this simple, hopeful message: ‘Cities are hotspots of global climate emissions and risk, but they are also hubs for innovation, action, and resilience,’” Birch explains. “It’s up to us to plan and implement climate-resilient cities around the world.”

Dealing with climate change isn’t just about adapting to a new world; there are still ways to mitigate the problems that emerge in a warmer planet and to thwart further warming. The latest IPCC report states that to prevent global warming from reaching dangerous levels, countries need to cut their emissions in half by the end of 2030 and implement sustainable alternatives. At COP27, Colijn shared the Kleinman Center’s research on climate mitigation with global decision-makers.

Every year, the Kleinman Center releases policy digests on climate issues from renewable energy sources for water-stressed regions to the influence of the Inflation Reduction Act on mining rare earth elements, the minerals used to produce wind turbines and electric vehicles. Through the conference, the center has had the chance to “connect those policy digests to people who can use them,” Colijn says.

Sharing tools like these, which include policy suggestions and outcomes, at a place like COP is essential to accomplishing the Kleinman Center’s mission of a just energy transition, she adds. “COP really acts as a platform for deepening our policy engagement in this multilateral space.”

Without financial backing, conversations around mitigation and adaptation are sure to stall, Weisberg says. “To have any hope of keeping global warming below 1.5°C, the entire global economy will have to realign with the goals of the Paris Agreement,” he says. Developed countries set a target of $100 billion in climate financing every year from 2020 to 2025; at COP27, one big aim was to close the existing gap in funding arrangements, as the world has not yet mobilized that funding.

For the first time in the history of Penn’s COP involvement, Penn students got to join the delegation on the ground. This semester, William Burke-White, a professor at Penn Carey Law and the inaugural director of PWH, co-taught a course on subnational climate adaptation finance with Rodas. The professors brought 10 students to Egypt to observe the finance negotiations in real time.

“There is nowhere better to be these two weeks if you want to learn about climate change than in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt,” says Burke-White. “It’s at the heart of the action.”

The law students spent their semester studying how subnational actors—cities and states—receive climate financing after the U.N. negotiations distribute funds to countries. During the second week of the conference, they observed negotiations and developed a white paper to inform future finance negotiations. They are also each writing blog posts that will appear on the Kleinman Center site.

Hannah Sachs, a graduate student earning a joint JD and Master in Social Policy from Penn’s School of Social Policy & Practice, co-wrote one about private finance for the world’s most vulnerable cities. Sachs says traveling to COP27 offered an unparalleled learning experience: “Attending COP in person allows a much more in-depth understanding of both the substance and dynamics of the negotiations.”

Even with the efforts to adjust to climate change impacts, some of its effects are unavoidable. Colijn says one of the biggest issues at COP this year was the topic of loss and damage, which refers to the financial burdens caused by extreme and irreversible climate change circumstances. This issue of financial arrangements for addressing loss and damage isn’t a new one, but this was the first time it appeared on the agenda as a formal negotiating topic.

In an episode of its podcast “Energy Policy Now,” the Kleinman Center covered loss and damage at COP27, one of a series of audio dispatches produced to highlight the conference. Podcast host Andy Stone and PWH Lightning Scholar Stacy-ann Robinson discussed why loss and damage is such a critical matter, especially for small island states ill-equipped to financially recover from the destruction of extreme weather events.

The Republic of Maldives is one island nation vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Weisberg and Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, a PWH Professor of Practice of Law and Human Rights, joined the delegation for the Maldives, assisting during its negotiations and providing high-level policy advice and strategy.

“Michael and Zeid have provided invaluable support to the Maldives climate team since COP26,” says Aminath Shauna, Maldives’ Minister of Environment, Climate Change, and Technology. “Their technical guidance and knowledge, drawn from their vast experience in the fields of politics and international multilateral systems, helped us enormously.”

Two days after the conference was originally supposed to end, the parties at COP 27 reached an agreement—what’s been described as a “landmark deal”—on loss and damage. It establishes funding for particularly vulnerable developing countries to aid in their response to global warming’s biggest challenges. Many of the agreement’s details will get firmed up in the months to come, including which countries will finance this and which will benefit from it.

Though the U.N. climate change conference has concluded, the conversations that took place during those two weeks will influence Penn for the entire year to come.

“COP is a process and an event—but the work doesn’t just happen in two weeks,” Weisberg says. The priorities countries raise at COP27 will continue to guide research directions at Penn, he adds, and the relationships built in Egypt will form the foundation for future climate negotiations.

“The transfer of knowledge goes both ways,” Colijn adds. “We’re taking our research and bringing it to bear on what’s happening within the venue. But we’re also learning while we’re there and bringing those new ideas and relationships back onto campus.”

Representatives from Penn at COP27 included the following:

From the School of Arts & Sciences: Michael Weisberg, the Bess W. Heyman President’s Distinguished Professor in the Department of Philosophy, and Santiago Cunial, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Political Science.

From the Penn Carey Law School: professor William Burke-White; Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, Perry World House Professor of Practice of Law and Human Rights; and JD and LLM candidates Cecelia Coffey, Paul-Angelo dell’Isola, Alara Hanci, Mostafa El-Harazi, Noor Irshaidat, Sage Lincoln, Hannah Sachs, Johan Stagstrup, Alexan Stulc, and Samuel Wong.

From the Stuart Weitzman School of Design: Eugenie Birch, the Lawrence C. Nussdorf Chair of Urban Research, and assistant professor Allison Lassiter.

From the School of Veterinary Medicine: Dean Andrew Hoffman.

From the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy: executive director Cornelia Colijn; Andy Stone, host of the “Energy Policy Now” podcast; and Kimberle Szczurowski, administrative assistant.

From Perry World House: Lauren Anderson, Global Shifts program manager; Stacy-ann Robinson, Lightning Scholar; and visiting fellows Sheela Patel, Kotchakorn Voraakhom, Koko Warner, Elizabeth Yee, and Zinta Zommers.

From the Penn Institute for Urban Research: managing director Amy Montgomery; and Mauricio Rodas, former mayor of Quito, Ecuador.

From the Environmental Innovations Initiative: senior director Melissa Brown Goodall.

From Penn Global: Scott Moore, director of China programs and strategic initiatives.

From the College of Liberal & Professional Studies: Steven Finn.

Marilyn Perkins , Michele W. Berger

Michele W. Berger

Griffin Pitt, right, works with two other student researchers to test the conductivity, total dissolved solids, salinity, and temperature of water below a sand dam in Kenya.

(Image: Courtesy of Griffin Pitt)

Image: Andriy Onufriyenko via Getty Images

nocred

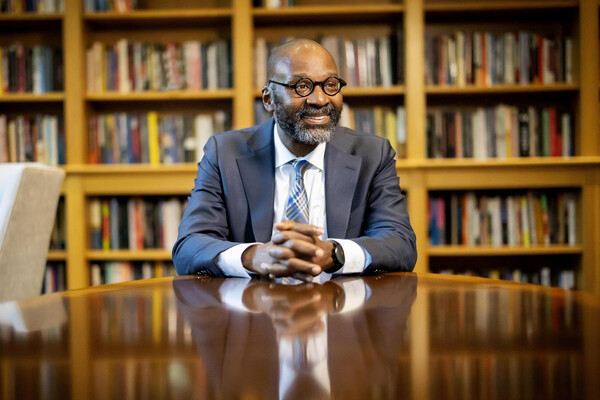

Provost John L. Jackson Jr.

nocred